[Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

Good morning,

In Meltdown, Chris Clearfield and Andras Tilcsik point to how some of the technological advances have also made the world a more dangerous place.

They write, “In the past half century, humanity has pushed its technological boundaries. We’ve harnessed nuclear power, drilled miles into the earth to extract oil, and developed a global financial system. These systems give us tremendous capabilities. But they also move us into the danger zone, and when they fail, they can kill people, devastate the environment, and destabilize economies. It’s not that we’re less safe on a daily basis; it’s that we’re more vulnerable to unexpected system failures.”

Take for example driverless cars. “They will almost certainly be safer than human drivers. They’ll eliminate accidents due to fatigued, distracted, and drunk driving. And if they’re well engineered, they won’t make the silly mistakes that we make, like changing lanes while another car is in our blind spot. At the same time, they’ll be susceptible to meltdowns—brought on by hackers or by interactions in the system that engineers didn’t anticipate.”

There are solutions. “Use structured tools when you face a tough decision. Learn from small failures to avoid big ones. Build diverse teams and listen to sceptics. And create systems with transparency and plenty of slack.

“Yet many of these ideas are rarely used in practice—even in the face of our greatest challenges. We celebrate intuition in wicked environments. We ignore voices of concern and fail to act on warning signs about climate change, famines, and imminent terrorist attacks. Homogeneous teams run some of our most important financial institutions, government agencies, and military organizations.”

The book was published a few years before coronavirus turned the world topsy turvy, and taught some of the same lessons at a far bigger cost.

In this issue

- Amartya Sen on bicycles

- The anatomy of social media

- Internet notifications

The trajectory of Amartya Sen

When Nobel laureate Amartya Sen speaks, people listen. The wide arc of his journey until now and the curiosity that drives him was on full display in a conversation with The Harvard Gazette. His passion for bicycling sat well with his other passion to engage with people and their circumstances, for instance.

“When the Nobel committee after you get your prize asks you to give two mementos or two objects connected with your work, I chose two. One was a bicycle, which was an obvious choice.”

“I went everywhere on bicycles. Quite a lot of the research I did required me to take long bicycle trips. One of the research trips I did in 1970 was about the development of famines in India. I studied the Bengal famine of 1943, in which about 3 million people died. It was clear to me it wasn’t caused by the food supply having fallen compared with earlier. It hadn’t. What we had was [a] war-related economic boom that increased the wages of some people, but not others. And those who did not have higher wages still had to face the higher price of food—in particular, rice, which is the staple food in the region. That’s how the starvation occurred. In order to do this research, I had to see what wages people were being paid for various rural economic activities. I also had to find out what the prices were of basic food in the main markets. All this required me to go to many different places and look at their records so I went all these distances on my bike.

“And when I got interested in gender inequality, I studied the weights of boys and girls over their childhood. Very often, it would happen that the girls and boys were born the same weight, but by the time they were five, the boys had—in weight for age—overtaken the girls. It’s not so much that the girls were not fed well—there might have been some of that. But mainly, the hospital care and medical treatment available were rather less for girls than for boys. In order to find this out, I had to look at each family and also weigh the children to see how they were doing in terms of weight for age. These were in villages, which were often not near my town; I had to bicycle there.”

Dig deeper

- I’ve never done work that I was not interested in (Amartya Sen)

The anatomy of social media

That social media has an underbelly has been well documented by many researchers. But when scientists invested in biology placed evidence that suggests the downsides of social media are significant, we sat up.

The lead author of the paper, Carl Bregstrom, spoke to Vox and we read all of what he had to say.

“My sense is that social media in particular—as well as a broader range of internet technologies, including algorithmically driven search and click-based advertising—have changed the way that people get information and form opinions about the world.

“And they seem to have done so in a manner that makes people particularly vulnerable to the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

“Just as one example: A paper—a poorly done research paper—can come out suggesting that hydroxychloroquine might be a treatment for Covid. And in a matter of days, you have world leaders promoting it, and people struggling to get [this medicine], and it being no longer available to people who need it for treatment of other conditions. Which is actually a serious health problem.

“So you can have these bits of misinformation that explode at unprecedented velocity in ways that they wouldn’t have prior to this information ecosystem.

“[Now], you can create large communities of people that hold constellations of beliefs that are not grounded in reality, such as [the conspiracy theory] QAnon. You can have ideas like anti-vaccination ideas spread in new ways. You can create polarization in new ways.

“And [you can] create an information environment where misinformation seems to spread organically. And also [these communities can] be extremely vulnerable to targeted disinformation. We don’t even know the scope of that yet.”

Dig deeper

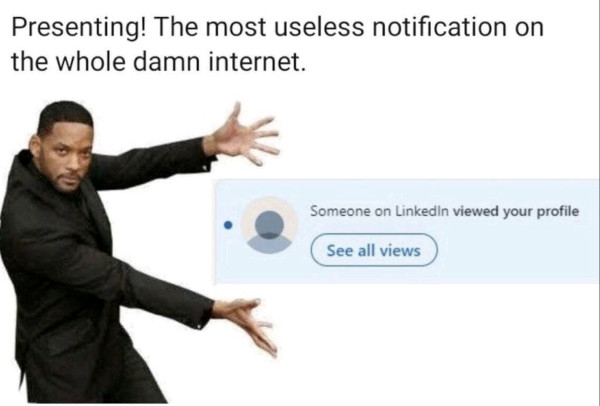

Internet notifications

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)