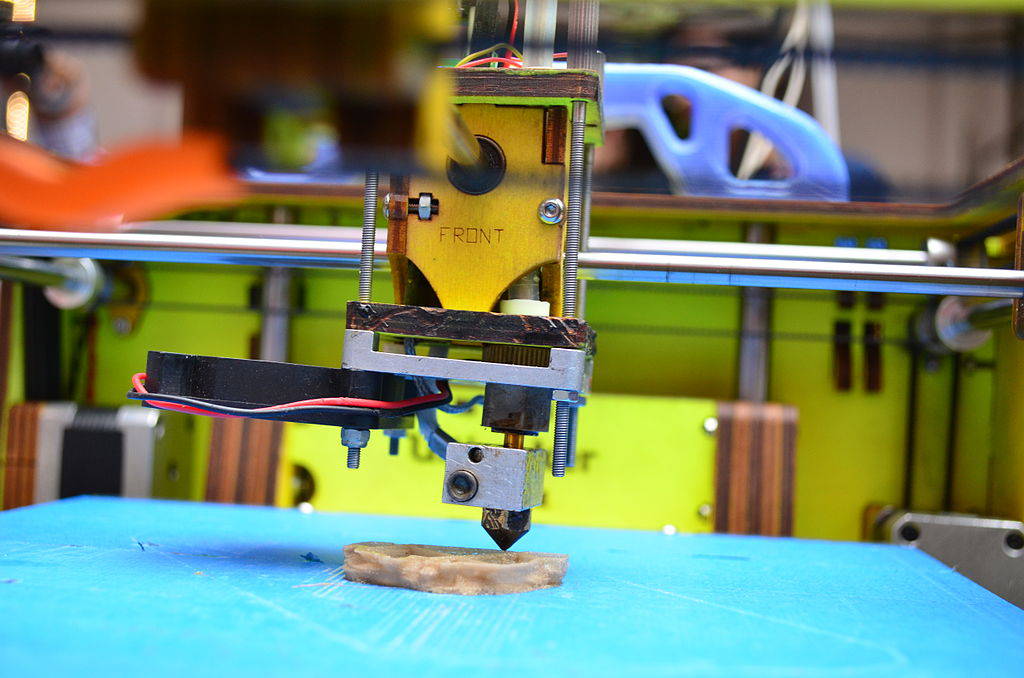

[Photograph by Subhashish Panigrahi under Creative Commons]

A few months ago, an Indian industrialist, from a family of Indian industrialists with a proud tradition of creating industrial enterprises, and jobs and development in rural India, put his concern to me. His factory produced turbines and pumps in a formerly rural location that were being exported around the world. He had recently installed a 3D printing machine to produce complex turbine blades. The machine, entirely automated, would do what dozens of skilled workmen were doing before. He had to use the technology for his factory to remain globally competitive. His concern was with the jobs that would be lost. And with the impact of his decision on his family’s mission to uplift the economy and living standards of the people in the region to which his family belonged.

Around that time, I was invited to participate in a discussion at the World Bank in Washington about the effect of technology on jobs. The principal participants were economists and policy makers from the USA and Europe. They were concerned about the creation of jobs in their countries for young people, most of whom were well educated, and even professionally qualified. Their countries’ economies were not creating enough jobs for young people, and they were concerned about the social and political implications of their high levels of unemployment.

Policy makers and socially responsible industrialists in developed as well as developing countries, who want to create jobs for young people, are concerned that automation and robotics in manufacturing (as well as services) will reduce the number of jobs. The fears have intensified with the advent of 3D printing technology, which enables complete products to be produced by a single, automated machine. A 3D printer can make almost anything, it seems—a complete garment from raw material, or a complex turbine blade, or even a pistol that can fire bullets. No doubt 3D printing will change the shape of manufacturing processes and factories.

The fear is that the role of human beings, and the number of jobs, in manufacturing will be further reduced with 3D printing technology. A completely robotized world, in which machines will make machines too, will require very few people. Perhaps the only people with incomes will be the capitalists who own the machines, their financial managers, and their lawyers to sort out property disputes among them! In this world power will be entirely with owners of capital and machines and it is feared they will keep using their power to throw human beings (who can be troublesome) out of the production system, replacing them with more obedient machines.

This scenario must be of great concern to India’s policy makers who fear that there can be socio-political turmoil if there are not enough jobs for India’s burgeoning youthful population, and who are expecting that a thrust for manufacturing, with Make in India, will create these jobs.

A doomsday projection of a world in which everything is done by machines and computers is unrealistic. Because, to complete the picture, one must also imagine what human beings will be doing in such a world. Consider how they will earn to pay for all the products and services produced for them by machines.

A doomsday projection of a world in which everything is done by machines and computers is unrealistic

Technology is only one force shaping the world. Human aspirations and, propelled by human aspirations, social and political forces shape the world too. These forces will create institutions and arrangements to protect human interests, including opportunities for work and sources of income for people, long before machines (and their owners) can eliminate them. No doubt the shape of production systems will change with technology. But people will not be eliminated. They will perform new tasks in enterprises which will take new forms. Technology will be used to shape these new enterprises.

No doubt the shape of production systems will change with technology. But people will not be eliminated

New models of enterprises will be founded on new concepts of production and management. Though old concepts, difficult to challenge because they have been successful so far, will try to prevent the new models from emerging.

An account of Mahatma Gandhi’s visit to the mills of Manchester helps to explain the power of embedded concepts. Gandhi wanted to study India’s competition—the factories with spinning machines—that were making his model of the hand-driven charkha in every household obsolete. He was impressed with the productivity of the machines he saw. However, he was put off by the noisy, humid, factory environment with lines of machines and workers crammed together in one building. He asked the manager why all the machines and workers had to be put into one building? Why could they not be dispersed around in villages, he asked? The manager pondered and replied that such machines were originally powered by steam which cannot be carried over long distances, so all the machines had to be crowded near the boiler. “But now they are being run with electricity which can be transferred long distances, so why are they still crammed in a factory?” Gandhi inquired. The design of the factory had persisted even though technology had changed.

The manager could have added, if he had thought about it, that another purpose for co-locating many operations and many people within a small space is the need for coordination of many operations and the need to control the people performing them. However, new technologies for computation and communications, which had not been developed when Gandhi inspected England’s textile mills, can now enable coordination and control of widely dispersed operations. Though technologies are now available for this, mindsets of management have not evolved in line with them. Vertical hierarchies for control, rather than systems for collaborative coordination, continue to dominate decision making structures.

Consolidation through ownership can make top down coordination easier no doubt. Because it is clear who the boss is. It is also easier for some to capture more financial value if they own all the parts. These are the logics for large, capitalist enterprises. But such monolithic enterprises have undesirable side effects too. The inertia that comes with their size makes them difficult to turn when the environment changes with new technologies, new customer requirements, and new competition. Innovation within them and entrepreneurship is dampened when the internal producers of value become employees of the monolith rather than owners of their parts of a large enterprise.

Re-orienting government policies

New technologies are disrupting old concepts of manufacturing and old models of enterprises. They can enable new forms of manufacturing enterprises whose scale can be increased by the aggregation of many dispersed activities rather than the sizes of their factories. Meanwhile the ‘theory-in-use’ that competitiveness requires large ‘scale’ production units continues among corporate managers and policy makers. In this view, the size of these factories drives down their costs, improves their competitiveness, and enables employment of thousands of persons. Large factories like Foxconn’s in China, which employ hundreds of thousands of workers on one site, are icons in this world-view.

India’s policy makers are trying to change land-use and labour laws in the country to enable the formation of such large factories. Their efforts are going against the socio-political tide of India. For their strategy to succeed, they have to take away rights to protection that owners of land and labour have been provided in democratic India. Whereas in China, labour and land rights were consolidated with the state (and the Communist party), making it easier to create such large factories and industrial clusters. It is worth noting that the Communist party is now giving labour some rights to organize, and is also becoming more careful to avoid confrontations on land issues. Indian policy makers are realizing perhaps that it is easier to give people what they do not yet have (the China situation) than to take away what they have (the India situation).

However, India’s policy makers should not lose heart in their battle to expand manufacturing and create jobs. They would do well to stimulate the growth of tomorrow’s networked enterprises which will come about with unstoppable changes in technologies, and not pursue yesterday’s paradigm of large, monolithic factories.

Two forms of technologies are combining to disrupt old-style manufacturing monoliths. One is digital technologies that enable multiple operations to be done on one machine on a small scale, such as desktop publishing and 3D printing of material objects. These technologies are enabling manufacturing enterprises to be viable on very small scales. For example, even small and medium enterprises (SMEs) can use 3D printers that cost less than $1,000.

The other set of technologies that are changing the shapes of enterprises enable efficient connection of widely dispersed suppliers and customers. These are creating new disruptive business models, such as Amazon, eBay and Uber. In India, such technologies are changing the shape of retailing industry models. ‘Big box’ retailing models are being deconstructed with online ordering and delivery in small lots to customers, rather than customers coming to large retail stores to buy large quantities at low cost. In India’s case, these emerging models take advantage of the proliferation of smartphones in India, and they circumvent the problem of acquiring large plots of expensive land for the big-box stores.

The combination of these two sets of technologies is enabling formation of large networks of many small enterprises in manufacturing and in services. Such models of enterprises will cause less political strain, in India at least, than the promotion of large monolithic enterprises. Moreover, such networks of many small enterprises will generate more opportunities for growth of small enterprises and employment.

Networks of many small enterprises will generate more opportunities for growth of small enterprises and employment

On August 15, 2014, in his first speech on India’s Independence Day, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Make in India campaign. His government’s efforts to change land and labour laws have been stalled by expected social and political resistance. On August 15, 2015, he seemed to change tack and announced a new idea—Start Up India—and said that India needs many small enterprises employing as few as two or three persons. Such small enterprises do not need much land to operate: they only want some legitimate space. Nor would they be concerned whether laws limiting their powers to hire and fire workers apply when they have 100 workers or 300. They want to be saved harassment by officialdom, and they want easy access to finance. Fortunately the government’s efforts to ease doing business, and to make institutional arrangements to enable SMEs to get finance are progressing.

Such small enterprises do not need much land to operate: they only want some legitimate space.

The country needs a new vision of manufacturing enterprises: not massive factories, but large networks of nimble, smaller enterprises. Technology developments as well as India’s own socio-political reality drives to this vision. This vision should drive policies. Political capital should be invested in this vision.

A vision of the impact of policies on the lives of human beings must drive the vision of policy makers

A final point. A vision of the impact of policies on the lives of human beings must drive the vision of policy makers. Leaders of manufacturing enterprises too must realise that the only sustainable source of competitiveness of their enterprises are the people in them. Human beings are the only “appreciating assets” of an enterprise, because they can improve their own abilities if they are motivated to. The value of all other assets—including machines and robots—will depreciate with time. It is only people, and not the machines, buildings and materials, that have the ability to learn and improve their own capabilities, and human beings can improve the capabilities of manufacturing processes and machines also.

Human beings are the only “appreciating assets” of an enterprise, because they can improve their own abilities

The resource that India has in greater abundance than any other country today is young people who need to be gainfully engaged in productive enterprises. Entrepreneurs wanting to make in India must consider this resource as their asset, and a principal source for their global competitive advantage, and not as a headache to be avoided.