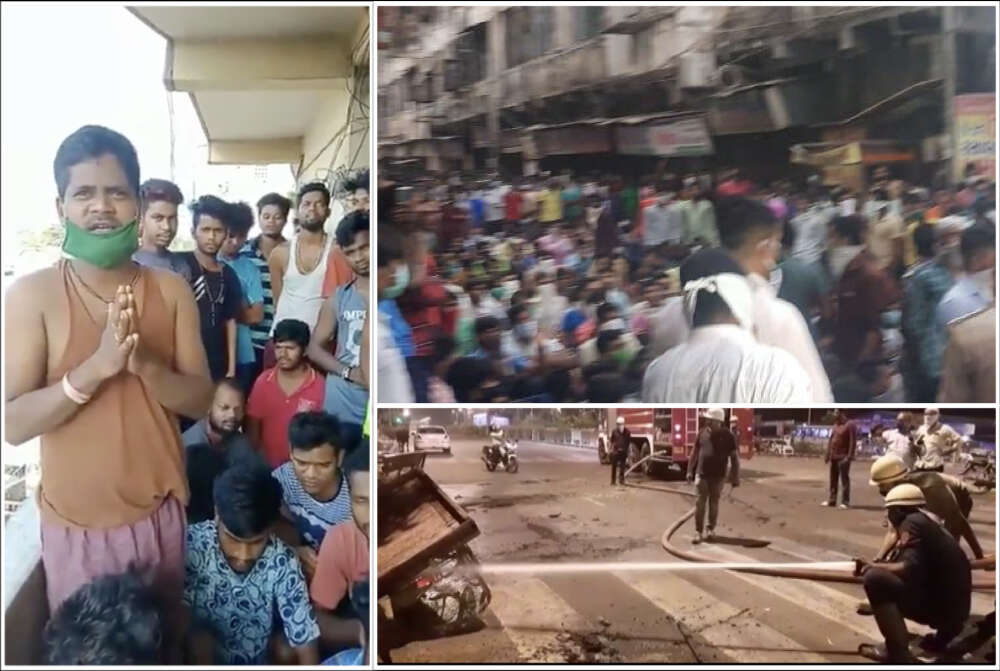

[Clockwise from top: Migrants from Jharkhand stuck in Surat pleading for help on April 09; Migrants take to the street in Surat amidst lockdown on April 15; Firebrigade tending to the blaze post the street violence by migrant workers on April 11. Photo credit (clockwise): Migrants pleading for help- screenshot from video tweeted by @JharkhandJanad1; Migrants on Streets (cropped) - tweeted by @nistula; Firebrigade tending to blaze (cropped) - tweeted by @ANI]

Passions have been boiling over at Surat, the busy textile hub. At least twice over the last few days, disturbing videos have surfaced on social media of more than a thousand angry migrant workers protesting on the streets.

Workers demanded their salaries be paid. With the prospect of any gainful work receding, they simply wanted to go home. Now, with the national lockdown extended till May 3, palpable signs of social unrest are coming to the fore. It is still unclear when the factories where they worked will have enough orders for the owners to resume operations.

Last year, the Quipper Research team, led by co-founder and CEO Piyul Mukherjee, started an on-going blog called Ground Realities to study the impact of the Great Indian Slowdown on families. It was an attempt to understand what is happening inside people’s homes and in their lives. The ups and downs, as reflected in their social and economic worlds. The all-women team at Quipper stepped out to meet common people across various towns. And asked: Is your life much better now than it was five years ago?

The first pit stop was Surat. You can read the first despatch here.

Since then, the pandemic and lockdown has thrown the economic and social situation across the country off kilter. Surat included. The specter of reverse migration, the first signs of which were evident last year is now a full-blown crisis. With no buses and trains plying, thousands of workers are trapped, without work and in some cases, without food—and almost always, no income.

The ground beneath their feet had completely shifted. And so, starting early April, the Quipper team once again picked up the threads of their conversations in Surat.

These are the most recent despatches based on conversations with the owners of two micro businesses in Surat’s large textile hub. It provides a poignant first-hand account of how the lockdown has affected not only their lives, but that of workers dependent on them for survival.

How Ashish turned from entrepreneur to caregiver during the lockdown

By Ipsita Bandyopadhyay, Nishita Thaker and Piyul Mukherjee

“But where will they go? If I do not give them food, how will they survive?”

[Ashish Raut with his wife and two-year-old daughter. Photo credits: Quipper Research]

Ashish Raut

Occupation: Owns an embroidery unit in Surat, with 12 ‘karigars’ working for him, on daily wages

Residence: Rented ‘rooms’ in the first floor of an established chawl in Varachha, Surat, otherwise he is originally from Odisha

Family: Wife and two-year-old child

Ashish Raut has lived in Surat, the commercial textile capital of India, for more years than he can count on his fingers. He apprenticed with his mama (maternal uncle), who owned a few embroidery machines, and later branched off on his own.

When the going is good, he employs about twenty artisans, most of whom are migrants from states such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Odisha. Raut owns two embroidery machines on which he is still repaying the loans off in EMIs. Each machine can seat ten people working on a separate item of clothing at a time.

When the 21-day nationwide lockdown in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak was announced, Ashish was at his ‘karkhana’, his factory, instructing his workers about an urgent delivery that was due the next day. The previous Sunday’s janata-curfew had delayed completion, and his karigars were working overtime.

Engrossed with fulfilling commitments to the cloth stores within the textile markets of Surat, he only learnt about the lockdown on his way back home, late at night.

A sense of panic was surging in the neighborhood. Shops were shutting down, public transport was suspended, and rules on the ground were hazy. Anxious residents were queuing up at the local grocery or medical stores to stock up.

Ashish’s first reaction was of relief. His young family had gone back to their village in Odisha for a function and would be with family members in the village through the closure.

He immediately turned his scooter around and rushed back to the karkhana. Normally the karigars would be paid for the consignment they were working on, once monies were received from his clients. This can take as much as three months because rolling credit is common across the city.

Ashish brought forward the dues to each karigar, and paid them with cash that he managed to withdraw from the ATM. Before it ran out of money.

The karigars were mystified. And bewildered.

“If I did not pay them, how would they survive?” he reasons.

Despite the goodwill shown by their employer, other unforeseen challenges awaited the men at the factory. Six of Ashish’s artisans realised that they could not continue paying the rent through the lockdown and decided to vacate their shared rooms immediately. These were ‘single’ men, whose families lived back in the village.

With no shelter and no transportation available to go back to their hometowns, it was a question of basic survival. Of figuring out how to get roti, kapda aur makaan. In solidarity with their plight, Ashish asked the karigars to move into his karkhana premises.

On his scooter, he could rush around to pick basic food supplies and organise cooking gas.

Ashish makes a twenty-minute sortie each day, to and from the karkhana. When the traffic policemen stop him, he explains the fate of his hapless karigars. Fortunately, it fits into the definition of an ‘emergency’ and he is allowed to move around.

[Samples of Ashish’s embroidery work by his team of karigars. He buys the thread required for the work. When done, each of the items fetch about Rs 90 from the textile shop owners. Photo Credits: Quipper Research]

The boys are petrified of moving out of the karkhana during the lockdown. They came across a video of the Uttar Pradesh Police unleashing a reign of terror on returning migrants and are afraid that this could be their fate. When he witnesses the plight of his workers, he feels he is better off. And when he visits the karkhana, he also eats with them.

“I never learnt how to cook”, he says sheepishly. “With my wife away, this works well for me”, referring to the roti and sabzi made by the workers.

Hardship has moulded the disparate men into a close-knit unit.

“I have a decent place to sleep, I have food, I will be okay. It is so difficult for my karigars, they are sleeping under the machines. I don’t have any right to complain.”

He goes on to say, “When I hear about the coronavirus, I am grateful to be alive and that I can contribute in keeping these people alive. That is most important.” At this moment, basic survival and the sense of being responsible for the lives of a few young men, has taken precedence over fears and anxieties regarding loss of investment and business.

Alleviating the situation, the building secretary of the chawl Ashish lives in, has just informed the immediate neighborhood about food supplies being provided by the administration.

Ration card holders would be eligible to receive supplies of essential food items from the beginning of April. Brought to their homes. He has been informed that non-holders of ration cards, such as him, would also get food grains after a few days.

And once he receives his supplies, he plans to carry the items to his factory.

As Ashish awaits for normalcy to return, he believes that the government is doing its job well and the welfare schemes they are rolling out will eventually benefit him in some way as well.

How Harekrishna is feeding his new extended family of 22 members

“Kya maange sarkar sey, bas chahte hain ki hamare purane din wapas aa jaye [What can I ask from the government, I just want our old days back]

[Harekrishna Kushwaha (left) at his tea stall ‘Maurya Sweets’ in Umarwada, opposite New Bombay Textile Market, Surat. Photo credits: Quipper Research]

Harekrishna Kushwaha

Occupation: Owns Maurya Sweets, a tea and snacks stall in Umarwada, opposite New Bombay Textile Market, Surat

Residence: Bardoli, Surat. He lives here with two brothers in a two-bedroom ground floor house. All three families, including the wives and children, stay together

Maurya Sweets is a typical Indian tea and snacks shop on a busy street in Surat. Apart from tea (at Rs. 10) and coffee (at Rs. 14), it sells samosas and jalebis. With the economic downturn, Harekrishna Kushwaha had pared down his staff to four from eight, in 2019.

Back then, just a few months earlier, Kushwaha was exasperated at his inability to get a Mudra Loan, to expand his business. His CIBIL score fell short of 700 by ten points, and his loan request was rejected by the bank.

Taking a loan from the ‘entrywala’—as the informal loan sharks are called—was the only option left, where interests were as high 5% per month.

He expressed his frustration with the system that he believed to be pro-rich and anti-poor. And had felt let down by the government. “I don’t even know where to complain,” he had said. “I want to grow my dhandha (business), but there is no support from the establishment”.

“Even if the government introduces a new scheme for loans to small businesses like me, banks don’t give it to us. They either evade customers like us or make up some excuses saying either that the scheme isn’t available right now or cite some discrepancies that pertain to eligibility criteria. They show us the door each time we seek answers.” But that was back in a different era.

With the Covid-19 pandemic and shutdown, there is a new universe to be inhabited. Kushwaha had no alternative, he says, and has brought home his staff of four men who used to stay inside the shop at night. The police don’t allow it now during the lockdown.

His already limping business is now at a standstill. “Since the last two months, I have no money to pay my employees,” he says. The least Harekrishna felt he could do, was ensure the working men are regularly fed and taken care off. That is why as a result, there are 22 people living in his house right now.

“They are not from here. Where will they go at a time like this? What can I do even though I’m struggling with money? They are in a condition that is far worse than mine,” he says.

But he is hopeful. By early April, the municipal authorities had reached out to every resident in Surat. “We haven’t got anything or heard of anything from the government until now. But just today, someone from the authorities came to our house and took down our names, enquired about how many are living here. Let’s see what happens.”

So far, people in the community have been helping the helpless survive. The virus has spurred acts of kindness even as those slightly better off, support others to get through these difficult times.

Harekrishna shares the story of his Kucchi neighbours. Those who were struggling with buying the daily food essentials, were helped by other families living in the society, pitching in and sharing their meagre staples.

“Twenty families usually stay in our building. But we are currently sheltering a little over a 100 people.”

Social distancing is not a privilege of the poor.

“At this time, there is nothing we can do about the situation. There is huge uncertainty. We are living in a state of constant fear,” he added.

Harekrishna and his family have stocked up rice and pulses that he believes will feed all 22 of them until the lockdown ends. “We all eat the same thing, our family and my co-workers,” he says.

But, as the uncertainty of the lockdown period looms, the family has started making small compromises by cooking a single dish for each of the 3 meals to ensure that the stock outlasts the lockdown.

Now that the lockdown has extended beyond the 15th of April, he says that the family can survive for another month but beyond that would be unimaginable. Any news pertaining to the handling of the virus is a nightmare. Even when it is a distant ‘mahamari’.

When asked about how he is dealing with the growing unrest, he says, ‘I am just grateful that we have life. I am alive and have kept these people alive. The government is doing what it needed to do.’