[Photo by Pedro Santos on Unsplash]

Dear Nayantara and Anugraha,

I can hear the both of you giggling in the other room as you stream a movie on Netflix and tell mama how sorry you feel for me because you think I’m at work.

Actually, I’m not at work.

In fact, I’m writing a story—for the both of you—about how things got to this point where the both of you can now lounge there on the living room, even as you chat with your friends and tell them how grumpy I appear to you now, and tell them how awesome the movie you’re watching on Netflix is.

So, this story is about all of what has happened over the past 25 years. A journey that started on August 15, 1995 actually. There are so many stories to tell. Makes me smile when I think about it. You’ve heard of Yahoo, right? Once upon a time, Yahoo was the biggest thing on the internet.

And back in 2000, the company’s co-founder Jerry Yang was in India for a big bang India launch. After the press conference was done with, there was this after-party. There was this big crowd and I was standing by the bar when he came along. His sister was there too and the three of us got chatting. He was a billionaire at 31 and came across as a real nice guy. His sister looked real pretty as well. The three of us hit it off. I don’t know what I was thinking, but just like that, I asked him, what does it feel like to be a billionaire and have women swooning over you?

And Jerry laughs, puts his arm on my shoulder, and tells me in a whisper, “Can you introduce me to a nice woman here you think I may like?”

The three of us laughed, had a drink, shared some jokes, spent some time talking about the future of the internet. I thought that was it. Some random conversation. I was young and tipsy. Over and out.

Then in 2008, I met Jerry again. Much water had passed under the bridge. Yahoo was being acquired by Microsoft. He had gotten married. His sister wasn’t there. He looked older. I’d grown a bit wiser as well, I think.

I don’t think he remembered our earlier encounter. But this was at the same hotel. And I go, “Hey Jerry! What’s with you and Microsoft?”

And he smiles and says, “There’s a joke inside Yahoo that Jerry is wrong most of the time. I underestimated the number of users, I underestimated the speed at which connectivity has increased around the world… and so I stop trying to be predictive… Everything on the internet has surprised me.”

The both of us smiled. I knew what he was saying. And he knew I got what he meant. Every tech journalist worth their salt knows they never get it right. They can only speculate. That’s what makes the story of the internet such an amazing one.

Now that I look back, this day, that year, I was just out of college and a rookie reporter at Financial Express assigned to cover technology. Us technology journalists were a small breed and were among the few who got what the internet meant.

No girls, the internet isn’t Google. That’s a search engine.

If I could explain it in a single line, if we connect all of the world’s computer’s together, we now get a huge network of computers. Because when networked, everything that resides on it is available to all those who are on the network. That’s the internet for you. And how do you look it up? You use a search engine. Get the difference? Okay, let’s move on.

Academics across the world had figured ways to create a network. Those in India had created ERNET, an acronym for Education and Research Network. I had only heard of it. Only those at premier engineering colleges and academics had access to it.

Then 25 years ago, a company called VSNL announced it will make the internet available to people like me. I can’t tell you how excited I was. This had the potential to change how I used my computer.

Like N Dayasindhu told NS Ramnath and me yesterday, until the internet happened, the computer was just a fancy typewriter. He was right. There was nothing the computer could do for me that a typewriter couldn’t. Unlike him. He passed out of IIT and could think up ingenious things such as code. I was a writer.

My day job meant going out to report from the field and then writing about what I saw. I could do that on a typewriter as well. I didn’t need a computer. It added no real value to my job. It was just an impressive gadget.

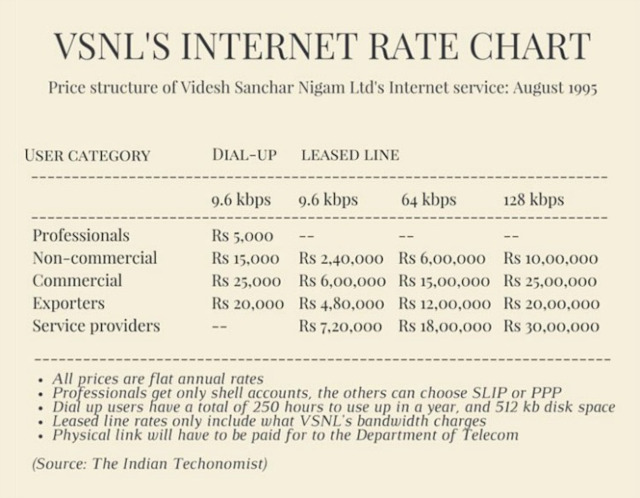

But if a computer could hook up to the internet, in theory, the world’s knowledge would be at my fingertips. As things would have it, one look at the prices VSNL had in mind, and my heart sank.

You see that table there? I don’t know if you can even wrap your head around what that means. How do I even begin to explain this to you?

Let me do a dummies version for you because I don’t think you’ll get this otherwise.

- Access to a “text-only” version of the internet (or a shell account as it was called) would cost Rs 5,000 per annum. Now, who wants that?

- If I wanted to access images, it would cost Rs 15,000 per annum. But that’s where the catch was as well. The download speed was 9.6 kbps. With that kind of speed, you wouldn’t be able to send an animated smiley on SnapChat.

- So, the next option looked like going for a leased line of 64 kbps. You do the math on that to figure the speed. On a pay cheque of under 10k a month, there was no way in hell I could afford Rs 6 lakh each year.

Even if I could afford it, getting any internet connection at home wouldn’t be easy. We’d have to apply for it and there was a waiting list. Those were the days when even a landline at home was a luxury. We had gotten one after waiting for over a decade.

So, I had to keep my fingers crossed and was hoping the bosses in office would get an internet connection. It happened. And very soon, one corner of our office had a computer with a dedicated leased line.

Our boss, RN Bhaskar, was a kind-hearted soul who wanted all of us kids to get familiar with technology. But you know what? And I kid you not on this. The moment he stepped out of sight, we’d get into fist fights over who gets to use the machine first. It was another matter altogether that we didn’t know how to access the internet. He mentioned something about launching a browser and typing the name of the website into it.

But what was a “browser” supposed to mean?

A crash-course by him later, we figured a browser is a piece of software that must be launched to “surf” the internet. This sounded so cool. He suggested Netscape is cool and that’s what we latched on to. It was a matter of time before the internet exploded and content of all kinds started to sprout.

To create it, new entities were coming up and I was in awe of entities such as Lycos and Altavista. These were search engines that pre-date Google.

We had only heard of email. The ones on offer were clunky and we’d change it each time a new service appeared. Until the slick Hotmail emerged out of Silicon Valley in 1996. It was co-founded by Sabeer Bhatia, an Indo-American engineer. I was one of the first people to latch on to it and got an email address of my choice. Having a Hotmail email address was thought of as very prestigious. Microsoft eventually acquired the company for $400 million and Bhatia got to be a very rich man.

Stories such as these were making its way to India and it seemed like this awe-inspiring mysterious thing piece of infrastructure that few people knew about. I happened to be among the privileged ones who had access to people at work who were shaping the India story.

Now that I look back, from the perspective of a news hound, there were the soft-spoken ones such as Rajesh Jain, a hard-core technologist who was at work on a web portal called indiaworld.com; then there was the flamboyant Ajit Balakrishnan who created rediff.com; and assorted people who claimed to have created Silicon Valley. Us desi journalists were impressed initially.

As for Jain and Balakrishnan, I spent time listening to both their narratives and how they imagined the India story will shape up. They couldn’t be more different from each other.

While Jain worked out of a cramped office and ran a lean ship at Nariman Point in Mumbai, Balakrishnan had a spacious office and an eclectic bunch of people—many of whom continue to be friends—inhabited the place.

Traditional media companies looked on enviously as Rediff.com started gaining traction and eyeballs. It went on to acquire a newspaper in the US called India Abroad News Service. Balakrishnan had other plans as well. This included a range of offerings along the lines of an email service and a shopping portal. It was Amazon plus Gmail for Indians.

But what most people didn’t know then was that the Indian Express group was seeking his advice to build out a digital arm called The Indian Express Online Media Ltd (TIEOML). The group was the first off the block in the mainstream media to launch an online edition of the newspaper.

Balakrishnan, however, was thinking bigger and went on to list Rediff on the NASDAQ sometime in 2000. This was the first for any e-commerce company in India. He was in the headlines every day.

Meanwhile, Jain moved on and TIEOML started thinking up ways to catch up with Rediff. Because email hadn’t gained traction then, this arm of the company used to facsimile (fax) an abbreviated version of all major business and political news—from Indian Express and elsewhere. This contained summaries of articles with a code attached to it. If a subscriber wanted to read more, they’d have to punch the code into their fax machine. A full version of the article would be pulled out of a database powered by software called FoxPro and would be delivered to the subscriber by fax again. It was the offline version of ‘click on a link’. In theory, a great idea.

But when email went mainstream, fax machines became redundant, delivering newsletters became easy, and clicking on links easier still. The business suddenly looked like a horribly expensive proposition and it had to be disbanded.

Incidentally, that was also the time I recall getting a call from a public relations firm. They insisted I go in for a press conference at short notice because “it is a big deal”. When I walked into the hotel, B Ramalinga Raju, the founder of Satyam Technologies, was beaming. Jain was on stage as well, along with some of the more prominent merchant bankers then. His expression, as always, was stoic.

Raju went on to announce Satyam had acquired IndiaWorld.com for $117 million. Our jaws dropped. We didn’t know what hit us. It was the largest such deal for any company in India. He had other plans as well. Sify.com, as the new entity was called, would be setting up internet cafes across the country—places where people like me could walk in and browse the internet on a computer for a small fee. It sounded like such a lovely idea! It’s another matter altogether that I went back to file a story that said Satyam had overpaid for IndiaWorld. No one seemed to mind me saying that. It was an opinion.

As for Raju, he promised to deliver cheaper access to the internet to users at home. VSNL too had dropped prices significantly and more Indians were getting online.

Between Balakrishnan’s ascent to Nasdaq, Jain’s exit from IndiaWorld and Raju’s promise to drive down price of access to the internet, and assorted stories from Silicon Valley making it to the front pages every day, it was inevitable “The India Story” would start doing the rounds.

I was young. I was impressionable. I was naïve. I bought into all of it—for a while. Raju was eventually convicted for fraud and went to prison. The dotcom bubble burst. Life started getting back to doing routine things. Such as saving money.

More people like me saved enough money over time to acquire a machine. I recall getting a Compaq, no less! With a Pentium chip in it. I don’t know if you’ll ever know what that means. Because until then, the only machines I had ever used had been built over time. Piecemeal.

Between us friends, we’d scour the markets of Lamington Road in South Mumbai for parts—like hard disk drives, memory, keyboards, monitor—and when all had been acquired, we’d assemble our own machine. If it slowed down, we knew how to get more juice out of it. Or uninstall some software. Better still, kick the machine to run faster. Boy, that was some life!

But the thing about logging on to the internet from home then was that we needed a modem. In turn, this had to be connected through the same port that routed calls to the landline. This was a time when we thought speeds between 128 and 256 kbps were high-speed internet. While there was no way you could stream anything of consequence, we had cottoned on to chat, and attempting to download music and movies.

So, here’s what we’d do. Late in the night, after everyone had gone off to sleep, we’d schedule downloads. And hope no one would call. Because if anyone called while a download was on, the connection would drop and our download would go kaput. How large would these downloads be? Well, to download an album of songs using a piece of software called Napster could take overnight. I hate to admit this, girls. That’s why a lot of kids from our generation used to watch pirated movies with low resolution. They were easier to download.

To be fair to the ecosystem around us, there were people pushing the system.

In popular imagination, Shammi Kapoor is remembered as an actor. But after he stopped acting, he was almost activist like in his zeal to amplify in the public domain what the internet can do for the masses.

And then like my friend Venky Hariharan reminded me a little while ago, very little is spoken in the public domain about technology evangelists such as K Pandyan and Atul Chitnis who argued for the cause from all forums that matter; or the role that the then chairman of VSNL BK Syngal and technology director Amitabh Kumar played to implement the internet in India.

In fact, did you know that when VSNL launched the internet in India, China still had to get its act together?

Even as I write this, I can’t get around that it seems like just yesterday when we were ahead of China. And now we talk about China as if it’s some kind of a tech super-power. Did things deteriorate? Did it stagnate?

Let me put it this way. It didn’t deteriorate. If it had, you girls wouldn’t be at home streaming that movie on Netflix. I wouldn’t be able to work out of home like so many people are now even as a pandemic plays itself out. We’d be worse off. But we lost the plot somewhere.

By way of example, there’s this project called BharatNet. It was thought up in 2011. The intent was to connect all of India’s 625,000 villages with a minimum broadband speed of 100 mbps. Phase I of the project didn’t take off as planned. If I have it right, Phase II of the project ought to have been done by December 2019. I don’t know where things stand. Like Dayasindhu told me earlier, we don’t know if 100 mbps is good enough now. Incidentally, what you have access to at home now is 250 mbps.

I know I’m getting a bit sentimental out here. But this Simon & Garfunkel song comes to mind,

Time it was, and what a time it was, it was

A time of innocence, A time of confidences

Long ago, it must be, I have a photograph

Preserve your memory; They’re all that’s left you

Reason it comes to mind is because as a tech junkie, I know there are a bunch of us who have been very vocal about what India needs. On India’s Independence Day, and the 25th anniversary of the internet in India that makes it possible for you to experience it, I wish you’ll grow up to be vocal about what you want and fight for it. For yourself, and for all of us Indians.

Much love,

Dada