My family is quite insane. Somehow we have normalised the fact that visiting upwards of 100 pandals during Durga Puja in Kolkata is par for the course. Those who turn up and visit a mere ten, are doing themselves a disservice. This year our friendly and over-indulgent editors asked me to come up with one of those internet friendly articles using our annual nutso zealotry as the base of research. I began cataloguing my short-list, eliminating at first only those devoid of artistic note. The short list was 120 (all overwhelmingly available on this insta story if you’re interested). Thus began one of the hardest processes that my otherwise shrewdly discerning eye had to engage in.

But before that, a quick word of context. Covid-19 had previously strangled budgets and thus enhanced creativity. All the stops came out last year (which you can read about here), since in 2021, UNESCO decided to add Durga Puja to the Intangible Cultural Heritage List. On this recognition of the centuries of Durga Puja (recently I attended one which was 350 years old, which is older than the foundation of Kolkata) and the myriad of art on display, the British Council commissioned a report. This report spoke about many many good things, but also made recommendations on economy, cultural safeguarding, and strongest of all, environmental footprint. Bengalis being Bengalis pored over this report, and I’m glad to say embraced its recommendations.

Before I dive into rankings, I just want to address one more thing. Should you go? Depends on your enthusiasm. I’ve often compared it to the Rio Carnival, which is a mess and liable to upset your sleep cycles, but a beautiful and unforgettable experience. Sure, it’s not for everyone. But if you were interested you can now (a) purchase a priority pass that gives you an uncluttered entry to 24 pandals a few days before the festival starts and (b) there are toilets everywhere. I hope with that, you’re booking your flight tickets for next year. And now, on with the rankings.

Even before we started I ran into problems. What are the criteria? Beauty, message, quality, environment friendliness, uniqueness—all of these are factors. Some like Barisha Club had a strong anti war theme (with people trapped in concrete pillars toiling to break out), but had a lacklustre Pratima (idol). Others like Sitola Tala decided to grow real vegetables in vines around the pandal, timed to the actual puja days. But despite their strong commitment to the cause, they did not have a striking artistic sensibility. Therefore any criteria are simply factors and these factors must also have weights, and any weightage system can also be disagreed with.

Second, it is absolutely impossible to cover all of Kolkata’s 3,000-plus pandals, which grow more in artistry every year. Even until the last day, I received hot tips of unmissable pandals, and I know of at least two that I missed that might well have been contenders for the top 11. I also avoided some that quickly approached super-crush density and would not justify the returns to my time (eating up an hour or more), when they were unlikely to make the cut. Thus Deshopriyo Park and Sreebhumi were avoided, but I, and consequently you, did not need a Disney Park themed pandal, so that’s alright.

Third, in a mad dash to cover as many pandals as possible, it’s not possible to cover all of them at the best times, or best lights. Some delightful pandals could only be visited while I was sardined between sweaty Bengalis. The pandal’s carefully chosen soundtracks would be marred by police whistles urging us to keep moving. Others were visited during the day, with the majesty and beauty of the lighting lost on us.

And last, there is fatigue. The bulk of the pandals weave into one another, and only a few stand out in memory. Tiredness and mild irritation as a similarly desultory public decides to stand just at the opening bottleneck, to go through their 20 selfies to pick the best one, leads to a low-level exasperation that is probably not the best mood for evaluating the artistic.

And yet, I present to you my list. It comes with many biases. Knowledge of previous years means I cut down recycled themes. Some of the budgets are known to me, and therefore I’m amazed when a pandal makes Rs 15 lakh look like Rs 50 lakh, than when someone spends crores and makes it look like a Will E. Coyote drawing. I realise that unlike my Oscar predictions, where someone is unlikely to know me or take umbrage at my condescension towards their crafts, friends of family, or friends, or family may be involved in pujas, and have put in much more than their hearts and souls into the making of them, only to be dismissed by a critic, who was too sleepy to number his insta-stories correctly, and too bad at Bengali to get the majority of the spellings right.

11: Beliaghata 33 Pali

Eleventh from the top, despite much vying and pushing from other contenders, but after much confab, absolutely refusing to leave our list was Beliaghata 33 Pali. You may or may not be searching for it, but it absolutely arrests your attention with this gigantic figurine that appears to be hewn from earth.

The inside is a lot less commanding, with stalactites, and roots, with unchecked hillside construction as its theme, a video projecting a sky and a beautiful pastel Pratima against a blue backdrop. I thought the soundscape represented earthquakes, but it was the dynamite used to clear the way. The artists drew inspiration from a disaster in Sikkim. The Pratima, from its woeful London South-Bankesque lion to its delicately curled bull horns elevates the otherwise humble interior pandal artsmanship. But the giant earth Gollum outside, afflicted and wretched, in concept, is as striking as a Rodin or a Giambologna. Walk up close and you realise that he’s astonishingly crafted from either canvas or marking cloth, made solid by dried paint.

10: Tarun Dal

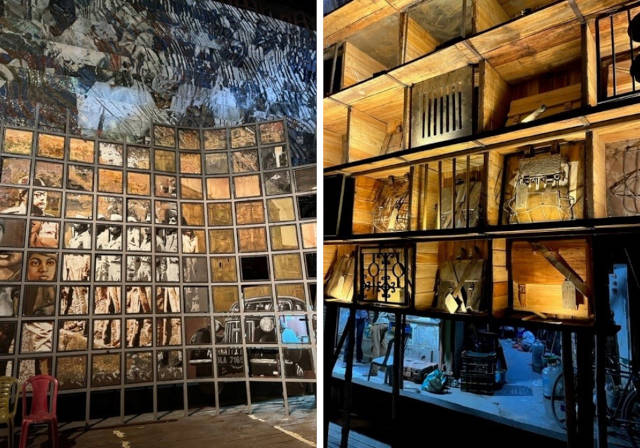

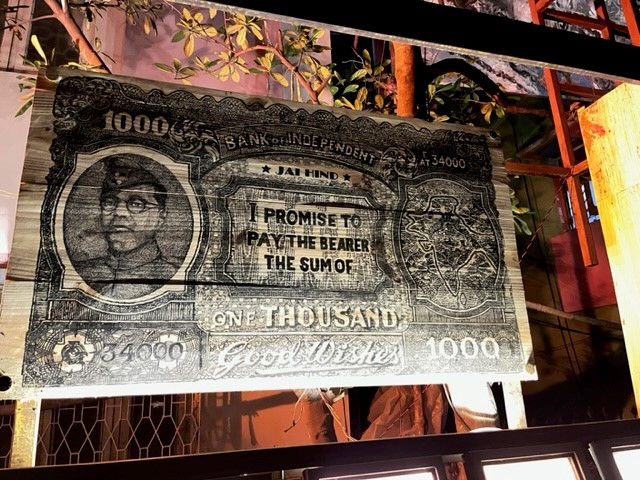

Tenth from the top is Tarun Dal, and it went up against some tough competition to make the cut. It features the lives of women in Subhash Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army (and also their part in local armed resistance).

The ones in the armed contingents such as “Jhansir Rani”, were mothers, wives and daughters that left their homelands to train on foreign soil. It makes the list mostly for its fastidious research. Any museum would be proud of the graphic design and the creative ways the limited information from the time is brought to life.

Artefacts, I believe, were recreated and aged, such as the deadly combs that these warring women used as weapons. Road-signs from across the subcontinent show the geographical spread of these warriors. And of course, the Pratima herself is a warring woman, her weapons raised, but her other arms outstretched as if to say “what is it that you think you can do to me?”

The reason that this pandal is lower than the top, and nearly dropped from the list was its choice of including a submarine as a centrepiece. The lighting was also incongruous with the rest of the pandal, and its inclusion was because Bose made an escape in a sub, which to my mind had nothing to do with the women they were celebrating in the rest of the pandal. I should note at this point that my views are my own, and these views remain happily ignorant of any political undertones that this or any other pandal may have (a fair few of them had Stars of David on them, though that may be inadvertent).

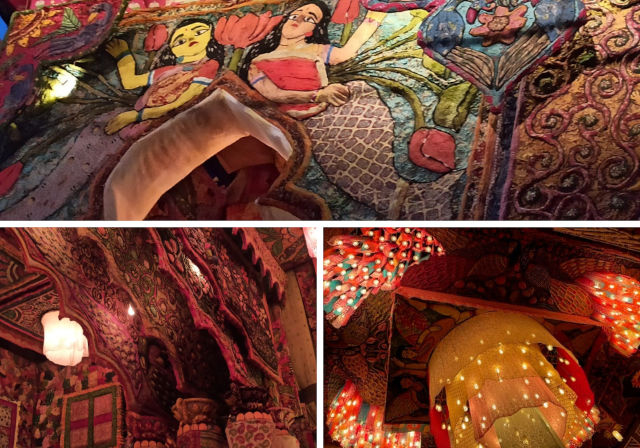

9. Mitali Kakurgachi

Ninth up comes the stunning Mitali Kakurgachi. Made entirely of recycled cloth, mostly old saris embroidered together (I would say it is kantha, but it wasn’t). Every inch of the pandal from inside to out was filled to the brim with detailing, story and style. But people have done mosaics before. There is an impressive skill that collage artisans have to have, that is able to look at the whole and the part of the whole together. Unfortunately the photos I have do not do it justice, but the ability to match textiles, which are not in the same colour grade, and not in the same texture, and yet make it seem coherent is quite a feat. More than that, the reason it doesn’t work in the photos is that it veers teetering close to sensory overload, but instead of putting you off, the maximalism pulls you in, to look more closely at the inserts.

My sister tells me that the type of saris used are the type that get handed down several times before they finally get exchanged by the kilo outside Girish Park for utensils. In a world where a British Council report has just told you to cut down on your use of Styrofoam (Kolkata’s usual go-to crafting material for Pujas), stitched together saris are the perfect substitute.

I personally didn’t like the Pratima, but choosing to have husband and wife stand like a family was oddly equalist, where usually it feels Shiv, when gaining that much space, steals too much of the spotlight. It’s helped by a cloth mural that enshrines them, which happens to be all the avatars of Durga. I’m also intrigued by the fairly neutral, borderline unhappy faces on most of the depictions on the walls. It makes me feel like they have a Kahloesque deep inner monologue. (That and the blood pouring out of the neck of one of Durga’s decapitated forms.)

8: Kendua Shanti Sangha

Eighth from the top, again, up against some stiff competition was Kendua Shanti Sangha. Really tough to bring a justification to this, but Kendua Shanti Sangha, in stark contrast to Mitali Kakurgachi and many of the other styles, felt like a relief. A place where you would spend a long and meditative time.

The actual workmanship of the pandal does not have a great deal of finesse. The theme is the Guru Granth Sahib book, in a Gurdwara type form. Almost entirely white, with divine lighting, that offers not only points of focus, but also an ethereal white glow over the entire space. Being thus bathed in soft light the pandal gives you an overwhelming nudge towards silence, in the same way that some churches do. The artist says that he wanted to capture the spirit of a particular mantra (with which I am sadly unfamiliar, but he certainly captured a uniquely different feel). Coming out of the grime and the dust, this pristine holiness acts like a sensorial palate cleanser. Unfortunately, we didn’t manage to catch it at night, so here’s a video from their Facebook page. Feel free to mute the sound, the actual soundscape wasn’t this. https://www.facebook.com/p/Kendua-Shanti-Sangha-Sarbojaninin-Durgotsab-Committee-100069829133741/

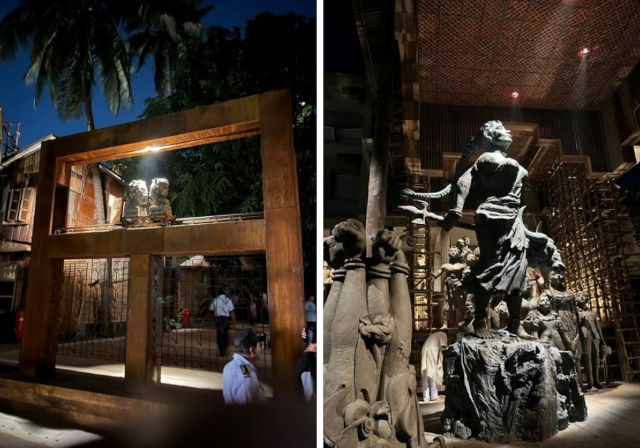

7: Arjunpur Amra Sabai

Seventh up is the first pandal I saw this year, straight from Dum Dum Airport. Arjunpur Amra Sabai has a legacy of winning awards and they did not disappoint. The first of a few pandals that had live performance artists, and the only one that had a timed experience. First, you would be outside, watching a lone man, among the rooftops, on his writing desk stamping out documents. I’m not sure I followed the plot, and what he was supposed to signify, and whether he was the protagonist, the narrator or sutradhar, or a bureaucrat stamping down on creativity, but the man’s dedication to sit there and perform ad nauseam for hours on end is commendable. Thereafter is the ungodly clang of two statue heads banging together (conflict? Clash of intellects? Who knows?) and you move into the inner space.

The inner space uses an under-construction building to add a layer of straw bodies looking onto the amazed children of Durga, who see her triumphant. She looks up into the light, with the realism dripping bull head proudly displayed on the non-stab end of her trishul. Where are her other arms, you ask? Well for some reason they are bound to a pillar, weapons felled. They strangely give a counterpoint to the triumphant figure, and make you feel that you have arrived after the struggle has allowed the vanquisher to emerge victorious despite life’s vicissitudes. It is possible that the entire pandal refers to some story from Bengali lore, but unfortunately I couldn’t for the life of me tell you what it is. I can say, however, that the commitment to round-the-clock performance art is commendable, and the Pratima is dramatic beyond expectation. Also my grave apologies that in some of these photographs, I appear to have been idiotic enough to have my finger covering the lens. Well, that’s what you get with citizen journalism.

6: Naktala Udayan Sangha

Thus we move on to No. 6. Naktala Udayan Sangha has had stunning and similarly themed pandals in the last three years, and this year is no different. They are in fact the location of a relocation camp, of people who migrated from East Bengal. Thus their theme often creates itself. This year too, heartstring-pulling Naktala feature water from East Bengal, bare cupboards, and name plates that show East Bengali addresses and the most stunning of all, commissioned for this pandal, a songscape. Luckily for us the puja committee have put the song in full on YouTube here. Unfortunately I don’t have the ability to give you a good translation, but in essence the song wishes well to everything in Hridaypur (literally translating to place of the heart), and asks telling questions like how do you take something like the smell of soft soil?

On top of ply and cupboards are hand-painted replications of photographs from the time of people who have shifted to Naktala along with bed posts and other furniture. A wooden replica of the affidavit of refugeeism is placed.

And underneath the Pratima in several segmentations, you’ll find various types of soil placed, harkening back to the song.

Rather than being sombre or upsetting, there’s something strangely uplifting about this year’s art. It seems to honour a new life, and be a place full of hope, which is a different way of treating what could easily be portrayed as suffering. Though I will hark back to the previous two Naktala years, which, more than this year, has clobbered us with an emotional sledgehammer.

5: Kashi Bose Lane

Fifth from the top is the hard-hitting, message-driven Kashi Bose Lane. Trigger warnings for girl child trafficking. The first thing you encounter is an American McGee styled doll’s head and hands in a gunny bag.

Walking inside you are not sure what it is meant to represent, and are surrounded by embroidered tapestries of bhadro-looking gentlemen in their dhotis, carrying their umbrellas. It’s only the context of the inside of the pandal that puts this in horrifying perspective. As we pass by signs that say save the children, we realise this pandal is about girl child trafficking.

The next installation has girls on a rotating disk, with apples having replaced their pelvic area. Eerie tongues seem to reach out to them from below, and vultures perched on dining chairs surround them.

The next room has a statue of a child looking at two mirrors in front of her, and the reflections of two bridal beds in front of it. In the centre it says “I don’t want to be Uma”. All around are cages with the clay heads of girls alongside the clay heads of Durga. By now you probably know that Uma is one of the names of Durga, specifically when she left her mother to go to Shiva.

The last room has the Pratimas. At the feet of the Durga Pratima is a child bride. Again, another piece of context is that pre-menstruating girls were (and in some cases still are) part of the ritual to represent Durga during Durga Puja, dressed in exactly the same red sari. Above the Pratima is a child leaping to freedom towards a single window opened up to the skies above. Right, deep breath, it’s over now.

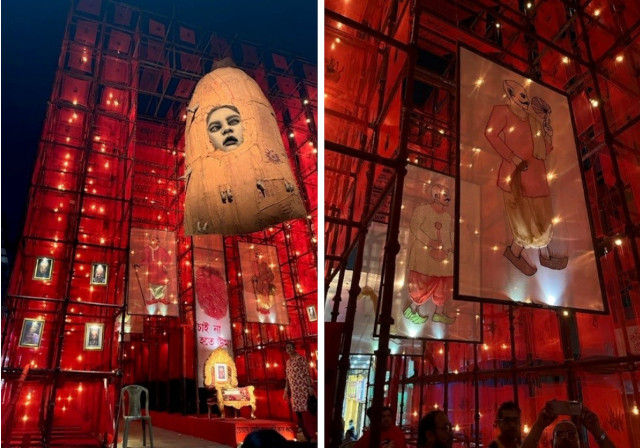

4: Hatibagan Nabin Palli

Fourth up is everyone’s favourite, Hatibagan Nabin Palli. This one commemorates Sukumar Ray’s seminal children’s satire, Abol Tabol, which this year turns 100.

The actual space the installation takes place in, is just a street and a bylane. Actual houses get repainted and integrated into the art. Electric boxes get repurposed into art, carefully placed quotations from the poems become social commentary, and the odd fantastical beast adds the book’s quirk to the entire locale.

It was also the second stunning use of performance art where many actors recreated parts of the book. I wasn’t lucky enough to see them when they were performing, so I’m going to grab a quick video from the net, and hope the person who created the video doesn’t mind.

Lastly you enter a replica of Sukumar Ray’s ancestral home (U. Ray & Sons) and see things like his possessions and his printing press.

The Pratima isn’t a Pratima at all. It is carved wood, which I’m happy for, as a traditional pandal Pratima would have suddenly taken you out of it all. It is four planks, one for Durga, one for the evil demons, one for the children and one small one for Shiva. I wish I had them all in one photograph, but I didn’t manage, so here’s an assembly. I’m not sure what the art style is; it seems like a combination of Indonesian and Toltec wood art, or maybe it’s a printing block made, what do I know? In any case, it feels like it drives a narrative and is child friendly, so it fits in a strange way, into the entire installation. Making it directly in the Abol Tabol style would have cheapened things, so I’m glad they went for this approach.

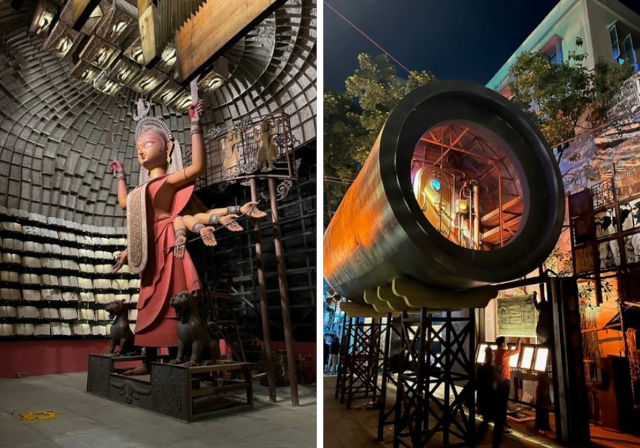

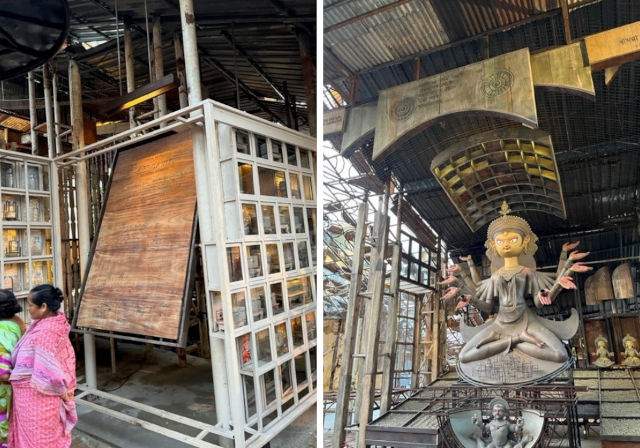

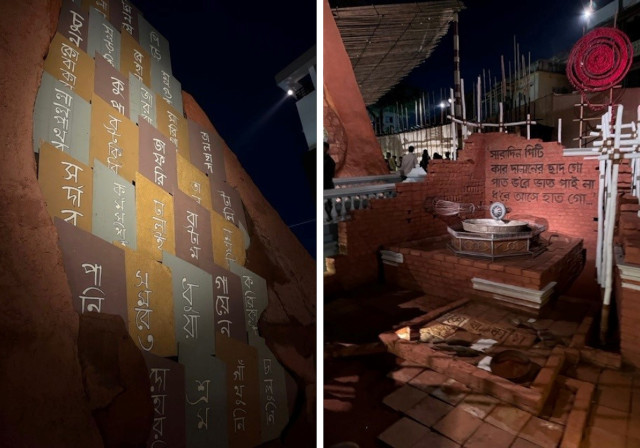

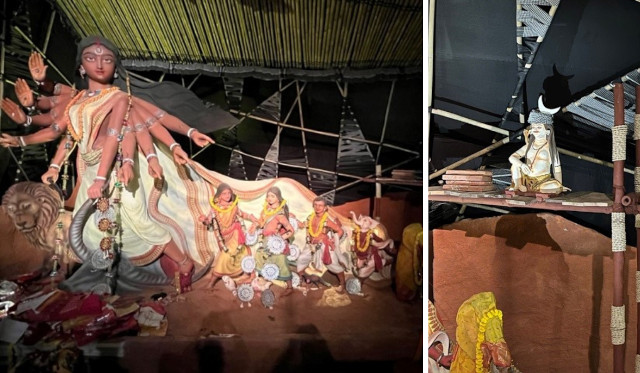

3: Kidderpur 25 Pally

Third from the top is a touching tribute to the lives of construction labourers. Kidderpur 25 Pally speaks from their point of view. Their celestial object (I’m unclear if it’s the sun or the moon) is a simple chapati, rotating with the ticking of a clock. One of the more poetic inscriptions reads, “They are paper flowers (connoting delicacy and effervescence), they have no moon in their eyes (read dreams in their eyes, in the same way in English we would stay “stars in their eyes”). They spend their lives like insects inside the bricks they work with.” Another inscription says, “For the whole day long, whose ceiling are we pounding? We don’t get a full meal. Nor anyone to hold our hand.” Another one of the walls seems like a collection of their vocabulary, that has things like “Concrete”, “Dust”, “Tile”, “Rhythm”, “Work-song”, “Measuring Rod”, “Chalk” alongside words like “Together”.

Their tools of the trade are lovingly displayed, things like cement laying and flattening tools, but I’m surprised also to learn, one of them had a violin and a workers vest and lungi. Later in the installation it shows a worker, hunched over, late at night playing the violin, I assume to keep the other workers in rhythm.

Above the enclosure, before you enter to get to the Pratima, you get a mural of the multitude of Kolkata houses built on the foundation of their labour.

The Pratima herself is a masterwork. Determined, and definitely of the labour class, she points in the direction of what needs to be done. In one of her hands, she holds the bull horn and with another the sheering aruval (a kind of billhook machete), that is a no nonsense, all purpose, tool-cum-weapon. In yet another hand she holds her trishul, not resting on it, but in the same casual way that you would hold a lathi in the farmland. Ironically, Shiv, the husband and farmer, sits casually watching all this alongside.

Apart from the evocative subject choice, an aspect that most of us take absolutely for granted, the men and women who make the houses we live and work in, I particularly like the research levels. It’s not thrown at you. It’s clear that the artists who devised this spent time with workers, and understood their psyche, in a way that is only possible when they open up to you to a certain extent. Their woefulness is not exploitatively plaintive I feel; it’s just what working people would say to one another. Ultimately it is a respectful showcase of their universe. And it does so in a way that is revealing some aspect about the life of a people, that I was hitherto not privy to. Yet the lives of a people who are not hidden, but walk among us and shop at the same sabjiwalas as some of us do.

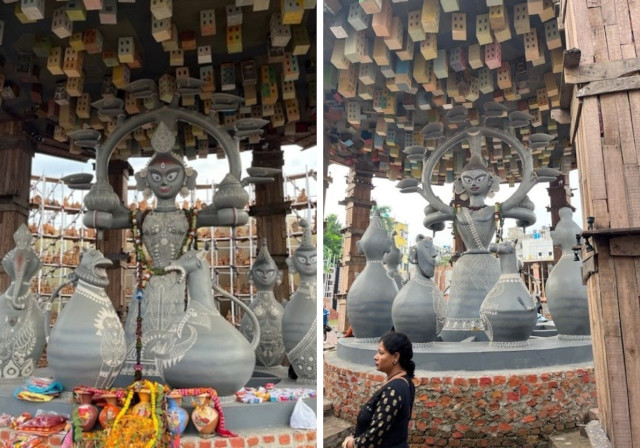

2: Dakshindari Youth

Runner-up this year is a previously unknown (to my family at least) Dakshindari Youth. Unfortunately I visited during the morning, so I don’t have photographs of the absolutely stunning lighting. It’s a tragedy of unknown puja pandals that only a few videos exist of it on the net. I’m going to link the shorter one (again feel free to mute the sound, and I hope the uploaders of the video don’t mind).

This one celebrates terracotta and the terracotta workers. Once again there are parts of pottery and the tools of the trade laid out. But what makes this pandal special is the absolutely overwhelming amount of terracotta art on display. As you enter, of course, is the Kolkata bhar, the tea cup that we all know and love. But it’s displayed and lit very intelligently, in that it looks not like a pile of rubble, but a seascape of tea cups (my own photos, shot by the harsh and unforgiving light of the day, do not do it justice).

You pass by a terracotta city and see the display of the tools of the trade. And of course, you pass by a couple of large kilns that serve to harden the clay.

I’ll get to the Pratima in a bit, but around and behind the Pratima are hundreds and thousands of terracotta sculptures. And they’re not of a rubbish standard either. All of them different and wonderfully lit (look at the video instead of what I’ve got photographed, my photos just show the sheer scale).

The Pratima in fact has two sides. The front has Durga, with her lion facing up against the bull-form of Mahishasura, and the back of Durga being, in fact, Shiva (it’s nice that he’s got her back). The white paint work is delicate and the idols themselves take on the form of traditional clay piggy banks, called Mitti Gulaks (I only suspect this, I’m not entirely sure). If you can take a look at the lion painted in white on the lion figure, he’s very evocative. I also like the way that they have depicted Durga’s ten arms. The choice allows it to be stylistic and uncluttered.

1: Tala Prattoy

Finally we reach the top ranking Tala Prattoy. Normally I don’t really follow artists, and I don’t really even register the names of artists (I should, but I rationalise it by thinking it helps me stay neutral). But over the years Sushanta Paul has carved out a distinct style for himself in his corner of the Durga Puja Market. So pervasive and preeminent is his style, that it has copies in several other pandals (beaten metal seemed to be a running theme this year) and yet, like Anish Kapoor, his hand is visibly distinct.

Once again he is commissioned by Tala Prattoy. It is an utterly resplendent, larger-than-life, serene and transcendent doll-house beaten-metal delicate iron work version of an ancestral home. It comes complete with four or five foot tall pullable drawers that open to reveal more of the house.

There is a phrase about some films that says every frame is a painting, and this artwork is exactly that. Every conceivable photograph that you can take inside the pandal looks jaw-droppingly stunning, while simultaneously, every part can also work as a sublime selfie back-drop, perfectly framing someone who may be dressed for puja (sadly we were dressed for comfort and walking, but you’ll get pictures of my trying anyway).

In other parts of the house there’s a library, full of real books and what appears to be Sushanta Pauls’ study, replete with family photographs. A beautifully lit dining room is part of another area. The architectural detail is absolutely stunning and the attentiveness to the art is indelibly prepossessing. I’ll leave you with a video from Tala Prattoy’s YouTube channel (little long but it will give you a complete flavour, and also invite you to visit their website, if only to impress upon you how professional and tasteful their entire set up is).

That’s a wrap from me this year. I would invite you to comment with your reactions and disagreements. I had a particularly excruciating time trying to get the ranking right. In fact, at various iterations in the evolution of this listicle, as the ten days passed, two pandals (Chetla Agrani and Chorbagan) were as high as No. 2, before being dropped from the list entirely. I do feel particularly distressed about the pandals I didn’t manage to visit, because my high desire for fairness in these matters makes me feel I’ve done them a disservice by not giving them a chance.

Still, there will be next year and next year and the year after that. The tumultuous ride from planning to pitching, to agreeing upon a vision, to executing it must be manic. And I at least, to whatever extent is possible, plan to be there for the ride.