[Andheri Station, one of the busiest transit points in Mumbai for both local and long distance commuters. This is also one of the places where colleagues, friends, lovers and sales people meet to discuss targets for the day. What else do you do in a city that offers no private spaces? Photograph by Slaask under Creative Commons]

I don’t know what this story is intended to be about. Is it about the fact that India has so many young people whom it doesn’t know what to do about? Or is it about the lack of regulations that govern how our businesses are run? For that matter, is it about an overworked government machinery that needs help desperately—and not the blame it is used to being apportioned? In any which case, I do not intend to make any conclusions.

I only ask that you spare some time and attention to an episode that played out over the last two days which I was witness to and share your thoughts. A basic understanding of Hindi will be handy, so that you may comprehend the audio that accompanies this piece.

So, the other day, I received a routine junk call from a Delhi-based number. But the man at the other end of the line didn’t start with the usual “Sir, are you looking for a loan?” spiel.

Instead, he asked: “Sir, I can offer you a loan at 4.99%. Interested?” He got my attention.

How could he possibly offer me a loan at 4.99% I wondered? “If I take a loan from you at that rate and deposit it in my Savings Bank account, I’ll get double the interest rate. What’s the catch?” I asked of him.

“Nothing,” he said. “I am from the Future Group founded by Kishore Biyani. It’s a two day offer and we’re doing it to attract new clients to whom we can cross sell other products later from our portfolio,” he said, sounding rather earnest.

Having spent two decades in business journalism, I know if something sounds too good to be true, it can’t be true. I ended up engaging with him in an hour-long conversation.

To cut a long story short, the sum and substance of his pitch was this.

- He extends a loan to me.

- I buy an insurance policy from him that will contain my name and that of my nominees.

- I hypothecate the document as guarantee to him for as long as the tenure of the loan lasts.

- Assuming I default on the loan, when the insurance matures, he keeps the part of the loan and interest that accrues which is owed to him and refunds the remaining to me. A win-win for all.

- The only caveat is that I don’t have a say in what insurance company to invest in. When I quizzed him hard, apparently, at this point in time, HDFC Life offers him the best brokerage rates for getting in clients and he has a vested interest there. When looked at from my perspective, HDFC Life is a reputed brand to go with, all cheques issued by me will be in the insurance company’s name, and there are no hidden charges. But, he filed one more caveat. The loan will be disbursed only after the mandated by IRDA Free-Look Period.

- To make it sweeter still, if I was willing to pay a higher premium and go in for a larger policy, he could offer an interest-free loan because he’d make money off the brokerage. He explained the math to me. But it’s too subtle and I don’t intend to go into the nuances here. But I must add one minor detail. For a loan of Rs 5 lakh that I asked for, he said, I’d have the pay the first year’s premium totalling Rs 50,000 in full. After that, it was up to me whether to pay monthly, quarterly or annually.

- To make it sound authentic, he reeled off my PAN card number, home address, date of birth, and Aadhaar card number. Curiosity compelled me to ask him if he knew what my CIBIL Score was. He said he knows, the rules don’t permit him, but he’ll make an exception just this once and told me that as well. It matched what I know. In hindsight, I now know all of my personal data has been compromised. That I am stunned is another matter altogether. I have made sure the matter will be investigated—where did all of my details leak out from? What is to stop somebody from impersonating me now? But that is the subject of another story altogether.

- And finally, I told him I have a medical condition and that it is entirely possible the insurance company may reject my claim. To which he promptly told me not to bother about that. Because they have links that can subvert the system and my policy will come through. “The Future Group will handle all of that,” he assured me.

Like I said earlier, it sounded too good to be true. Just to be sure, I asked which portfolio company from the Future Group is offering this deal. “Future Finance,” he said. My eyes blinked for a moment. There is no such entity. The only company in the financial services space Future Group has some association with is Future Capital which is now Capital First and is now run by a different management.

Just that I may be sure, I called up Dipayan Baishya who works with Biyani and co-authored It Happened in India. He told me not to fall for it, called in the legal team from the Group and they asked me if I can tag along and play game because they know a scam is being perpetuated under their brand name. And whether I’d be willing to record the conversations, and set up a meeting with policemen in plainclothes in tow. I agreed. What follows is recorded below

Call 1: Call from “Future Group” to confirm if I am indeed interested in the insurance

Call 2: Follow up call explaining how the scheme works from Future Finance

Call 3: Another follow up call from Future Finance because I have some questions (Gets Disconnected)

Call 4: (Reconnects) Tells me what I ought to say on the phone when a representative from HDFC Life calls

A little later, I get a call from Manohar Joshi who claims he is calling from the Vikhroli branch of HDFC Life in Mumbai. He asks me if he can send an executive to pick up my documents. I say yes and alert Baishya and the policemen.

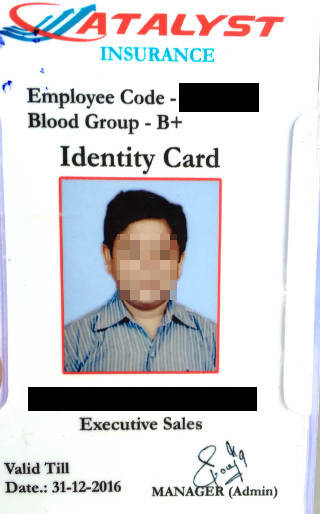

Call 5: I begin to chat with the boy who comes for the document. His identity card says he is a manager. Baishya and plainclothes policemen follow quietly and begin to sit in one by one to listen in.

By the end of it all, it is obvious the executive doesn’t know much. He isn’t from HDFC Life, but from a company called Catalyst Insurance, a Direct Sales Agent (DSA) empanelled with HDFC Life to sell its policies. The boy is taken into custody and to the nearest police station where investigations begin right away. Representatives of HDFC Life are summoned and their legal and risk management teams come in as well.

[At Meghwadi Police Station where the employee is being questioned]

Investigations reveal the company is empanelled with the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (IRDA) to represent insurance companies and HDFC Life is one of its prominent clients. The other one is Bharti Axa. HDFC Life’s legal team does not deny it. The police station traces Joshi down and asks him to come to the place right away. Catalyst turns out to be a Delhi-based firm and the police get in touch with their counterparts in Delhi who swing into action. By now, what is happening is obvious.

All of the calls have originated from its call centres. All of the landline numbers I submit to the police turn out to be fake. They have been routed through the internet. Fortunately, I had tagged along and some of them had shared their cell phone numbers with me. And now that this boy was in custody, his phone was taken away by the police to Meghwadi police station where Inspector Salve takes the case up. He looks into it and starts summoning all of the people at Catalyst. While at it, he tells us scores of people have fallen for the racket. From the boy’s bag, he fishes out a policy form and cheque in favour of HDFC Life for Rs 30,000.

The Human Side

I start speaking to the boy. He is nervous and in tears. It turns out he is from Varanasi and has a bachelor’s degree in the liberal arts from the prestigious Mahatma Gandhi Kashi Vidyapith. But there are no jobs for those who graduate in the liberal arts in Varanasi. Not that there are in Mumbai. So much for all the noise we make about the significance of having an education in the liberal arts.

Poverty drove him to the city. He is just two months into the job, was recruited online, and is paid Rs 10,000 a month to verify documents, pick them up, and deliver them to Joshi. By now he is sobbing and even the policemen feel sorry for him. They offer him a meal and ask him to chill.

[There is nothing romantic about the kind of street food they eat. It is greasy, made in unhygienic conditions, unhealthy in the long run, and all it can do is fill your stomach when you've run out of food from home. Photograph courtesy Dandelion Kitchen]

Under initial questioning he told them he doesn’t know where the office is; it turns out he wasn’t lying. He keeps moving around the city or just hangs out at home—a rented space in a slum. When a text message gets to his phone from Joshi to go pick up documents and verify them from a certain address, he does that. He is then instructed where to meet Joshi to hand over the documents. Much like this boy, there are a few others who report into Joshi, who issues instructions over text messages.

[This is one of the many dilapidated places where these men share their cramped rooms with at least four or five others of their ilk at the end of a backbreaking day. Photograph: Dharavi Slum by Jon Hurd under Creative Commons]

When all of the day’s documents are picked up, Joshi goes to HDFC Life’s Vikhroli office and hands them over to the officer who scrutinizes and logs them into the system. The police tried to authenticate if the man whom Joshi described as the officer at HDFC Life was indeed on its rolls. It turned out, he is. But on this day, he is on leave and travelling. So he couldn’t be summoned for questioning.

I spoke to Joshi later. He is from a remote hamlet in Uttar Pradesh, is married, has two young girls, is in his thirties and visits his wife and children once a year. He cannot afford anything else because he is paid Rs 15,000 a month and has studied only until Class XII. He’s been two years at the place and he doesn’t do much else other than this and pass the documents on to officers at HDFC Life who process the documents. In spite of being on the job for over two years now, he doesn’t have a clue these insurance policies have been sold on the back of promises that loans will be offered. Before this he used to work at another DSA in the loan recovery department of ICICI Bank. He is close to tears as well. I ask him why he took up this job. “Because it offered a few hundred rupees more,” he said.

Between the both of them, they have no clue what loans have been offered. Like the recordings suggest, all they know is they are doing what they are asked to do. They are young. They are desperate. They are hungry. They need to work. The cops ask me if I want to press charges because I am the one who was being “conned”. The officer though doesn’t say it in as many words. He doesn’t want to. I don’t want to either. Nobody wants to. All of us say no. The policeman lets the boys off. But they go after the big fish at Catalyst.

As I probe the delivery boy further, it turns out, he isn’t the only one like this who doesn’t know where their real offices are. Tonnes of companies like these exist in metros. The desperate ones are looped in and offered jobs. But they have no clue where their real workplaces are. They are given an identity card that they may carry. They meet twice a day. Once in the morning at some public place like a train station or a bus stop to decide the target for the day that has been set by their bosses. And once in the evening to take stock if the targets have been met and hand over whatever documents they have collected.

[Even the holder of the identity card does not know where his office is or who the other people in the organization are, other than Manohar Joshi to whom he delivers the documents in the evenings. But this is his Identity Card that he may use to gain entry. It looks as good as that of any professional entity. It was issued to him on the back of an interview conducted after an “online objective test”.]

This is the point Arun Maira was trying to make on the Demographic Disaster awaiting India when he wrote in this space: “…While India’s working age population increased by 300 million between 1991 and 2013, the economy could employ only 140 million. Now, very large numbers of young people, even when educated and skilled, cannot find decent jobs…. By 2050, another 280 million people will enter the jobs market making India the most “job stressed” country in the world.”

The Business Side

I don’t have anything to add here. Except that the legal teams of Future Group and HDFC Life argue a bit. Future Group contends its name and reputation has been tarnished and it will press for criminal charges. HDFC Life argues all this happened without its knowledge. And then they agree they must come to some kind of settlement. What they agree to and how they come to it, I don’t know right now. All of us share amicable cups of tea though at the police station.

The Overworked Officer

I spent pretty much all my day at the police station. By the end of it, I had a headache and all I wanted was to head home, get a good meal, and sleep. The officer-in-charge was dealing not just with us, but with cases of all kinds. We were one among many. He was calm, collected, didn’t lose his head even once, and I didn’t see him step out for as much as a meal through all of the 8-10 hours I was there.

I asked him when may I come and spend time with him so that I can understand how he copes with pressure of this kind. He laughed. He had gotten to work at 8 pm the previous night. It is 6:30 pm now. He isn’t sure when he’ll go back home. Unlike most other people, he doesn’t get regular days off. He is on call 24/7, 365 days a year.

“Come by when you have time on hand sometime late in the night,” he said smiling. “We’ll talk and have some more chai.”

I walked out telling myself, so much for the tub of crock I think about all the time of getting how to be more productive, efficient and keeping my head in place. These are real people, who deal with real problems, in a very real India, every single day. Who gives a damn about them really?