[By User: (WT-shared) Peirz at wts wikivoyage (Own work) (CC BY-SA 3.0), via Wikimedia Commons]

By Tom Nunlist

In the 1960s and 1970s, the most popular wedding gift in China was a bicycle. By the end of the 1980s, there were 500 million bikes in China and Beijing had gained the title of “Bicycle Kingdom”, with freeway-sized bike lanes accommodating millions of commuters.

Then things began to change. Bike lanes shrank as car lanes grew, bus routes and subway systems underwent massive expansion, taxi cabs became affordable and electric scooters pervasive. The humble bicycle never quite disappeared, but society moved on to bigger things.

But in 2016, a stroke of genius helped the bike stage an unlikely comeback as part of the “sharing economy”. Bikes can now be rented via an app and you can park them anywhere on the street.

Such is the ubiquity, particularly of the two leading companies—Mobike (10 million orange-and-silver bikes) and Ofo (20 million canary-yellow bikes)—that the bicycle can be thought of as the two-wheeled flagship of sharing, spreading the gospel of the business model. In March, Shanghai was the most shared bike-heavy city in China, with 450,000 on the streets.

Since shared bikes hit the streets, the phrase “sharing economy” has gone from buzzword to boom market. But defining the sharing economy can be confusing. Uber and Didi, for example, are often referred to as “sharing economy” companies, but many disagree. The term usually covers businesses that share underutilised assets, like cars or spare rooms—but China’s proliferation of the scheme has muddied the concept. While there are businesses familiar to Westerners—shared offices, cars and rides—there are also ideas that seem a little kooky: shared basketballs and umbrellas.

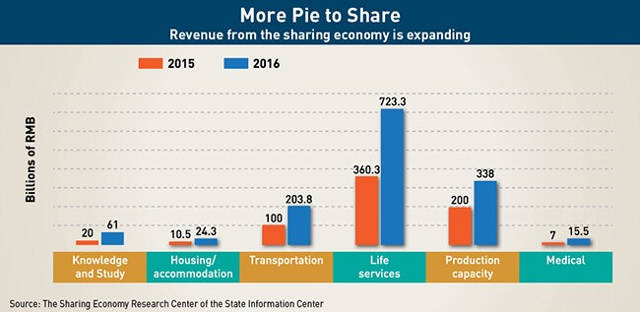

According to China’s State Information Center, transactions in the country’s sharing economy last year were worth more than $500 billion and involved more than 600 million people. The Center estimated that by 2020, the sector could account for 10% of GDP growth. Regardless of the numbers, it is clearly transforming the way people live.

“I think this is an evolution of society,” says Bill Li Wenlei, founder of shared office space MydreamPlus. “As the technology evolves, we will have more areas covered by the shared economy.”

Investors are naturally following the trend. Venture capitalists in China threw $31 billion at startups in 2016, an increase of nearly 20% from the previous year, according to KPMG. While it is unclear what proportion of that went into sharing economy startups, those businesses seemed to steal the show—according to Crunchbase, a database which keeps track of the tech startup industry, Mobike and Ofo have raised more than $2 billion collectively.

But there is a healthy degree of scepticism about whether it can all work. The sharing space is being sustained by hot money and a great deal of official support, or at least rhetoric. What will happen when the excitement dies, as it presumably will?

“I can’t see why some of the services won’t succeed, and won’t keep going,” says Andrew Atkinson, marketing manager at brand consultancy China Skinny in Shanghai. “But I definitely feel some of the business models have not been fleshed out.”

Terms and Limitations

One of the messiest things about the “sharing” space is the blizzard of terms surrounding the phenomenon: sharing economy, access economy, collaborative economy, on-demand economy, freelance economy, gig economy. According to April Rinne, a globe-trotting sharing economy consultant who, among many other things, sits on China’s National Sharing Economy Committee, the public often assumes these are all the same when they are in fact different, although overlapping.

The definitions are fluid even for experts, but a few examples can help define the boundaries. Take Bla Bla Car, the $1.5 billion French ridesharing platform that connects drivers making long trips. Riders contribute to the cost of the trip, but the driver doesn’t earn money, so it is truly shared—although the platform is monetised by taking a small cut. Bla Bla Car meets Rinne’s three primary criteria of a sharing company: utilisation of under-used assets, decentralisation and an element of relationship/community building.

Now take Uber. The overlap with the Bla Bla Car model includes decentralisation and shared use, but there are differences, the most important being that Uber drivers drive to make money. Some surveys find a third of them do it as a full-time job (Uber even offers drivers financing to purchase cars).

Many other sharing economy businesses fall somewhere in between. Airbnb, like Uber, has also become professionalised, but retains a focus on relationships. Shared office spaces are centralised and often professional, but the community building aspect is extremely strong.

The Mobike and Ofo model is different again. The bikes are owned by the companies, so the focus is not on under-utilisation and in practice there is little focus on social interaction. Rinne, however, notes it removes ownership from an object you once had to buy. This is the model of many of the businesses in the recent sharing explosion in China, and it may be spawning yet another term.

“It is really Renting 2.0,” says Oscar Ramos, Program Director at Chinaccelerator, a startup accelerator in Shanghai.

Trail of Disruption

Renting 2.0—or whatever you choose to call it—is now everywhere you look in China, changing city life, upending businesses and sometimes just being in the way. That last factor has become a hallmark of shared bikes, especially as Mobike, Ofo and others compete to outspend each other for market share. The station-less nature that makes them so convenient also makes them inconvenient, as people often park them poorly, or that they tend to pile up in the hundreds at heavily trafficked spots. Some cities have begun wholesale impounding them to clear the way.

It’s the lawlessness of China that makes it possible

But this hints at a reason why sharing businesses have taken off in China: the country’s dynamic nature at street level, both in terms of lifestyle and in testing out new ideas.

“It’s the lawlessness of China that makes it possible,” says Atkinson, observing that if the bikes were better policed, or people more careful about parking them, the convenience factor that makes them work would be eroded. The key innovation, after all, is their “anywhere” nature. “People just get out of the metro and jump on.”

The second factor aiding the growing of sharing business in China is the mobile payments revolution driven by Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat Pay, which allow consumers to painlessly spend even tiny amounts of money by simply scanning a QR code (an advanced barcode). “[The sharing economy] in China would not be what it is without mobile transactions,” says Atkinson.

The rapid adoption of mobile payments in China is driven by the general openness of people to try out new things

The rapid adoption of mobile payments in the past few years is itself driven by a third factor in China, which is the general openness of people to try out new things. “The first thing people think about consumers in China is volume,” says Ramos. “But the best thing they have is an open mind, flexibility and lack of legacy.”

These factors set the stage for the sharing economy invasion currently moving across the spectrum of personal goods. Some seem to be solid ideas. There is a basketball sharing startup, which works as an unmanned station near basketball courts, so you can go shoot hoops even if you didn’t bring your own ball. There’s also a suitcase sharing startup in tightly-packed Hong Kong where owning luggage means finding space in your tiny apartment for a big box you use only occasionally.

Others are less obvious. Several companies have popped up that rent power banks, so that users may charge their mobile phones for a small fee, for example at a bar or restaurant. But the project that has got the most giggles was an umbrella-sharing startup, Sharing E Umbrella. The company lost nearly all its initial 300,000 umbrellas just a few weeks after launching due to holes in the plan—people did what they do with their own umbrellas, left them haplessly at home, the office or on the train.

In innovation, the difference between crazy and brilliant is just so fine that you can never tell the difference

While it is easy to scoff, Ramos points out that these types of failures are a natural part of the business of innovation. “The truth is that there are a lot of inefficiencies in the world, and where these inefficiencies are, we don’t know,” he says. “Airbnb, which is probably the first large example of a sharing economy business, looks super crazy if you think about it. Even the investors that were backing the company weren’t sure it would work.”

Ramos believes all the firms launched so far have identified real problems. Getting caught with a dead phone battery really is a huge pain. And the way people use umbrellas really is wasteful—who doesn’t have a half dozen lying around?

“In innovation, the difference between crazy and brilliant is just so fine that you can never tell the difference,” says Ramos. “You just have to follow the customer.”

Another unexpected idea to gain traction recently is shared toys. There are at least three companies in the space: Wanju Zuzu (Toy Rent Rent), Wan Duoduo (Play More) and Baobei Banjing (Baby Radius). Xie Wenting, a 31-year-old mother in Beijing, uses the latter to provide toys for her toddler. “In my experience the toys are clean,” she says. “RMB 469 ($71) per year is cheap… I recommend it!”

On closer analysis, the concept is a sensible solution to a practical problem: quality toys for children can be expensive and kids quickly outgrow them. Why not use them for a few months and exchange them for new toys?

Hot Money, Big Support

When you have too much money, you solve the problems with money, not creativity

What Ramos does see as a problem is all the investment cash flying around. “A lot of cash kills startups,” he says. “When you have too much money, you solve the problems with money, not creativity.”

Ramos calls out E Umbrella specifically, and CEO Zhao Shuping’s promise to carpet bomb cities with 30 million more umbrellas by the end of the year. Yet, there is still no clear plan to keep them from disappearing yet again.

At the same time, the emergence of the sharing economy has aligned with several of the government’s goals, including finding ways to boost the economy, save resources and reduce pollution. Those attributes have garnered support from the highest levels.

“The country’s sharing economy, enabled by the Internet Plus, has been instrumental in absorbing excess capacity and creating new jobs through its various new business models,” said Premier Li Keqiang at a State Council meeting on the topic in June. “We should give credit to the sharing economy as a reinvigorating force in China’s economic growth.”

Also, innovations like station-less bike sharing are home-grown, at a time when China is hungry to stand out more as a global thought leader. “Any opportunity the government gets to push… something that puts China on the world map in terms of being a leader, it is going to receive a lot of support,” Atkinson says.

All that support has a flipside, in that companies that are not really sharing are trying to elbow in on the buzz in what April Rinne calls “share washing.”

“We have seen a lot of companies adopt sharing economy language when they are not sharing economy at all,” says Rinne. She points to recently launched “shared gym pods” hitting the streets in Beijing. The “gym” consists of a treadmill in a tiny air-conditioned cube parked in a public location. And of course, gyms are already a community-accessed service, which makes the whole thing doubly strange.

Even more amusing is the “shared book store” launched earlier this year in the eastern province of Anhui. Some critics pointed out that it seemed scarcely different from video rental businesses, which disappeared long ago. But that of course ignores the fact a free “book sharing” programme has existed for hundreds of years—it is called the “library.”

One view is that these launches are cynical attempts to cash in on a buzzword. But Wei Wuhui, a popular tech business commentator and lecturer at Jiaotong University in Shanghai, says that Chinese entrepreneurs may just be doing what needs to be done in a moment when the government has seized upon the idea.

“To do business in China, you must heed the call of the Party, the call of the government,” he says.

Share Me the Money

But having the snappy idea and the right slogans in no way guarantees financial success. And in China’s so-called sharing economy, there are few clearly workable business models. For starters, many businesses seem way too cheap. Shared bikes started out at only RMB 1 per half hour, which puts profitability into question given the initial cost of the bikes and upkeep. And the free-for-all market-share battle has devolved at times into a literal free-for-all with companies giving away rides at no cost.

But like other aspects of innovation, it may be a matter of toying with different models until something hits. Atkinson brings up the advertising potential of these companies—already companies are parasitising bike sharing by slapping them with sticker advertisements and tying small business cards to the handlebars. The umbrellas, too, may be monetised this way, he says.

But he says that for some investors, profit may not even be the goal. “I feel like a lot of incredibly wealthy Chinese investors are starting these things because it is cool, and it is a trophy, a pinup sharing brand on the internet of things,” says Atkinson.

Wei Wuhui has a different take on the question of profitability. He says that the most popular of these companies in fact function as proxy battle space for the competing payment systems, Tencent (WeChat Pay) and Alibaba (Alipay). Such was the case with ride-hailing companies Didi Dache, backed by Tencent, and Kuadi Dache, backed by Alibaba, as they each burned hundreds of millions of dollars in competition before finally merging to form Didi Chuxing. Alibaba lost and now Didi uses only WeChat Pay.

“[For them] losing money is really no problem,” says Wei. It’s about dominance in the payment market. Mobike and Ofo, he says, are a continuation of that battle, as they are backed by Tencent and Alibaba respectively.

One consequence of these businesses and the scan-to-pay functionality is the “data-ising” of every user they touch

Only the biggest of the sharing operations fall into this category—basketball and power bank sharing are too niche. But another important consequence of these businesses and the scan-to-pay functionality is what Wei calls the “data-ising” of everything they touch, and every user they touch. That can, for example, be leveraged to serve up advertisements. It’s worth noting that model has long been proven by titans like Facebook.

Permanently Borrowing

Unproven though the business models may be, the concept of “sharing” seems here to stay. Oscar Ramos compares the situation to the Groupon copycat craze that blew up around 2010—the innovative model requires a threshold of customers to commit to purchase before a coupon deal is activated.

At one point, there were hundreds of such companies in China, which led to a predictable meltdown. Fast-forward to 2017 and there are only a few survivors, but they have healthy businesses. That does not dampen Ramos’s enthusiasm. “What is exciting about this whole thing is that we will probably see another [sharing company] that in six months becomes indispensable,” he says. It is impossible to say what that might be until it appears.

For both China and wider world, April Rinne believes that we are at the beginning of a new lifestyle in an age of mass consumer marketing that has, up until now, made ownership something sacred. “I have to say we have barely touched the tip of the iceberg in terms of the kinds of ways we can rethink whether you access something or you own,” says Rinne. In the future “when somebody takes a snapshot of their lifestyle they will see many more things that they access or subscribe to.”

Such a change may be far, far more important in China than anywhere else, simply because of scale. The new “middle class” is still a minority, and it is easy to see how the ascendance of hundreds of millions of more people can create real strain. Ramos notes that the compound where he lives in Shanghai has eight towers of about 40 stories each and no parking. If access to a car is a hallmark of the middle class, where will you put them all?

The sharing economy, he thinks, has an answer, particularly if it ends up looking like Mobike, but for vehicles—that is, by removing actual ownership while at the same time maximising access. “It is a more efficient way to roll out ownership,” he says. “And a faster way to give people a better quality of life.”

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]