[Image from Facebook]

Every moment in business, Peter Thiel wrote right at the beginning of his book Zero to One, “happens only once.” He went on to say, “the next Bill Gates will not build an operating system. The next Larry Page or Sergey Brin won’t make a search engine. And the next Mark Zuckerberg won’t create a social network.”

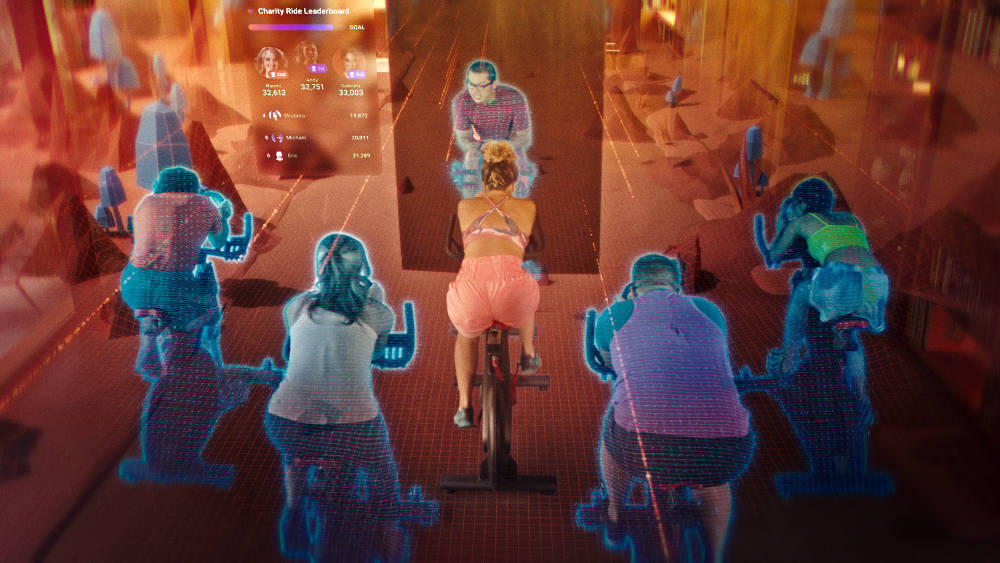

Thiel’s book is about how these iconic founders—Gates, Page, Brin and Zuckerberg—would think about startups and building the future if they were getting into the field today. It doesn’t answer what Zuckerberg would build now, but the Facebook founder himself gave an answer two weeks ago. He would build a metaverse, “a virtual environment where you can be present with people in digital spaces.” He renamed the company Meta, which in Greek means Beyond. The idea itself is not new. The term was first used by Neal Stephenson in his 1992 novel Snow Crash, but the idea has been on the minds of science fiction writers and philosophers for much longer.

For Zuckerberg and Facebook it’s a big bet. “In the coming years, I expect people will transition from seeing us primarily as a social media company to seeing us as a metaverse company,” he told analysts earlier.

Zuckerberg’s choice of words might suggest there is some consensus in the way people look at Facebook. But beyond the fact that people see it as a social media company, there isn’t. The views are divided. And that reflected in how people reacted to the news.

Some believe that the pivot will see the company at the forefront of transforming online identity, gaming, work and communication. Part of this belief comes from Zuckerberg’s success as a founder and leader. A startup founder tweeted, “I don’t like Facebook, but I wouldn’t bet against Zuck.” (The New York Times once quoted Paul Graham, co-founder of Y Combinator, as saying, “I can be tricked by anyone who looks like Mark Zuckerberg,” which Graham might not have said, but the quote’s subsequent popularity indicates Zuckerberg’s formidable reputation in the tech/business community).

Others were critical—either because they thought Meta can’t pull it off (Scott Galloway, professor of marketing at NYU Stern School of Business, wrote, “I just love the fact that 10,000 Facebook employees are driving to work every day to accomplish nothing”), or because they thought Meta can pull it off, and it’s not a good thing. (An early Facebook investor, Roger McNamee, told BBC, “It’s a bad idea and the fact that we are all sitting and looking at this like it’s normal should be alarming everyone.”)

As always the truth is more likely to do a dance between these three points. The reason is threefold. Facebook has already put in a lot of effort into the metaverse. There seems to be some intent to do it right from the start. But, at the same time, the history of the tech industry also shows that even with the best intent and capacity, things don’t always work the way the creators envision.

But one thing is clear. There was no way Zuckerberg—the only founder who is still leading a big tech firm—could have sat on his hands. He had to do something.

1. The same business model that gave Facebook huge scale also gave it huge problems.

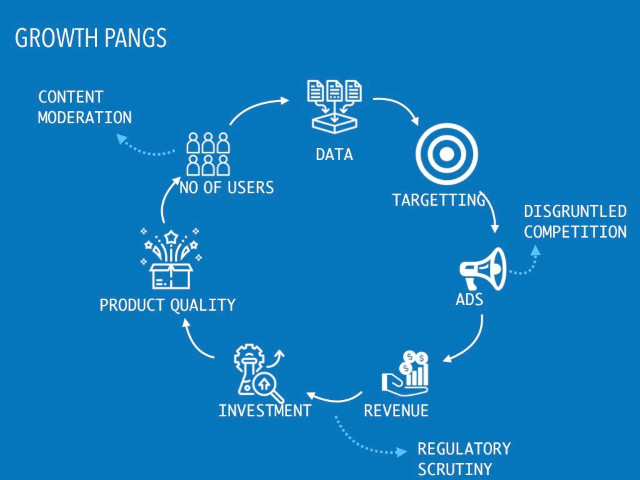

Facebook’s business model was designed for scale, and it got reinforced by the leadership’s obsession with growth. Data is at its core. The more data it collected, the better it could target users, which was exactly what the advertisers wanted. (Facebook’s revenue per user is $8 a quarter, against Twitter’s $4). Ad revenues, which make up 90% of Facebook’s income, poured in. Facebook used the cash to make the product more engaging, more attractive to users (and also buy up Instagram and WhatsApp, companies that attracted users at scale). More users meant more data, and more data meant better targeting, and the cycle went on.

But the very scale brought it problems. There was more scrutiny from the media. It was mostly because of the impact Facebook was having on society, but also because, at least according to Silicon Valley execs, it was eating into the ad revenues of traditional media companies. Facebook had become their competitor. Facebook’s growing size—and how it used its cash on other platforms was also getting the attention of regulators. Most importantly, its scale made it more and more difficult for the company to control—even monitor—how the platform was being used across the world. There were disturbing reports on its harmful impacts on society, for example in Burma, where it was used to spread hate and divide society. In India, its public policy head Ankhi Das was forced to resign amid criticism that it didn’t do enough to contain hate speech.

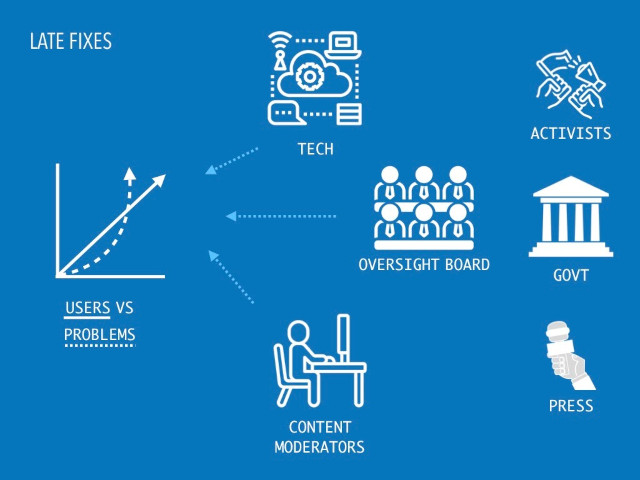

2. Facebook tried fixing these problems, but the fixes haven’t worked very well.

Facebook has used technology to identify and fix problems; it has used human moderators of content. They didn’t work. Tech is not sophisticated enough even in English, forget the plethora of languages used on the platform. Stories of what human moderators went through scrolling over content can be depressing. Recently Facebook set up an oversight board comprising academics, journalists, activists etc, who will act as a supreme court. The impact is not clear yet, and by some accounts it might have come too late. The growing scrutiny by activists, regulators and media is an indication that some of these efforts didn’t play out as planned.

Again, it might come down to Facebook’s own obsession with growth. A story in The Irish Times quoted a former Facebook vice president who said, “Facebook cares about safety ‘to a point’ but ‘errs on the side of growth’.”

A 2016 memo by Andrew Bosworth, a long time executive, and now set to be Meta’s CTO, captured it thus.

We connect people.

That can be good if they make it positive. Maybe someone finds love. Maybe it even saves the life of someone on the brink of suicide.

So we connect more people

That can be bad if they make it negative. Maybe it costs a life by exposing someone to bullies. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools.

And still we connect people.

The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is *de facto* good.

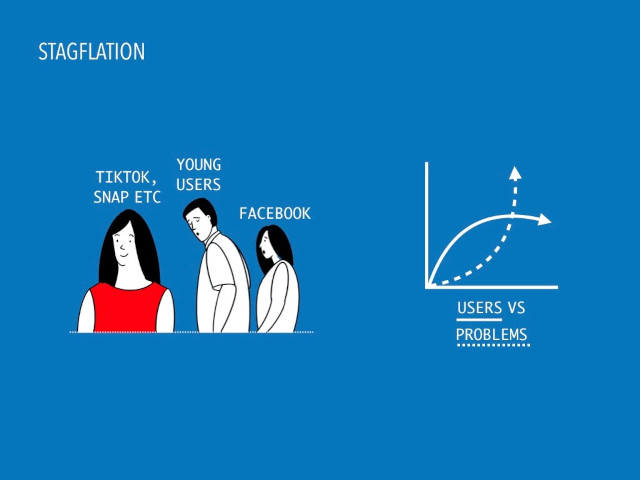

3. Now, that growth itself might be under threat. Its users are aging. The younger crowd is going to other cooler platforms. Facebook is facing a situation where growth stagnates, but problems inflate.

For many the recent WSJ series on Facebook based on the documents shared by whistle-blower Frances Haugen was noteworthy because it showed that Facebook chose profits over safety.

However, it was also noteworthy because it showed that, despite all its revenues (it reported revenues of $29.1 billion in the recent quarter, on track to cross annual revenues of $100 billion) and profits (it made over $10 billion in net profits in the quarter), its executives were worried about its financial health. Younger users don’t use Facebook products and as they get older, don’t sign up for Facebook. It’s facing a flattening curve ahead.

At the same time, the series, and Frances Haugen’s testimony before the US Senate is an example of growing scrutiny of Facebook. As Kevin Roose noted in The New York Times, if the current trend holds in the next few years, Facebook would become “a Boomer-dominated sludge pit filled with cute animal videos and hyperpartisan garbage”.

Not a good position to be in.

4. That’s why when Zuckerberg announced Meta it was seen as an escape hatch.

When Zuckerberg made his presentation two weeks ago, the name change seemed more immediate than all the cool stuff he showed. (Zuckerberg’s presentation was more Elon Musk than Steve Jobs, Alex Webb wrote in Bloomberg, referring to Musk’s tendency to speak about technologies that are far into the future.)

Nick Clegg, Meta's vice president of global affairs (and former Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, under David Cameron), said “We have years until the metaverse we envision is fully realized. This is the start of the journey.”

5. Many successful companies make sure they have a few such “start of the journey” initiatives to sustain growth. Facebook itself had one such transition in 2011-12, when it turned Mobile First.

In The Alchemy of Growth McKinsey consultants explained how better run companies managed sustained growth. They argued that they simultaneously looked at three sets of businesses.

Horizon one represents those core businesses most readily identified with the company name and those that provide the greatest profits and cash flow. Here the focus is on improving performance to maximize the remaining value.

Horizon two encompasses emerging opportunities, including rising entrepreneurial ventures likely to generate substantial profits in the future but that could require considerable investment.

Horizon three contains ideas for profitable growth down the road—for instance, small ventures such as research projects, pilot programs, or minority stakes in new businesses.

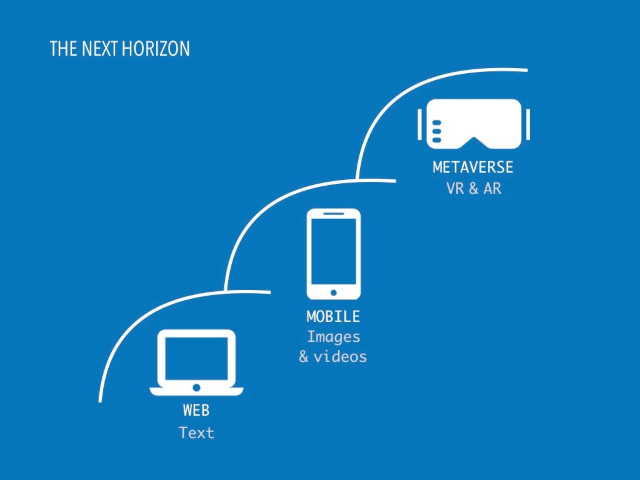

After building a business primarily for connected computers, Facebook transitioned to mobile in 2011 - 2012 when smartphones were picking up. At that time, Zuckerberg took a call that they will focus their attention on building for mobile phones first, and that strategy helped.

It was still playing a catch up game. The iPhone was already around for five years, serious competition to the iPhone was coming up, and whoever could afford it jumped to smartphones even as prices were beginning to come down. The mobile story is far from over. Smartphone sales are picking up in emerging markets, including India. Last year, Facebook invested $5.7 billion in Mukesh Ambani’s Jio, which has huge ambitions for the telecom business.

Metaverse is a bigger bet because the entire industry is right at the beginning of a big wave.

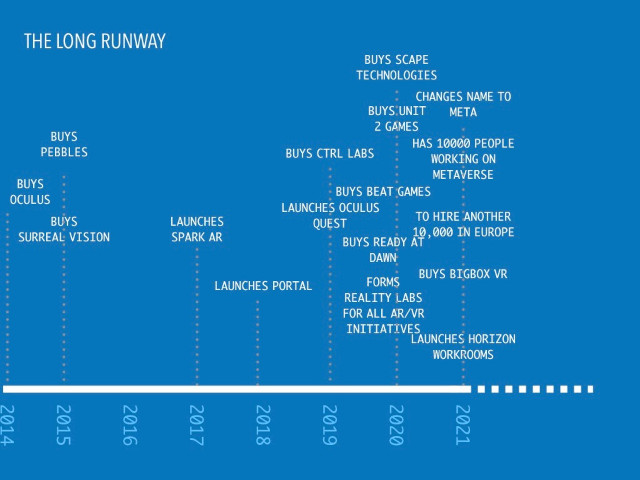

6. In fact, it has been building the capacity over time, starting with the acquisition of Oculus in 2014.

For at least seven to eight years now, Facebook has been building or acquiring technological capabilities that would be key to the metaverse. It started with the acquisition of Oculus, a VR headset maker, and has been building that business consistently over the years. It earns a billion dollars in revenue from the Oculus business now, and is a dominant player in the space. According to IDC, it drove the VR headset market last year. But, it’s not just about Oculus. It has been making a series of acquisitions over the last few years—technologies that will play a major role in the VR/AR world. Its metaverse team has over 10,000 people, and it recently announced that it will hire 10,000 people in Europe.

7. However, the key to Meta’s success as a business will depend on whether and how fast customers adopt it to work, learn, play, build and live.

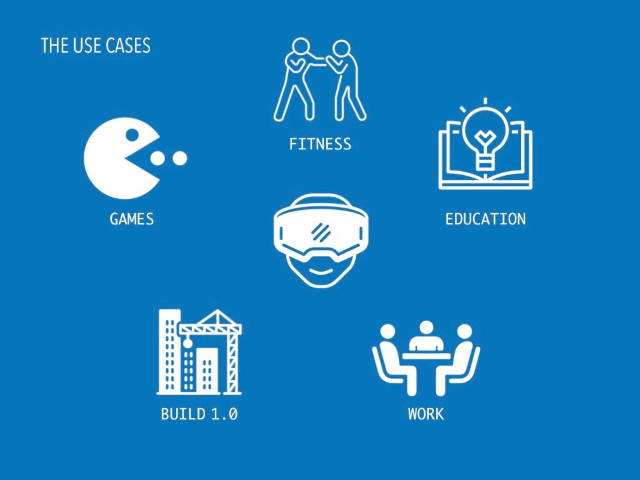

By Zuckerberg’s own reckoning, the immediate use case would be games. Already, VR/AR technologies are used predominantly in the gaming industry. That trend will strengthen, and new uses will emerge. Gaming is closely connected to sports and fitness. One can imagine how having your yoga instructor virtually in your room is better than following her on Zoom. Education has even more exciting possibilities. Again, imagine a professor teaching anatomy while taking you on a virtual tour inside a human body. The key is to remember that at the core of all these is the power of community itself. Investor Balaji Srinivasan often talks about building online communities and then porting them into the real world (a kind of bloggers meet that used to be popular in the early 2000s, or flash mobs, except the relationships are deeper and less transient and what gets built is more substantial).

The argument against all these is not that these might not happen at all—it’s already happening—but whether it will scale.

The argument for this is that the scepticism is mainly due to the fact that we don’t even have version 1.0 of many technologies that we are talking about. However, once VR/AR becomes easier to wear and become more capable, adoption will go up.

There’s another argument against this—which is not that it might not happen—but that we don’t know what the consequences of all these will be when it gets scale. We will come to that shortly.

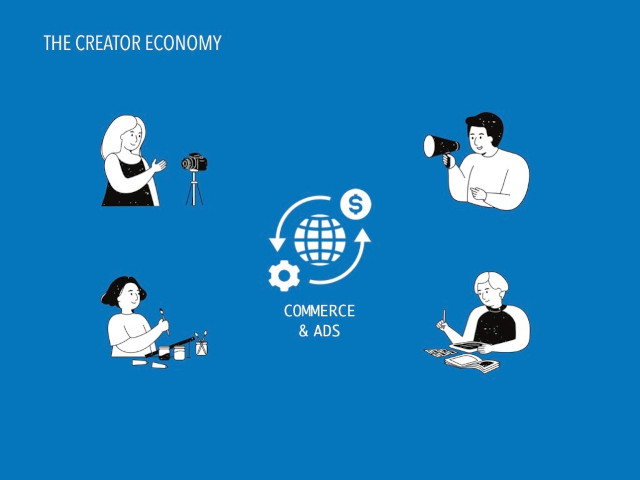

8. Commerce, and therefore ads, will play a key role in the metaverse too.

Community, content and commerce will play a key role in the metaverse. Users will buy digital goods—digital costumes, masks, avatars, interiors, bikes, cars, landscapes—built by creators. Facebook said it will set up a $10 million fund for content creators. The key difference between buying a digital good on say FarmVille and buying one on the metaverse would be you should be able to take it to other platforms. NFTs, or non fungible tokens, and similar technologies are expected to play a key role in this. Zuckerberg has said ads will play a meaningful role in Meta (as against an important role in Facebook). It will be interesting to watch the commissions that these platforms charge for commerce. One of Zuckerberg’s peeves, and one of his motivations for pressing the accelerator on the metaverse, is the high commissions that Apple and Google charge on their platforms. (Oculus charges 30% too, as one Twitter user pointed out).

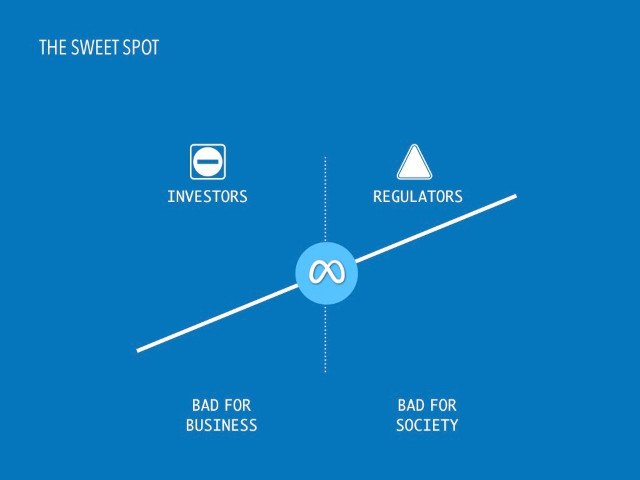

9. The big question is whether Meta can find a sweet spot that gives it scale without exposing it to the problems posed by scale.

As we saw earlier, some of the problems that Facebook faced was because of its scale. Neither Facebook, nor other institutions, seem to have the tools to keep the problems in check. It’s a reason why some regulators have been pushing to break up the company. If scale is indeed the reason, is there a sweet spot where a company can benefit from the economies of scale, and yet escape its diseconomies?

10. The world has changed since the time Zuckerberg created Facebook. Zuckerberg might have changed too.

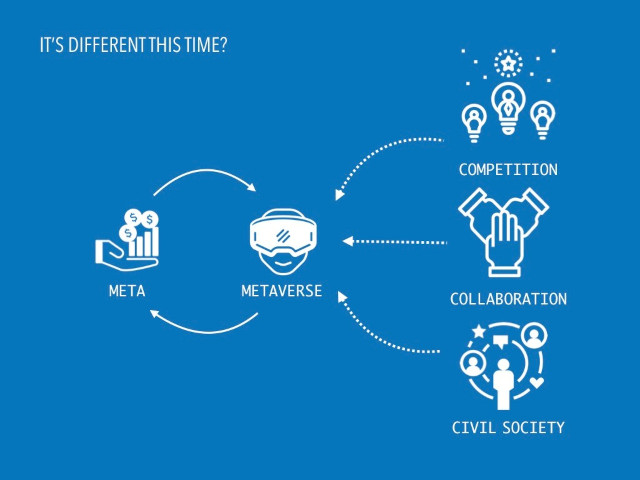

Meta will have to compete not only with the various versions of the metaverse (the definition can include a whole range. Antonio Garcia Martinez recently argued that the metaverse is already firmly in place. “It’s the elective, virtualized reality composed of Twitter, Instagram, and even … Substack”). Microsoft recently announced one for its Team platform. That’s not the only one. Unlike social media or search engines where only one emerged dominant—like Google and Facebook—in the case of the metaverse a more likely scenario is there will be many (or many together will form the metaverse). That also means various companies have to collaborate. While Facebook and Twitter were not taken seriously during their early days, there’s an intense scrutiny of tech these days. Besides, Zuckerberg himself has expressed his intent to take various stakeholders along. Meta has announced a $50 million investment in “global research and program partners to ensure these products are developed responsibly”, and has explicitly stated what the principles would be. Andrew Bosworth, who is leading the metaverse initiatives, and is slated to be the next CTO of the company, is aware of the problems with Facebook’s earlier approach. He told Bloomberg that Facebook “has learned about the consequences technology has on society and thinks it has to have faith that it can do better this time around.”

♦¤♦¤♦¤♦

There’s a reason why Facebook’s metaverse plans have left people hugely divided. It’s still very early in the game, and Facebook might succeed or it might fail. But, it’s important for us to act as if it will succeed for two reasons. Many of the technologies that Zuckerberg spoke about will get built anyway—if not by Facebook, then by other technology firms. And all of that will go into forming the metaverse in which many of us and the coming generations will spend significant time. If we act as if Facebook will fail, we might end up not building the legal, regulatory and other institutions that will help society deal with virtual reality. If we do, there is a possibility that we will be able to reap its benefits while avoiding some of the harms it might cause.

Meta engineers might be designing the devices and writing the code, but the technology will come to life in society.