[Image by Firmbee from Pixabay]

Good morning,

When reporting to write The Aadhaar Effect: Why the World’s Largest Identity Project Matters, at the end of each day, NS Ramnath and I would exchange notes. Our intent was to examine if there were any threads binding the multiple voices we had listened to through the day. Because there was one thing we were convinced about.

All the people we were listening to had a single objective: That the outcomes of their work must impact the maximum number of people.

What most of them disagreed upon was the role of technology. Some argued it is good and others argued it is bad.

Half way through our reporting journey we made our own conclusions.

- Technology is neutral.

- The debates around technology sound loud because it has to do with what someone uses a technology for and how they use it.

While these conversations with Ramnath helped me reconcile the many ideological debates around Project Aadhaar, on personal technology, ironically, I found myself firmly entrenched in the “too much technology is bad” camp. This, even though I consider myself ahead of most people when it comes to embracing technology.

And there was research to support what I believed in.

- Too much screen time can have lasting consequences for young children’s brains (Time Magazine)

- Digital devices can interfere with everything from sleep to creativity (Harvard Medical School)

But since the pandemic struck, it was inevitable screen time goes up. I log in to work remotely. The first thing my kids do upon waking is log in to a device so they can attend school virtually. Most social engagements are now digital. At the start of this year, I would have called this technology addiction. But in the post-Covid world, this behaviour is what keeps us going. Not just that, there is evidence from credible sources that the downsides of technology are over-amplified.

- Screens aren’t as bad for your kids as you think (MIT Technology Review)

- The truth about research on screen time (Dana Foundation)

This compels me to go back to the conclusion Ramnath and I had arrived at when reporting on Project Aadhaar. Technology is neutral. What matters is what we use it for and how we do it.

Now that I’ve had the time to think about it, I figured, I never reduced my consumption of technology. Instead, I’ve adopted it more extensively—but deliberately. Here are my learnings.

Learning #1: Understand Good Tech Use

Let’s start by asking a basic question. What is email intended to do?

Cal Newport, author of Digital Minimalism has it that “A bunch of different things happen when we brought low-friction communication into the workplace. Basically, communication that had zero cost, both in terms of time and energy but also social capital. There’s social capital involved if I'm going to go to your office and knock on your door and negotiate that interaction. All that goes away if it's just email.”

However, he points out, that did not happen. “We began communicating way more than we ever had before, because this tool was there.”

He’s talking about email overload. My limited submission here is that email isn’t bad. It’s just that people use it badly. How is anyone to use it well then? Earlier in June, my colleague Anmol Shrivastava had written about How to make email your superpower. He reclaimed 12 -15 hours of his time each month. That’s over two nights of sleep and amounts to a heck of a lot. May I urge you to go over his learnings? Anmol’s narrative is packed with insights.

Learning #2: No one knows how to work remotely, yet!

One reason I bring up why learning to manage email is important is because I believe as most workplaces finally migrate to WFH and hybrid cultures, they are fumbling. But they are now compelled to migrate. The onus to manage our lives now shifts to us.

To place this in perspective, wrap your head around the fact that the technologies to migrate to remote working have been around for over a decade. Evangelists such as Tim Ferris have made the case in best-sellers such as The 4-Hour Work Week.

Most entities in Silicon Valley started embracing it. Then, Silicon Valley choked beginning with the high flying Marissa Mayer at Yahoo, calling back remote workers in 2013. Every other entity including IBM, AT&T and Google followed and asked people to get back to work. Cal Newport writing in The New Yorker identified it as a “management issue”.

Most managements still haven’t figured out how to migrate to remote working.

But post-Covid, “Some useful innovation is possible on an individual level. As a newly minted remote worker, you may find that demands on your attention are actually more incessant and intrusive than they used to be—a natural consequence when a workplace depends more than ever on phone calls, e-mails, and video conferences,” Newport writes.

So, here’s what I do. And recommend.

1. Engage with what matters on screen. To do that, measure where your time goes. The iPhone gives me a report at the end of every day on what my consumption has been like and what apps I have used the most. Android users can deploy Digital Well Being. For more on how to go about it, here’s a resource.

2. When at work, set all alerts and notifications on mute (particularly WhatsApp, SMS and all other alerts)

3. Have a calendar on when to engage with social media. Because much like email, social media isn’t bad. In fact, it’s a great place. However, it can morph into a place where trolls compete for attention and time. But remember that saying? Never wrestle with pigs. You get dirty. Besides, the pigs enjoy it.

4. Turn off all colours on the phone and put it on grayscale mode. It reduces the urge to look at the device often.

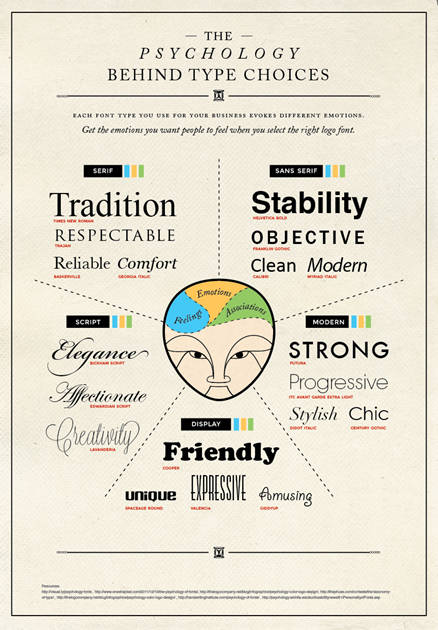

5. Be careful about what fonts you use when making a presentation and sharing on screen. Your focus ought not to be on creating a pretty deck, but getting the outcome you want.

Learning #3: Wake up, keep calm, and move on

Once you start to use tech right and take responsibility for yourself, what will you do with the time you gain?

Meditation is something Anmol and I find much solace in. Technology has helped us with it. He settled on the Calm App while I use Waking Up, created by Sam Harris. We wrote about why we did so earlier in August.

Since then, I’ve invested in an Apple Watch as well because I am on the iOS ecosystem. Android users have other options to choose from such as Samsung Galaxy, Amazfit and Garmin Vivoactive among many others. I cannot speak for the Android ecosystem—but can certainly say money invested in the Apple Watch was money well spent.

Because it is tightly integrated with my Macbook Air and iPhone, I don’t need to access either of these devices as often as I used to for tasks such as dictating notes, keeping track of the calendar, and as a GPS, among other things.

But what matters most is that since the time I have got it, the device allows me track of my health vitals. I now know that I perform best on days when I have slept in excess of 6:30 hours with my average heart rate of 50-52. I like how it reminds me to breathe. And when training, I can pace myself with runners in other parts of the country—that’s a huge bonus.

Does this count for screen time? Yes. To that extent, it’s bad technology.

Does it aid my life? Yes. When looked at from that perspective, it’s good technology.

So, allow me to repeat this: Technology is neutral. How it is deployed is what makes it good or bad.

Changes in the White House

(Via WhatsApp)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy. Head over to our our Slack channel.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon links in this article.