[Photo by Edu Lauton on Unsplash]

Good morning,

Imagine you get into a time machine, and go exactly one year back. There, you see your former self and tell them about the pandemic, lockdowns, work from home and everything that hit us in 2020. You then ask them, ‘How do you think you would feel living in such times?’

Any guesses?

Jonathan Haidt, in The Happiness Hypothesis, gives some hint of what that answer could have been.

He writes: “If I gave you ten seconds to name the very best and very worst things that could ever happen to you, you might well come up with these: winning a 20-million-dollar lottery jackpot and becoming paralyzed from the neck down. Winning the lottery would bring freedom from so many cares and limitations; it would enable you to pursue your dreams, help others, and live in comfort, so it ought to bring long-lasting happiness rather than one serving of dopamine. Losing the use of your body, on the other hand, would bring more limitations than life in prison. You'd have to give up on nearly all your goals and dreams, forget about sex, and depend on other people for help with eating and bathroom functions. Many people think they would rather be dead than paraplegic. But they are mistaken.

“Of course, it's better to win the lottery than to break your neck, but not by as much as you'd think. Because whatever happens, you're likely to adapt to it, but you don't realize up front that you will. We are bad at ‘affective forecasting,’ that is, predicting how we'll feel in the future. We grossly overestimate the intensity and the duration of our emotional reactions. Within a year, lottery winners and paraplegics have both (on average) returned most of the way to their baseline levels of happiness. The lottery winner buys a new house and a new car, quits her boring job, and eats better food. She gets a kick out of the contrast with her former life, but within a few months the contrast blurs and the pleasure fades. The human mind is extraordinarily sensitive to changes in conditions, but not so sensitive to absolute levels. The winner's pleasure comes from rising in wealth, not from standing still at a high level, and after a few months the new comforts have become the new baseline of daily life. The winner takes them for granted and has no way to rise any further. Even worse: The money might damage her relationships.”

In this issue

- Why RBI needs a more integrated policy

- How to think about how the world works

- How to square a circle

Have a great day!

Why RBI needs a more integrated policy

Ananth Narayan, professor of finance at SPJIMR, argues that the mandate of India’s central bank should not be restricted to inflation targeting alone, but to take a cohesive approach addressing growth, external balance, financial stability, etc.

“Our current flexible inflation targeting framework attempts to keep it simple, and ends up being acutely simplistic. At best, it might have served as a rule-based carrot and stick that would goad the government to pursue prudent policies. Through the pandemic, however, as the inadequacies became obvious, we have moved to paying lip-service to inflation targeting, while pursuing a de facto and fairly opaque integrated policy framework. Over time, the current status quo is neither sustainable nor desirable.”

“Our current flexible inflation targeting framework attempts to keep it simple, and ends up being acutely simplistic”

Consider some of the challenges. He writes: “While recent recovery is gratifying, our economy is battle scarred, weak, and needs delicate handling. Our central and state governments will have little choice but to continue with large fiscal deficits. Including off-balance sheet expenditures and delayed payments, the combined fiscal deficit this year could well exceed 14% of GDP. Yet, our governments may need to spend even more, and channel funds into productive investments into infrastructure, healthcare, education and nutrition. In the midst of all this, we have seen strong foreign currency inflows, particularly into our equity markets.”

Prof Ananth offers an integrated policy mix in his piece.

Dig Deeper

How to think about how the world works

“I am here to tell you that the reason so much of the world seems incomprehensible is that it is incomprehensible,” is how Tim Maughan's essay on the world we live in now begins. He goes on to argue, the world has become too complex for us humans to manage; and that much of our lives now exist on a network that has acquired a life of its own and we don’t understand fully.

“It’s tempting to think of these networks as huge organisms, with tentacles spanning the globe that touch everything and interlink with one another, but I’m not sure the metaphor is apt.”

He writes: “YouTube users upload more than 500 hours of video every minute—which works out as 82.2 years of video uploaded to YouTube every day. As of June 30, 2020, there are over 2.7 billion monthly active Facebook users, with 1.79 billion people on average logging on daily. Each day, 500 million tweets are sent—or 6,000 tweets every second, with a day’s worth of tweets filling a 10-million-page book. Every day, 65 billion messages are sent on WhatsApp. By 2025, it’s estimated that 463 million terabytes of data will be created each day—the equivalent of 212,765,957 DVDs.”

“So, what we’ve ended up with is a civilization built on the constant flow of physical goods, capital, and data, and the networks we’ve built to manage those flows in the most efficient ways have become so vast and complex that they’re now beyond the scale of any single (and, arguably, any group or team of) human understanding them. It’s tempting to think of these networks as huge organisms, with tentacles spanning the globe that touch everything and interlink with one another, but I’m not sure the metaphor is apt. An organism suggests some form of centralized intelligence, a nervous system with a brain at its center, processing data through feedback loops and making decisions. But the reality with these networks is much closer to the concept of distributed intelligence or distributed knowledge, where many different agents with limited information beyond their immediate environment interact in ways that lead to decision-making, often without them even knowing that’s what they’re doing.”

That he has a point was made painfully obvious when Google suffered an outage earlier this week.

Dig Deeper:

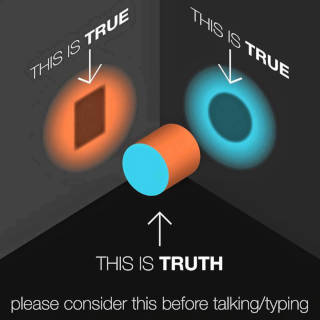

How to square a circle

(Via WhatsApp)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy. Head over to our our Slack channel.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon links in this article.)