[Photo by Jonathan Petersson on Unsplash]

In The Drunkard’s Walk, Leonard Mlodinow, a theoretical physicist, takes us through some studies that show why a sense of control is key to our lives.

He writes, “People like to exercise control over their environment, which is why many of the same people who drive a car after consuming half a bottle of scotch will freak out if the aeroplane they are on experiences minor turbulence. Our desire to control events is not without purpose, for a sense of personal control is integral to our self-concept and sense of self-esteem. In fact, one of the most beneficial things we can do for ourselves is to look for ways to exercise control over our lives—or at least to look for ways that help us feel that we do. The psychologist Bruno Bettelheim observed, for instance, that survival in Nazi concentration camps ‘depended on one’s ability to arrange to preserve some areas of independent action, to keep control of some important aspects of one's life despite an environment that seemed overwhelming.’”

Mlodinow goes on to cite an interesting study by Harvard psychologist Ellen Langer. “Years ago, when she was at Yale, Langer and a collaborator studied the effect of the feeling of control on elderly nursing home patients. One group was told they could decide how their rooms would be arranged and were allowed to choose a plant to care for. Another group had their rooms set up for them and a plant chosen and tended to for them. Within weeks the group that exercised control over their environment achieved higher scores on a predesigned measure of well-being. Disturbingly, eighteen months later a follow-up study shocked researchers: the group that was not given control experienced a death rate of 30 percent, whereas the group that was given control experienced a death rate of only 15 percent.”

Mlodinow’s larger point, however, is not that we should all develop a sense of control. It’s that this need to have control comes in the way of recognizing the role randomness plays in our lives. As a result, we end up having an illusion of control. He points out that this illusion is enhanced in the financial, sports, and especially, business situations.

The antidote to this tendency is not that difficult. Because randomness plays such a big role, it can give us as many victories as defeats. And sometimes, we only have to take stock of both, and “learn to spend as much time looking for evidence that we are wrong as we spend searching for reasons we are correct.”

Note: We are taking a year-end break starting December 24. You won’t get the FF Daily newsletters from December 25, 2020, till January 3, 2021.

We will be back with a great lineup of stories and conversations from January 4, 2021.

In this issue

- The difference between 1991 and 2000

- Why you should start playing chess

- The logic of evolution

Have a great week ahead.

The difference between 1991 and 2000

Even as farmers continue to protest against the farm bill, many economists and economic commentators say that tough reforms will always be met with resistance, and the government must stand firm—just as India passed the economic reforms in 1991, against the protests by the ‘Bombay Club’ of industrialists. However, Arun Maira, in a column in The Hindu points out why the agri reforms of September 2020 are different from the economic reforms of 1991. In short, it’s not just the purpose, the process also matters.

“India’s policymakers must improve their expertise in solving complex, multi-disciplinary problems.”

He writes: “The immediate beneficiaries of the 1991 reforms were all Indian consumers, rich and poor, who would benefit from access to better quality products from around the world. The principal opponents of the reforms were a few large industrialists whose products citizens were not satisfied with. Governments have more power over a few industrialists than they have over the masses.

“With a stroke of the pen, policies could be changed in the early 1990s, the immediate benefits of which were clear to the masses. Hundreds of millions of citizens who hope to be beneficiaries of the ‘big ticket’ reforms, in agriculture, and in industry too, now want to earn better incomes, to earn enough to buy all the good stuff they have begun to aspire for, and even to make both ends meet. They cannot see how the bold reforms being pushed through will result in improvement of their incomes. A trickle down is promised. When will that ever happen, they ask?

“The 1991 reforms changed industrial licensing and trade policies—both subjects of the Union government. ‘Factor market’ reforms, in land, agriculture, and labour regulations, which are necessary to realise the full benefits of the 1991 reforms are State subjects in which States have jurisdiction too, and with good reason. They affect the lives of people on the ground, and differently, around the country. Therefore, the Central government, no matter how strong it is, must not force these reforms onto the States.”

Dig Deeper

Why you should start playing chess

If you watched The Queen’s Gambit and want to dust up your old chess board, as many seem to have done, there is another reason to continue playing it. The reason is concentration, according to Jonathan Rowson, co-founder of Perspectiva, a research institute in London.

He writes: “In his Utopian novel Island (1962), Aldous Huxley depicts ‘reminder birds’ called Mynahs who fly around periodically saying: ‘Attention!’ and ‘Here and now!’ to help bring the inhabitants back to themselves and the present moment. However, if Mynahs were to be released into London, New York, Delhi or Beijing today, it’s not clear what we would be asked to pay attention to or for. Today’s Mynahs are smartphone notifications, which seduce us through our weakness for novelty and coerce us through our fear of missing out, as ubiquitous advertisers, in league with psychographic profilers, harvest our attention as a commodity. Our problem today is not that we don’t or can’t pay attention, but that the systems and structures of society oblige us to pay attention so frequently and fleetingly that we cannot in fact concentrate. Lacking an ability to concentrate, it’s a struggle to construct and maintain a coherent and autonomous sense of self, which leaves us at the mercy of digital, commercial and political puppeteers. Without concentration, we are not free.”

What to do about it? Play chess. Rowson writes: “Any skilled endeavour entails concentration, but chess is unusual in requiring that we concentrate not for a few minutes at a time, but for several hours at a time, within tournaments, for days at a time, and within careers, for years at a time. Concentration is the sine qua non of the chess experience.”

Dig Deeper

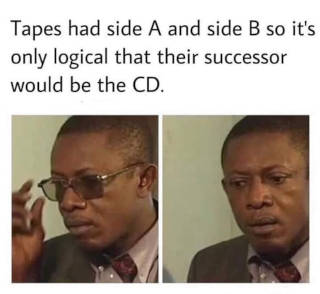

The logic of evolution

(Via WhatsApp)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy. Head over to our our Slack channel.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)