[Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

Good morning

What is well known is our bias to specialize. But this bias of ours often misses the larger point on how all things are interconnected. This is something that emerges through the pages of Walter Isaacson’s most recent book, The Code Breaker, a biography of the American biochemist Jennifer Doundna. This narrative documents the history of gene editing until now and the arc covers characters such as James Watson, who were pioneers in the domain.

“His passion growing up was bird-watching, and when he won three war bonds on the radio show Quiz Kids he used them to buy a pair of Bausch and Lomb binoculars… At the University of Chicago, which he entered at fifteen, he planned to indulge his love of birds, and his aversion to chemistry, by becoming an ornithologist.” Who would have imagined that?

“But in his senior year he read a review of What Is Life?, in which the quantum physicist Erwin Schrodinger turned his attention to biology to argue that discovering the molecular structures of a gene would show how it hands down hereditary information through generations… Watson checked the book out of the library the next morning and was thenceforth obsessed with understanding the gene.” However, Watson was rejected by Caltech and Harvard actually declined to offer him a stipend. That is how he landed at Indian University that was having trouble finding talent.

It was here that he found his PhD advisor, an Italian immigrant, Salvador Luria, who had latched on to study “phages” or bacteria-eaters. But this would mean an understanding of chemistry. So, Luria “helped Watson get a postdoctoral fellowship to study the subject in Copenhagen.” Once Watson got there though, it wouldn’t be too long before he got “Bored and unable to understand the mumbling chemist who was supervising his studies, Watson took a break from Copenhagen in the spring of 1951 to attend a meeting in Naples on the molecules found in living cells. Most of the presentations went over his head, but he found himself fascinated by a lecture by Maurice Wilkins, a biochemist at King’s College London.

“‘Suddenly I was excited about chemistry,’ Watson recalled. ‘I knew that genes could crystallize; hence they must have a regular structure that could be solved in a straightforward fashion.’”

The budding ornithologist would go on to study chemistry and then make landmark breakthroughs in genetics because he had read a paper on biology by a quantum physicist.

Think about it!

In this issue

- What the media won’t tell you

- How the Chinese media works

- When connectivity is poor

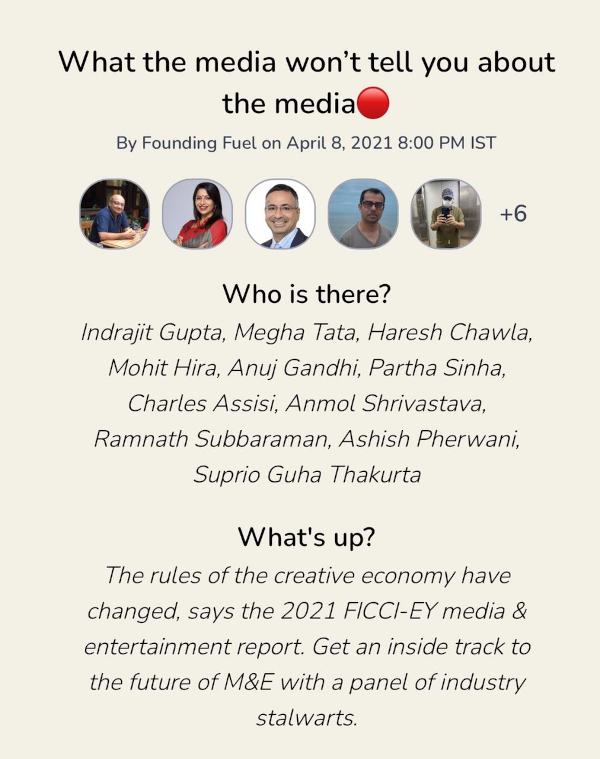

What the media won’t tell you

Like we shared with you yesterday, between 8 and 9:30 PM this evening, we have carved out time to ensure we join the Founding Fuel Room on Clubhouse. We’ll be engaging in a conversation on the state of the media and entertainment businesses. The immediate trigger: a recent report by EY and FICCI on how the entire sector is in the throes of a reboot.

Ashish Pherwani, lead author and EY’s partner for media and entertainment, will be in the room with veterans such as Haresh Chawla, Partha Sinha, Suprio Guha Thakurta, Megha Tata, Anuj Gandhi and Mohit Hira, to discuss the issues this report raises—and what they portend for the future. It promises to be exciting and we’d urge you to join in live.

How Chinese media works

In an interview with The Wire China, Maria Repnikova, an assistant professor in Global Communication at Georgia State University and the author of Media Politics in China: Improvising Power Under Authoritarianism, offers some interesting insights into how Chinese media operates. The following extract is on why Chinese media strategy hasn’t worked well with an international audience.

“This journalistic style is domestically-geared, and it doesn’t really work with external audiences.”

Repnikova says: “I think here we need to talk more broadly about why China’s global media push has thus far produced only mixed results. Empirical survey work in different parts of the world has shown that, indeed, this kind of content is not very appealing. Part of the lack of appeal is that foreign viewers know it’s produced by the CCP. There’s a legitimacy factor: if the audience outside China doesn’t think Chinese state media is fair or objective or independent, their first instinct is to disbelieve whatever they’re shown.

“There’s also clearly a problem with the content itself. Media schools in China pride themselves on practicing ‘constructive’ journalism. By this, they mean positive storytelling: good stories, focus on solutions rather than problems, and so forth. The whole storytelling agenda of Chinese propaganda for foreign audiences carries a constructive tone. That means that many negative stories are not discussed at all. That’s not very exciting for the audiences. Rather than responding to current events, they hew to the same narratives, the same stock characters, the same ideas, over and over. This journalistic style is domestically-geared, and it doesn’t really work with external audiences.”

Some of the media practices in China also carry lessons for global media. Repnikova observes: “I’ve also found that Chinese state news agencies don’t study extensively the public’s reactions to their reports. When they self-evaluate, they usually emphasize quantity versus quality. They ask questions like: how many reports do we put out? How many retweets do the posts get? How many physical copies of China Daily are being inserted into foreign newspapers? What they don’t ask is whether these inserts are being read or just tossed out. I suspect this won’t change in the short term.”

Dig deeper

Still curious?

- Rishikesha T Krishnan says Henry Paulson's book Dealing with China offers a comprehensive account of China's economic challenges, political structure and strategic concerns. Read Understanding China: Insights from Henry Paulson's book - Dealing with China

- Journalists need to be heard to be able to convey truths. But social media has dumbed down public discourse and made it difficult for reflective commentators to be heard, writes Arun Maira. Read: How the media has let down democracy

- Post FT’s sale to Nikkei, there's every chance that the global business daily will expand its presence in Asia. Its market entry in India could depend on whether its new Japanese owner presses the right diplomatic buttons, writes Indrajit Gupta. Read: Will Nikkei fuel FT's Asian ambitions?

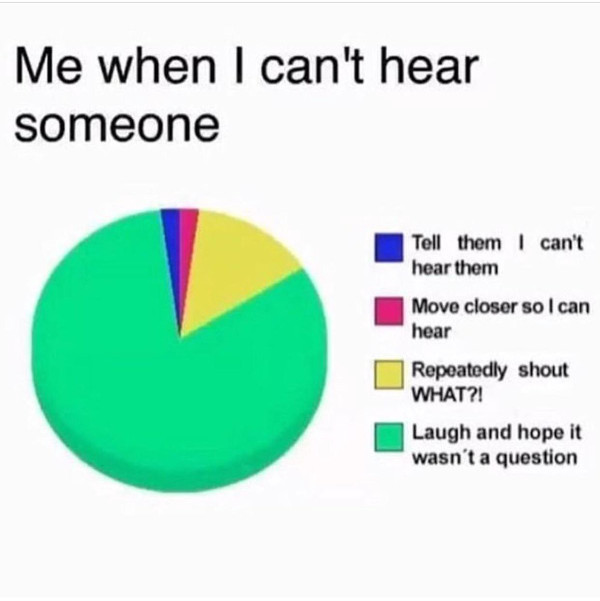

When connectivity is poor

(Via WhatsApp)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)