[Photo by jaikishan patel on Unsplash]

Good morning,

In Strategy Beyond the Hockey Stick, Chris Bradley and his co-authors point out how small design elements—such as opt-in or opt-out in driver’s license application forms—can nudge people into making important decisions such as donating one’s organs. They say the subconscious brain is more powerful than we think, and point to some biases that they have come across in strategy rooms. Here are three from the list.

Halo effect. “Our 6% profit growth last year reflected our decision to continue investing in digital, and, in the face of tough trading conditions, we remained ruthless on costs”—a team giving itself a pat on the back even though the whole market also grew profits by 6%.

Confirmation bias. “We’ve put lots of work into analyzing the reasons why this will work” [but no work into the reasons why it won’t]. “We’ve also heard that our top competitor is exploring this opportunity” [so it must be a good idea]. Good luck with trying to stop the momentum for that project.

Loss aversion. “We don’t want to put our baseline at risk by chasing blue sky ideas. We really appreciate the hard work that’s gone into alternative strategies and new business lines, but ultimately we think the risks outweigh the benefits”—even though the existing baseline might be under threat.

They go on to write: “When you bring together a bunch of people with shared experiences and shared goals, they typically wind up telling themselves stories, generally favourable ones—and we are in the perfect den for these biases to flourish. A study found, for instance, that 80% of executives believed that their product stood out against the competition—and that 8% of customers agreed. This sort of confirmation bias is why people read publications with the same political bent that they have. People may try to challenge themselves, but they really want to nod their heads as their beliefs are confirmed.”

At Founding Fuel, we are very much aware of these cognitive biases, and strive to challenge each other during our conversations. We hope we are challenging your beliefs too every day with our newsletters, stories, podcasts and Masterclasses.

We would love to hear from you.

In this issue

- A history of missed calls

- How to solve problems by cutting down, rather than adding up

- Mark Zuckerberg on WhatsApp

Have a great day ahead, and stay safe!

A history of missed calls

“Give me a missed call” is a uniquely Indian phrase that has a long history. Once upon a time, it was horribly expensive to call someone over the cellular phone in India. It was inevitable Indians deploy their ingenuity. They thought up the idea of missed calls. Atul Bhattarai in an essay describes this phenomenon as “a consumer hack that, in the 2000s, before India’s cheap smartphone and data revolution, grew more popular than texting.”

“A missed call could mean ‘I miss you,’ ‘Call me back,’ or ‘I’m here.’”

“In 2008, one study estimated that more than half of Indian phone users were in the habit of calling people with the expectation that they wouldn’t pick up.”

Would it be possible to create a business out of this hack? “The idea of repurposing missed calls for commercial gain came to (Sanjay) Swamy, an entrepreneur and venture capitalist, and his colleague Valerie Wagoner in 2009, during a late-night flight from Delhi to Bangalore. Wagoner, an ambitious ex-eBay employee, had moved to Bangalore from California the previous year to work at mChek, a mobile payments startup headed by Swamy. On the flight, the two were discussing the difficulty of monitoring consumer behaviour in India, where over 95% of purchases were made offline and in cash, when they realized there was one method they had overlooked. Many Indian customers were already in the habit of texting ‘short codes’ to advertised numbers to receive offers and information from brands.”

It was only a matter of time before they created ZipDial. “With a couple of rings to the appropriate ZipDial hotline, customers received automated texts and callbacks that delivered live cricket scores for a big match, a deal on an affordable shampoo, rudimentary on-demand radio for Bollywood songs, or celebrity tweets—content supplied by brands that were struggling to reach offline consumers. In exchange, companies learned about their customers’ preferences and created viral offline marketing campaigns for their products.”

The story goes on to document in much detail how the company innovated relentlessly. “ZipDial, the industry’s poster child, always maintained that it was ‘not just a missed-calls company.’ Certainly, to call it that would be to shortchange its vision. The founders wished to position the company, as Wagoner told one newspaper in 2013, as ‘Google Analytics for the offline world.’… The company dealt in big data, and in an offline India, the missed call was the ideal tool to gather it.”

Then the smartphone happened, Reliance Jio got into the fray, the telecom narrative changed. ZipDial could have happened only in India.

Dig deeper

How to solve problems by cutting down, rather than adding up

[From Pixabay]

How to make roads safer? We are likely to say, add street signs or install traffic lights. But, as an article in Scientific American points out, urban planners made streets safer by getting rid of street signs and traffic lights in some European cities.

Even though we have come across leaders such as Steve Jobs who has found huge success by cutting down rather than adding up. He started his second innings in Apple by drastically cutting down the number of products in its portfolio. He launched the iPhone without a keyboard. But, that’s not common.

Scientific American describes a study that shows people tend to go the other way.

- In one [experiment], they asked 91 participants to make a pattern symmetrical by either adding or removing coloured boxes. Only 18 people (20%) used subtraction.

- In another, the team scanned through an archive of ideas for improvement submitted to an incoming university president and found that only 11% of 651 proposals involved eliminating an existing regulation, practice or programme.

- Similar results emerged across tasks that involved modifying structures, essays and itineraries—in each case, the vast majority of people chose to augment rather than remove.

This has important lessons for all of us. When trying to solve a problem, we can sometimes achieve better results by going against the natural inclination to add, rather than subtract.

Dig deeper

Still curious?

Indian innovation and entrepreneurship suffer because they rely too much on the Silicon Valley model without the Valley's infrastructure and ethos, writes Baba Prasad. Read: Indian Innovation: Too much Valley Kool-Aid without the Valley

Some of the most admired entrepreneurs started late in life. Dr G. Venkataswamy started Aravind Eye Hospitals after he retired; Steve Jobs was 52 when the iPhone was launched, writes Rishikesha T Krishnan. Read: Are you too old to be an entrepreneur?

Seeing things as they are, without letting our biases distort things, is key to taking the right actions, says Elizabeth Thornton in her book, 'The Objective Leader'. Read D Shivakumar’s The Gist: How to be an objective leader

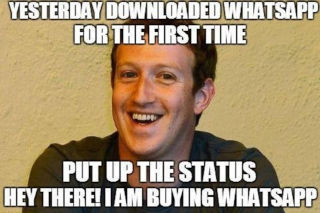

Mark Zuckerberg on WhatsApp

(Via WhatsApp)

Tell us what you think and find noteworthy.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)