[Image by fancycrave1 from Pixabay]

Good morning,

Tao of Charlie Munger is a compilation of insightful quotes from Warren Buffett’s partner at Berkshire Hathaway. Each of the 138 quotes in the book is accompanied by commentary from David Clark, co-author of the Buffettology series.

Quote #103 is about the idea of creative destruction applied to oneself. Munger’s quote goes like this:

“Any year that passes in which you don’t destroy one of your best loved ideas is a wasted year.”

Here’s Clark’s commentary: “What Charlie is saying is that in any year we haven’t tossed out one of our best-loved ideas, it probably means we aren’t reading and thinking enough to evolve a little bit further in our intellectual development. In the investment game, throwing out a well-loved investment idea can happen with some regularity. The world of business is a dynamic environment that can experience radical change over a very short period of time. In a mere seventy years the United States went from no electricity to the entire country being electrified. That completely destroyed candle making, gas lighting, and the kerosene lamp businesses, all great enterprises in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In 1930 there weren’t any televisions in people’s homes. By 1960 just about every American home had one, and the home radio business, the internet of the 1920s, pretty much died. In 2000 there wasn’t such a thing as Wikipedia. Today we can’t live without it, and Wikipedia killed the 244-year-old encyclopaedia business—which had been a really good business. In 1974 the digital camera didn’t exist. Today Kodak doesn’t exist—and for a hundred years previously Kodak had been an amazingly successful business! In the world of business and investing it is best to keep up with new developments and review our best-loved ideas every year, just to make sure that in thinking we are right, we don’t get it wrong.”

A few pages down the book there is a related idea about what might actually come in the way of getting rid of old ideas. It goes like this:

“Another thing I think should be avoided is extremely intense ideology because it cabbages up one’s mind.”

Clark explains, “Charlie believes that youth is easily influenced and often becomes obsessed with an ideology to the point that it is impossible to think of anything else or to see another side of an argument. Passion blinds young people to any kind of rational thought process.”

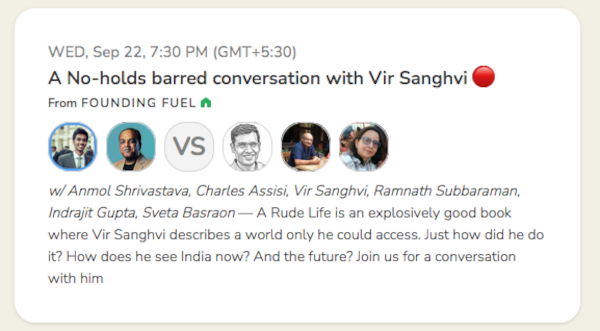

Later today: A conversation with Vir Sanghvi

Don’t miss the Founding Fuel conversation with Vir Sanghvi at 7.30 pm on Clubhouse

Click here to schedule, share and join the conversation.

In this issue:

- The unintended consequences of going organic

- Why work-life balance is a myth

- Cycle of life

Have a great day!

The unintended consequences of going organic

Earlier this year, Sri Lankan president Gotabaya Rajapaksa banned chemical fertilizers in the country to make the island go completely organic. But it might have set off a crisis. AFP reports that the “tea plantation owners are predicting crops could fail as soon as October, with cinnamon, pepper and staples such as rice also facing trouble.

“Sanath Gurunada, who manages organic and classic tea plantations in Ratnapura, southeast of Colombo, said that if the ban continues ‘the crop will start to crash by October and we will see exports seriously affected by November or December’.

“He said his plantation maintained an organic section for tourism, but it was not viable. Organic tea costs 10 times more to produce and the market is limited, Gurunada added.

“WA Wijewardena, a former central bank deputy governor and economic analyst, called the organic project ‘a dream with unimaginable social, political and economic costs’.

Dig deeper

Why work-life balance is a myth

In a recent book, Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals, Oliver Burkeman makes a provocative statement.

“Nobody in the history of humanity has ever achieved ‘work-life balance,’ whatever that might be, and you certainly won’t get there by copying the ‘six things successful people do before 7:00 a.m.’”

The four thousand weeks in the title of the book refers to the average lifespan of a person counted in weeks. In Mashable, Chris Taylor shares his key takeaways from the book.

He writes, “Burkeman doesn’t advise throwing out your productivity tools entirely. There’s nothing wrong with having a to-do list; as GTD [getting things done] guru David Allen says, capturing all your tasks enables you to only have a thought once (instead of having a brain that is constantly nagging you about what needs to get done next). Rather, you can use that list to be more mindful about how you’re going to procrastinate—because no matter what you do, you’re always procrastinating on something else.

“Four Thousand Weeks offers a number of strategies for better procrastination. You could try focusing on one big project at a time (or one big work project and one big personal project), while letting everything else lie fallow. Or you could ‘fail on a cyclical basis’—agree ahead of time that you’re going to do the bare minimum on your fitness routine during a month you’re canvassing for an election, say, then get back to the gym the following month. Instead of seeking the elusive work-life balance, you are ‘consciously imbalanced’.”

Burkeman suggests we have two to-do lists, Taylor points out. “One open and large, one closed and tiny. The open one is everything you could be doing; the closed one is a list of just 10 things you could achieve today.”

Dig deeper

Cycle of life

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)