[From Unsplash]

Good morning,

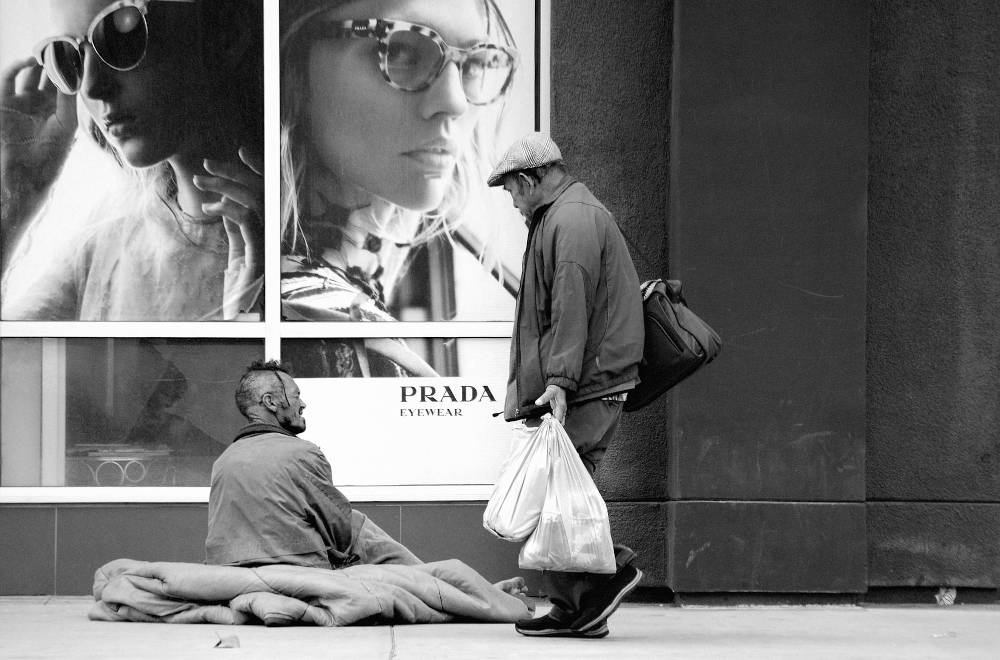

When Anand Giridhardas writes about the world’s elite in his deeply reported book Winner Takes All, he surfaces much that doesn’t get spoken about in the mainstream.

“Darren Walker, topped by a furry drum of a Russian hat, sat in the back of a black Lincoln limousine, inching nervously toward West 57th Street and what he called ‘the belly of the beast.’ His limo was heading to the New York office of KKR, the private equity firm immortalized in Barbarians at the Gate—a firm that had led the charge of the great rationalizing, one protocol-guided buyout at a time. Walker was the president of the Ford Foundation and thus in the social justice business. He spent his days giving money away.

“Walker’s assignment—to address a group of private equity executives at a luncheon—was complicated by a much-publicized letter he had written some months before. The letter broke with the pleasantness that tends to prevail in the philanthropy world. It had raised, in sharp and provocative language, the question of what to do about the crisis of inequality. This in itself was disturbing to many rich people, who preferred to talk about reducing poverty or extending opportunity, not about more thoroughgoing reforms that would perhaps require sacrifice. Walker’s letter had squarely blamed the very elites who give back through philanthropy for ignoring their complicity in causing the problems they later seek to solve.

“Before writing the letter, Walker had been universally popular with the plutocrats, which isn’t to say that everyone disliked what he had written. Robert Rubin, late of Goldman Sachs, Citigroup, and the Treasury Department, told Walker he loved the letter, finding it ‘fresh and different.’ He said he had ‘never read anything that did that.’ But many plutocrats objected to Walker’s shining the spotlight on inequality, instead of the issues they were more comfortable talking about, like poverty or opportunity. They disliked that he framed the issue in a way that blamed them rather than inviting them to participate in a solution. They disliked his focus on how money is made rather than how it is given away. ‘I just think you should stop ranting at inequality,’ a friend in private equity had snapped at him a few nights before the KKR event. ‘It’s a real turn-off.’ Walker had broken what in his circles were important taboos: Inspire the rich to do more good, but never, ever tell them to do less harm; inspire them to give back, but never, ever tell them to take less; inspire them to join the solution, but never, ever accuse them of being part of the problem.”

Think about that.

In this issue

- The other side of the TikTok screen

- Distraction sickness

- The Aadhaar Effect

The other side of the TikTok screen

Before India banned TikTok, through a series of stories—in collaboration with Quipper Research, led by its co-founder and CEO Piyul Mukherjee—we featured some of the biggest TikTok influencers, and followed it up with a fascinating discussion on its impact on business and society.

In Rest of World, Yi-Ling Liu, a China-based writer who covers the internet in that country, features Li Ziqi, a short video sensation with millions of followers on various social media platforms. The story is worth reading if only to understand the stunning contrast between the Indian and the Chinese internet (and therefore politics and society).

Liu writes: “Scenes from Li’s life—harvesting jujube dates, hatching ducklings, and simmering peach blossom wine—have mesmerized audiences around the world. She’s drawn a following of 55 million on Douyin, the local version of TikTok, and a YouTube subscriber base of 16 million (where she gained the Guinness World Records title for the most subscribers to a Chinese-language channel). She is beloved by fans from China to Portugal to Bangladesh, was named an ‘ambassador’ of Chinese culture by the Communist Youth League, and dubbed ‘Quarantine Queen’ by The New York Times. She is a balm for her followers’ high-pressure, screen-centric, time-constrained existences. Through her, they live vicariously in an online Eden, where pollution, industrial food chains, and coronaviruses cease to exist.

“But in reality, Li Ziqi is a complicated brand. Although she has created a virtual escape from the technological ills of modernity, her success is built around the very things that her lifestyle rejects.”

The ending makes a broader philosophical point. “People loved Li Ziqi because they believed that she, unlike her viewers, is free from the hyper-productive, capital-fueled, politically fraught world that they wake up to every morning. They believed that she was independent and beholden to no one. But behind the camera, Li Ziqi is just another player in the platform economy—on one hand, entangled in the profit-making machine of the short-video industry and, on the other, bound to the shifting rhetoric of Party politics—very much unfree, trapped within the same ‘real-world problems’ that have ensnared the rest of us.”

Dig deeper

- She drew millions of TikTok followers by selling a fantasy of rural China. Then politics intervened

- From the Founding Fuel series on TikTok

Distraction sickness

The narrative around how all things digital are a distraction is now a familiar one. That is why this essay in The New Yorker, that dates back to 2016, by the writer, editor, and blogger Andrew Sullivan continues to resonate. It talks about Sullivan’s addiction to all things tech and what it took to wean himself away.

“Think of how rarely you now use the phone to speak to someone. A text is far easier, quicker, less burdensome. A phone call could take longer; it could force you to encounter that person’s idiosyncrasies or digressions or unexpected emotional needs. Remember when you left voice-mail messages—or actually listened to one? Emojis now suffice. Or take the difference between trying to seduce someone at a bar and flipping through Tinder profiles to find a better match. One is deeply inefficient and requires spending (possibly wasting) considerable time; the other turns dozens and dozens of humans into clothes on an endlessly extending rack.

“No wonder we prefer the apps. An entire universe of intimate responses is flattened to a single, distant swipe. We hide our vulnerabilities, airbrushing our flaws and quirks; we project our fantasies onto the images before us. Rejection still stings—but less when a new virtual match beckons on the horizon. We have made sex even safer yet, having sapped it of serendipity and risk and often of physical beings altogether. The amount of time we spend cruising vastly outweighs the time we may ever get to spend with the objects of our desire...

“Yes, online and automated life is more efficient, it makes more economic sense, it ends monotony and ‘wasted’ time in the achievement of practical goals. But it denies us the deep satisfaction and pride of workmanship that comes with accomplishing daily tasks well, a denial perhaps felt most acutely by those for whom such tasks are also a livelihood—and an identity.

“Indeed, the modest mastery of our practical lives is what fulfilled us for tens of thousands of years—until technology and capitalism decided it was entirely dispensable. If we are to figure out why despair has spread so rapidly in so many left-behind communities, the atrophying of the practical vocations of the past—and the meaning they gave to people’s lives—seems as useful a place to explore as economic indices.”

Dig deeper

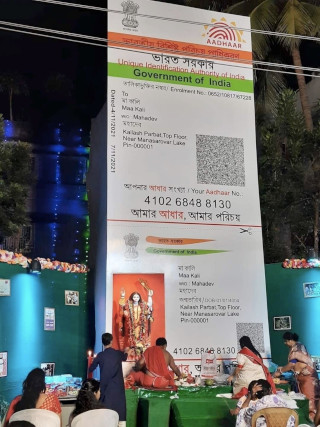

The Aadhaar Effect

(Maa Kali Aadhaar-style Pandal, West Bengal)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)