[From Pixabay]

Good morning,

In Making Numbers Count: The Art and Science of Communicating Numbers, Chip Heath and Karla Starr share some tricks employed by brilliant minds. One of them is Grace Hopper, a US Navy Rear Admiral, computer science pioneer, and before that a teacher of mathematics at Yale.

Heath and Starr write, “Hopper pressed her engineers to streamline their code. (In wartime, a fraction of a second can separate life from death.) During lectures, she would hold up a bundle of wire cut to the length that electricity traveled in a microsecond, or 1 one-millionth of a second. It was 984 feet long. She said, ‘I sometimes think we ought to hang one [of these bundles] over every programmer’s desk, or around their neck, so they know what they’re throwing away when they throw away microseconds.’

“‘Wasting a microsecond’ inspires as little concern as ‘wasting half a penny’ until we see how far a signal could have traveled in that time. By turning the microsecond into a concrete object—concrete enough to drape around the neck of a programmer, and make a life-and-death difference in a war—Hopper made an immortal point.”

Later on they explain how Hopper could have done even better, and that underlines how we can think creatively about communicating numbers in this Age of Data Analytics.

They write: “Hopper’s 984 feet of wire is showing the number. But if she wanted to make it into an even more memorable demonstration, she could have taken it a step further and really made her programmers experience the number. For example, if she’d tied teams of two programmers together and made them race this distance in a three-legged race. Even the fittest navy midshipman (Hopper was a rear admiral as well as a programmer) would have trouble getting through 984 feet of a three-legged race in good shape. Afterward she could tell them, ‘The distance you raced is what an electrical signal travels in a microsecond. Don’t waste those!’”

What are your favourite tricks in communicating numbers? Let us know.

India at the crossroads?

When we ask India optimists why the stock markets are booming, a narrative we hear is that they expect a boom in domestic consumption around the third quarter of 2022. Then there is another narrative that isn’t as sanguine about India given how things look now. Consider Bloomberg columnist Andy Mukherjee’s view, for instance.

“The chest-thumping nationalism of the last eight years has led to a repudiation of the gradual opening up of the previous three decades. More than 3,000 tariff increases have affected 70% of imports. India entered 11 trade agreements in the 10 years under previous Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. On Modi’s watch, it hasn’t signed even one. Although the country is starting negotiations with post-Brexit Britain and Australia, and claims to be close to a pact with the United Arab Emirates, bilateral deals won’t compensate for the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a free-trade accord linking Asia’s exporting powerhouses. New Delhi turned its back on RCEP in 2019.

“This protectionist drift springs from the belief that an economy of 1.4 billion consumers is large enough to be powered by internal demand. But, as Subramanian’s previous work with Pennsylvania State University economist Shoumitro Chatterjee has shown, even before Covid-19, no more than 1%-to-2% of the population could be described as middle class, compared with 25% in China. Such a tiny font of purchasing power could at best drive $500 billion in spending. World trade, meanwhile, is a $28 trillion opportunity, with much smaller countries like Vietnam making a determined play to win market share.”

How do you think about it? Let us know.

Dig deeper

A 21st century pandemic

In Wired, Howard Markel, an American physician and medical historian writes about why the ongoing pandemic is like none other the world has seen before.

He writes, “Although I hate to put myself out of business as a historian of quarantines, I must insist that in managing our contagious future, in ensuring that future pandemics end sooner than our current one, we will no longer look to our distant past for pandemic control because those eras no longer reflect our hyper-connected world, where news, information, disinformation, and scientific data travel at the speed of electrons. That is why this is the pandemic I will be studying and teaching in the years to come. This is the first pandemic where we have had so many tools for surveillance, identification, and means to determine the virus’s ever-changing genome and viral dynamics. The public health problems that have emerged during this pandemic are 21st-century problems and demand 21st-century approaches. The other epidemics still have much to teach us, but studying Covid is our best hope for succeeding when the next pandemic strikes.”

Dig deeper

A fast-paced world

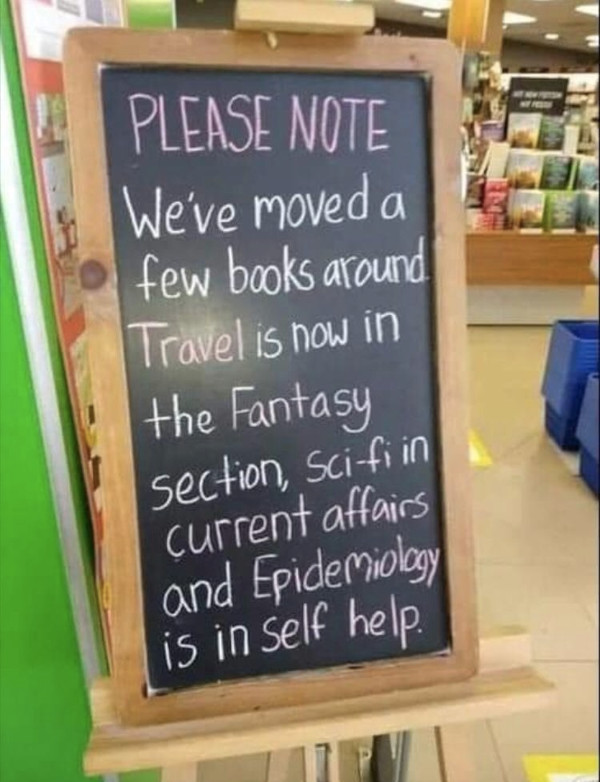

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel

(Note: Founding Fuel may earn commissions for purchases made through the Amazon affiliate links in this article.)