[From Unsplash]

Good morning,

We’re taking our time to read and think through How to Live: 27 Conflicting Answers and One Weird Conclusion by Derek Sivers. It hit the shelves recently and contains his reflections on life. It has our attention because each chapter contradicts the other. And all of it is true. To begin with, consider some of the arguments Sivers makes to live a life devoted to commitment.

“New habits are what you’re trying.

Old habits are who you are. Commit to one career path.

Build your expertise and reputation over time.”

“This even goes for technical choices, whether hardware or software.

Pick one.

Commit to it.

Learn it deeply.

This is much more rewarding than always switching and searching for the best.”

“Falling in love is easy.

Staying in love is harder.

Enthusiasm is common.

Endurance is rare.”

“Commitment gives you peace of mind.

When you commit to one thing, and let go of the rest, you feel free.

Once you decide something, never change your mind.

It’s so much easier to decide just once.”

Having done that, he dives into why there is wisdom in the pursuit of pleasuring the senses.

“Never have the same thought twice.

Keep nothing on your mind.

Just take in what’s around you now.

Have no expectation of how something should be, or you won’t see how it really is. How amazing that everything you’re doing is both the first and last time.

The thrill of the first.

The sentimentality of the last.”

Exasperated? Intrigued? We’re still thinking it over. Let us know what you think. And have a good day!

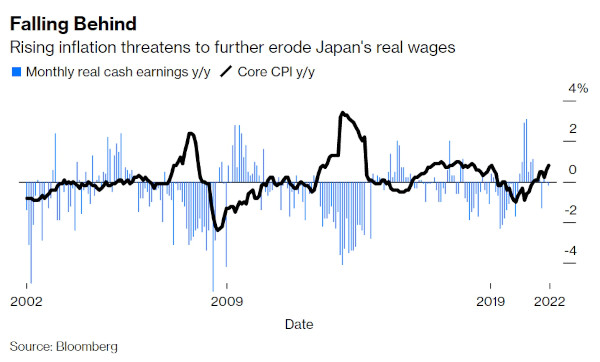

Japan has a problem

One of the reasons we follow Noah Smith’s blog posts is because it often surprises us. He used to be a columnist for Bloomberg and taught finance in earlier avatars and is now on a visit to Japan. Smith’s posts from the country offer counterintuitive insights. We always thought of Japan as a rich country. However, he notices what most of us are unaware of. That “underneath the gloss of that fantasy-land exterior, Japan as a whole is not exactly thriving. For decades, the country’s real wages have drifted downward”.

“What does this mean in practice? First of all, it means that many Japanese people are suffering in quiet, hidden poverty… Women tend to be shunted into dead-end, low-paid part-time work, and many slip through the cracks in the pension system. It also falls disproportionately on the young, because of Japanese companies’ habit of basing wages mostly or entirely on seniority. These folks are out there scrimping and saving and working long hours at dreary, monotonous, soul-crushing jobs, sleeping in tiny bare rooms, desperately pinching pennies, able to afford fewer and fewer luxuries every year.

“Even for those who manage to land a middle-class job, the lifestyle is often soul-crushing. Japan’s famous culture of overwork rewards employees who put in long hours at the office instead of those who accomplish tasks quickly and efficiently. This is mostly a result of the country’s notoriously low white-collar productivity rates—workers are working overtime to make up for broken corporate cultures. But it’s also likely that there’s a feedback loop involved; excessively long hours have been shown to make workers tired and ineffective.”

Dig deeper

Systemic stupidity

Why is it that people believe in ideologies and lose all rationale? This is a question that lurks in the corner of our minds when we think about the nature of current public discourse. Pointers to how to think about it lie in an interesting essay on the many kinds of stupidity by Ian Leslie, the British author who writes on psychology, technology, culture and business.

“Stupidity can be systemic. The Santa Fe Institute complexity theorist David Krakauer observes that the Romans, as intelligent as they were in many ways, made no advances in mathematics. He puts this down to a numeral system that made it virtually impossible to do complex sums. Arabic numbers, imported to Europe in the Middle Ages (not as dumb as their reputation), are easier to manipulate. The new system made our civilisation collectively smarter, or at least less dumb. The tool or platform we’re using can keep us stupid, even when we’re smart. In fact, Krakauer’s view is that stupidity isn’t the absence of intelligence or knowledge; it’s the persistent application of faulty algorithms (itself an Arabic concept, of course). Let’s say someone hands you a Rubik’s Cube.

“Consider three possibilities. You might know an algorithm or set of algorithms which enables you to solve it quickly, and look very smart (actually Krakauer would say that is a kind of smartness). Or you might have learnt the wrong algorithms—algorithms which ensure that no matter how many times you try, you’ll never solve the puzzle. Or you might be completely ignorant and just go at it randomly. Krakauer’s point is that the ignorant cuber at least stands a chance of solving it accidentally (theoretically speaking—don’t try this at home) whereas the faulty-algorithm cuber never will. Ignorance is insufficient data to solve a problem efficiently; stupidity is using a rule where adding more data doesn’t improve your chances of getting it right—in fact, it makes it more likely you’ll get it wrong…

“You find a lot of stupidity among people who are highly partisan on behalf of a political party or ideology. Those people tend to be cognitively inflexible, regardless of which side they’re on.”

Dig deeper

A tragic story

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel