[From Pixabay]

Good morning,

Most public narratives have it that the MVA government in Maharashtra was firmly in the saddle. Overnight, that narrative changed and a question mark now hangs over the future of the government. Whether it may get dislodged or manage to cling to power by the time this newsletter hits your inbox, we’ll get to know as developments unfold. But that’s politics for you. So, how is it that leaders who appear to be in charge lose the plot? To look for answers, we turned to the pages of Shivam Shankar Singh’s book How to Win an Indian Election.

“I have heard spokespersons of parties in TV studios before debates talking about what their leadership is doing wrong and what needs to be fixed within their parties, but these opinions almost never reach the ears of the party supremo. Critical feedback can easily be misinterpreted as blame, and that would risk the messenger’s own political career. It is a risk that no politician is willing to take. A lack of feedback often leaves party leaders misinformed, and several of them end up overestimating their chances of winning elections based on the overly positive feedback provided by people close to them. It has harmed leaders during several elections, yet few ever find a way to address their party workers’ fears so that they can get accurate assessments of the ground realities.

“The supremacy of a party leader’s directives is illustrated by a story told to me by Trinamool Congress (TMC) MP Dinesh Trivedi. Trivedi is a senior leader who has been active in politics since the 1980s. He became a Rajya Sabha MP for the first time in 1990 on a Janata Dal ticket and has been in the Lok Sabha since 2009 representing TMC. During my year as a LAMP fellow, he invited a group of us for tea to his MP quarters in Lutyens’ Delhi. The conversation veered towards the time when he had to resign from the post of Union railway minister in 2012. The story is that he had raised rail tariffs after giving hints to everyone that he would be doing so. No one objected to that when they initially heard about the hike, but once the railway budget was publicly released, there was tremendous criticism from the Opposition. The hike was condemned as being against the interests of the common man, who would now have to pay more for train tickets. Due to the widespread criticism, the head of TMC, Mamata Banerjee, asked Trivedi to step down as railway minister. He resigned immediately. I asked him why he didn’t mount a defence, a question that was especially relevant then because the Modi government had substantially increased the train fares and there was no opposition to the move. The answer proved to be a valuable lesson in politics. He told us that he’d become railway minister only because ‘Mamata Di’ had given him the portfolio. It really wasn’t his post. Since the leader of his party had entrusted it to him, when she became convinced that the right move was for him to resign, there was no point in mounting any kind of a defence.”

Have a good day!

Five habits that matter

Since the time Rishad Premji took over as executive chairman of Wipro, there have been murmurs that something about the company is changing. “The culture” is what most narratives have it. But just how do you change culture? Anuj Kadyan of McKinsey & Co sat down with Premji to understand this and we read the conversation with much interest.

McKinsey: The architecture of Wipro’s cultural-transformation program places a big emphasis on cultivating five core habits. What are these habits and why were they chosen?

Rishad Premji: The discovery of the five habits happened by accident. After my one-on-one conversations, the top 15 company leaders came together to set up four task forces—on collaboration, non-negotiable behaviours, stewardship, and metrics. These teams spent an enormous amount of time among themselves, meeting alumni, people across the organisation, and, in some cases, talking to customers to figure out what we needed to do to improve our performance.

When these 15 leaders were debriefed later, we learned that the task forces were hearing a lot of the same things in different words, so we decided to demystify and bring it all together.

We were also very clear that we wanted to focus on behaviours, things people could control as individuals. There was nothing “aha” about these habits. They were powerful in their simplicity. We also tried to make sure that they were universally applicable and would not get lost in language, local culture, and nuances. My 14-year-old daughter would understand them and be able to interpret them in the same way as somebody sitting in Hyderabad, Manila, Cincinnati, or London.

The first habit is being respectful, which is about being inclusive, communicating transparently and authentically, even when it comes to feedback. The second is about being responsive, both to our clients and inside the organisation, and making decisions at speed and taking risks. The third is about always communicating—with stakeholders inside the organisation and with customers, as well as sharing bad news quicker and faster. The fourth is about demonstrating stewardship. It is about having a strong mindset, having a ”can do” attitude as opposed to a cynical attitude, and sharing your best people and helping other parts of the organisation, even if there is no benefit to yourself. The last one is about building trust across the aisles. In an organisation where 100,000 new people have joined in the past two and a half years, the element of trusting people before you know them is incredibly important to getting things done in a collaborative manner.

Dig deeper

Indian protest rap

In BBC Culture, Charukesi Ramadurai explores the fascinating world of protest rappers in India, and how singing in local languages is shaping its own unique style.

Ramadurai writes: “In the last few years, young people in India have… begun to use rap as a means of dissent, even as human rights organisations have alleged that the Indian government has increasingly come down hard on critics of its regime. What they are speaking about is somewhat similar to African-American rappers, ranging from discrimination and marginalisation to governmental apathy. ‘I use rap to convey the anger inside me, the anger I have had for many years. Rap allows me to speak about my own life experiences,’ Arivu, who speaks for the Dalit community that he belongs to, tells BBC Culture…

“Protest rap has also been so popular in India because most of the artists have chosen to rap in their own regional languages—whether Tamil or Punjabi or Assamese. This not only allows them to express themselves fluently but also connect better with their peers in the hinterlands. (One of the notable exceptions is MC Kash, who used English to make audiences outside India aware of the situation in Kashmir). It is also interesting that these young rappers have drawn from the traditional music forms of their own region or community. Krishna says that there is no single uniform rap style in India. ‘For instance, Tamil rap has its own characteristics, it derives from local koothu and gaana tradition. These rappers are not just copying African-American rap, but are making it their own,’ he says.”

Dig deeper

Thursday thoughts

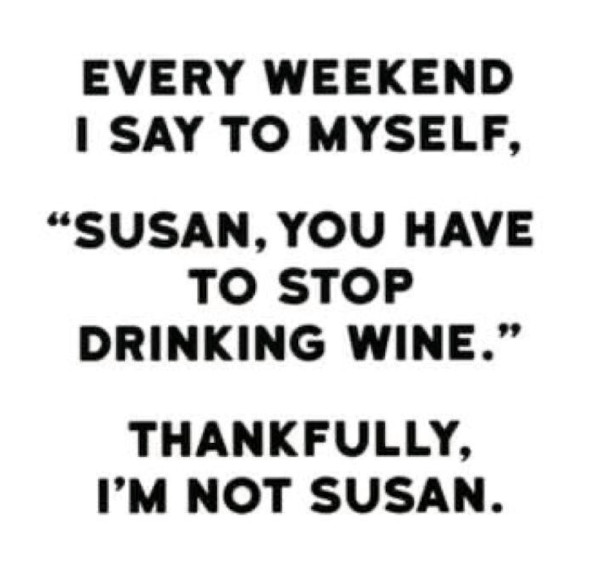

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel