[From Unsplash]

Good morning,

In How to Make the World Add Up: Ten Rules for Thinking Differently About Numbers, Tim Harford shares a fascinating study by researchers led by Yale University’s Dan Kahan. It throws some light on why in the polarised world more information doesn't translate to creating a middle ground where people can come together to have open discussions.

In the study the researchers showed “students some footage of a protest outside an unidentified building. Some of the students were told that it was a pro-life demonstration outside an abortion clinic. Others were informed that it was a gay rights demonstration outside an army recruitment office. The students were asked some factual questions. Was it a peaceful protest? Did the protesters try to intimidate people passing by? Did they scream or shout? Did they block the entrance to the building?

“The answers people gave depended on the political identities they embraced. Conservative students who believed they were looking at a demonstration against abortion saw no problems with the protest: no abuse, no violence, no obstruction. Students on the left who thought they were looking at a gay rights protest reached the same conclusion: the protesters had conducted themselves with dignity and restraint.

“But right-wing students who thought they were looking at a gay rights demonstration reached a very different conclusion, as did left-wing students who believed they were watching an anti-abortion protest. Both these groups concluded that the protesters had been aggressive, intimidating, and obstructive.”

Harford goes on to write: “the way our political and cultural identity—our desire to belong to a community of like-minded, right-thinking people—can, on certain hot-button issues, lead us to reach the conclusions we wish to reach. Depressingly, not only do we reach politically comfortable conclusions when parsing complex statistical claims on issues such as climate change, we reach politically comfortable conclusions regardless of the evidence of our own eyes.”

Have you thought about this problem? Do you have any solutions? Harford’s book has some, but we would love to hear from you.

Have a great day.

The Art of Humility

Ranjan Sen, who subscribes to this newsletter, pointed us to an absolutely delightful essay by David Brooks on the rules of humility in the age of social media. It is at once caustic and insightful.

“I have spent years studying the fine art of humility display, and I am humbled by her masterful show of it. If you’ve spent any time on social media, and especially if you’re around the high-status world of the achievatrons, you are probably familiar with the basic rules of the form. The first rule is that you must never tweet about any event that could actually lead to humility. Never tweet: ‘I’m humbled that I went to a party, and nobody noticed me.’ Never tweet: ‘I’m humbled that I got fired for incompetence.’

“The second rule is that you must always use the word humbled when the word proud would actually be more accurate. For example: ‘Humbled to be make the 100 Under 100 list in Arbitrary Lists Magazine,’ ‘Truly Humbled to be keynote speaker at TedXEastHampton,’ ‘Humbled that Cameron Diaz is giving me a ride to Bradley Cooper’s surprise birthday party.’ The key to humility display is to use self-effacement as a tool to maximise your self-promotion.

“The third rule is that you must never use a pronoun.

“The art of humility display goes back centuries… But the advent of social media has heralded a golden age of humility display.”

We are humbled Ranjan subscribes to this newsletter and chose to share this with us. Truly!

Dig deeper

Short-term vs long-term status

When scrolling through the archives of Sam Altman’s personal blog, CEO at OpenAI and former president of Y-Combinator, an interesting post of his from a few years ago had our attention. A startup founder had asked Altman how to stop caring what other people think about him. Altman admits he did not have an answer right away. But on reflection, it occurred to him that perhaps that’s a wrong question to ask. Because most people care how others think about them.

His observations have it that “The most impressive people I know care a lot about what people think, even people whose opinions they really shouldn’t value (a surprising number of them do something like keeping a folder of screenshots of tweets from haters). But what makes them unusual is that they generally care about other people’s opinions on a very long time horizon—as long as the history books get it right, they take some pride in letting the newspapers get it wrong.

“You should trade being short-term low-status for being long-term high-status, which most people seem unwilling to do. A common way this happens is by eventually being right about an important but deeply non-consensus bet. But there are lots of other ways—the key observation is that as long as you are right, being misunderstood by most people is a strength, not a weakness. You and a small group of rebels get the space to solve an important problem that might otherwise not get solved.”

Dig deeper

The strength of being misunderstood

Staying motivated

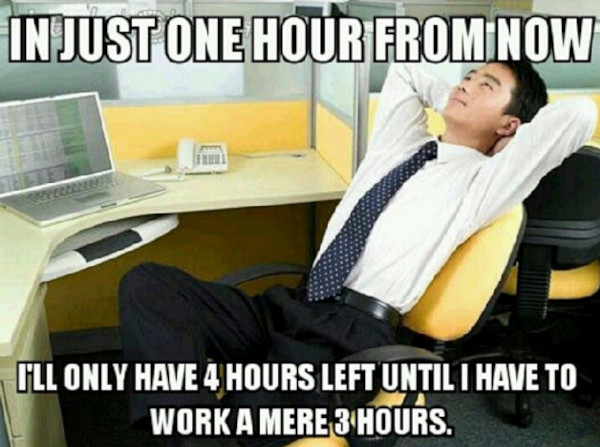

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel