[From Unsplash]

Good morning,

In The Long Game: How to Be a Long-Term Thinker in a Short-Term World, Dorie Clark, an executive education professor at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, talks about the importance of treating some of the early work that we do as experiments, and look at failures as opportunities to learn.

Drawing on the work of Steve Blank and Eric Ries she argues that there is much to be learnt from Silicon Valley’s philosophy of ‘test before you invest’.

She writes, “All too often, smart professionals hesitate to put their ‘thing’—whether it’s an article, a new website, a talk, an idea—out into the world. ‘It’s not quite ready yet,’ they’ll say, or ‘I’m still making a few tweaks,’ or ‘It needs a little more time.’ That’s fine up to a point; you don’t want to release something into the world that’s awful, or so rough that it’s unintelligible. But after a while, this kind of thinking becomes an excuse that can hold us back.

“The lesson we can learn from Silicon Valley and the lean startup methodology is that we should, in the early days, treat everything as an experiment. Failure is upsetting to so many of us because it implies finality: you tried to accomplish something, and it didn’t happen. But an experiment, which you recognise from the beginning has an uncertain outcome, can hardly be called a failure. You know it’ll take multiple iterations to get the result you want, and you set your expectations accordingly. As Thomas Edison is supposed to have said, it’s finding 999 ways not to invent the light bulb. You haven’t failed—you’ve gotten data that helps you refine your approach so you can succeed in the future.”

Have a great week ahead!

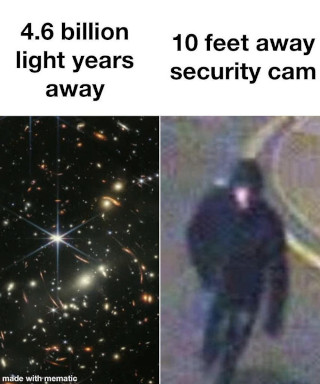

James Webb’s impact

Over the last few days our social media timelines and WhatsApp groups were flooded with images from James Webb Space Telescope. They were fascinating, like the one of Carina Nebula here.

However, the consequences of the telescope will be far reaching than the spectacular pictures. Arjun Chaudhuri explains why. (Arjun Chaudhuri is a student of Economics and Public Policy at the University of Toronto. He works as a researcher at the Munk School, conducting his own research in public administration in South Asia. He is currently interning at Founding Fuel.)

He writes: “Webb can see objects 450 million lightyears farther than Hubble. It can see the universe as it was 13.75 billion years ago, before the first stars sputtered into existence. By observing this time, astronomers hope to understand how matter, dark matter and dark energy came to be. We have some ideas but we don’t know if they’re right.

“Learning about this time in the universe’s past may induce a ‘paradigm shift’ in science. The last time we experienced such an event was the movement from Newtonian to Einsteinian physics. Consequently, we have completely revolutionised our energy systems, through the development of nuclear power, our modes of communication through satellite-powered television and radio, and how we share and store information with the advent of the internet. If you choose to buy into the ‘nuclear deterrence theory’, we may even have prevented the outbreak of a third World War by building nuclear weapons. The ‘dark energy’ paradigm shift would have similar consequences.”

Dig deeper

What can’t be taught

Once upon a time, Saina Nehwal was the toast of the country. She was #1 on the global badminton circuit, represented India thrice at the Olympics, and even got a Bronze for her effort in 2019. But as things are, in a profile of where Nehwal finds herself now, Shivani Naik writes in The Indian Express that “There’s no dearth of teachers wanting to teach Saina Nehwal a lesson.

“A federation that she doesn’t vivaciously correspond with, senior citizens of the sport and of administration she doesn’t kowtow to, fellow players she’s always remained aloof as that’s her core nature, fans who crinkle their noses at her selfie-posting indulgence and detractors who are annoyed by her confounding political immersions. Nehwal has learnt to park herself at the T and scatter opponents’ wits from across the court with her canny flicked angles when she plays badminton. But it has dawned upon her in the last few months just how much of a lonesome corner she has driven herself into, by not sticking to the shrinking-flower role of a fading former star, who’s supposed to be humbled by the ageing of her body and diminishing of her on-court prowess.”

Aged 32, everyone thinks she must go. But Nehwal isn’t willing to yet. She may have slowed down. But she still has a fire that few people possess. “The door slammed on her face—you can still hear her persistent knocks. Knowing Saina Nehwal, she would want to kick it open, rather than wait for anyone to politely invite her in. Even the best teachers know that particular quality can’t be taught.”

Dig deeper

The paradox

(Via WhatsApp)

Found anything interesting and noteworthy? Send it to us and we will share it through this newsletter.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel