After decades, I started reading comics thanks to my nephew Om’s love for superhero movies, games and comics. One book led to another and I am discovering a whole new world.

The first book that made me sit up was Art Spiegelman’s Maus. I picked it up because it won a Pulitzer Prize back in 1992. I read it in one sitting because the story — of Spiegelman’s father, a Holocaust survivor — was so compelling. And then I read it again, slowly and carefully.

Eventually, I found Joe Sacco’s Palestine. It’s a journalistic work. Sacco tells the story of his visit to the conflict zone. But it was different from what I read in newspapers or watched on television.

I could relate to what philosopher Edward Said wrote in the introduction of the book: “As we also live in a media-saturated world in which a huge preponderance of the world's news images are controlled and diffused by a handful of men sitting in places like London and New York, a stream of comic book images and words, assertively etched, at times grotesquely emphatic and distended to match the extreme situations they depict, provide a remarkable antidote.”

It was an antidote I very much needed. I am still early in this journey, but I can already see it has helped me in two specific ways.

It helped me understand the power of visual language and helped me as a journalist and storyteller. For example, in Maus, Art Spigelman depicts the Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. The imagery is so strong that even when he is narrating a happy episode, you are aware of the dark clouds above, and the impending doom. Recognizing its power helps me whether I was working on a deck, or an infographic series like this one.

It also helped me in a more important way, at a time when we want to rush through things, often with the help of technology. How easy is it to ask Claude to summarize a long story, and therefore, how easily do we miss some of the nuances that come only from deeper engagement? There is something about graphic novels that makes us pause and reflect. It’s a skill one can take to other aspects of life.

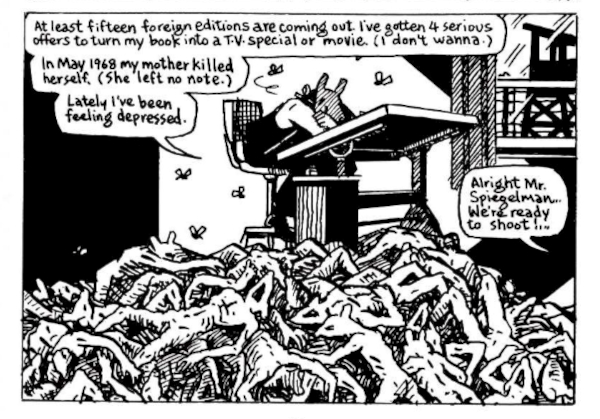

Let me start with a single image from the second volume of Maus. It shows Spiegelman leaning over his work table, informing the readers about the response to the first volume. A speech bubble also reveals he is getting ready for a television interview. But right under his feet, there is a heap of Holocaust victims.

I want to start with this image because it captures several key lessons I want to share.

The New York Times Book Review once asked Spiegelman about this image, and he replied: “That was a concrete realization of what I was feeling while I was creating some of the material in Maus II.

In my line of work, one is always hunting for that essentialization. Comics do that especially well. They permit you to boil down an image and a thought to its essence, with the two circuits mixing the words and images. In that frame, I drew myself sitting over the dead bodies, while people are clambering up the mound in order to interview me about how swell Maus I was. It was how I felt.”

There are two things here.

Simplify simplify simplify

One is the obsession with simplifying.

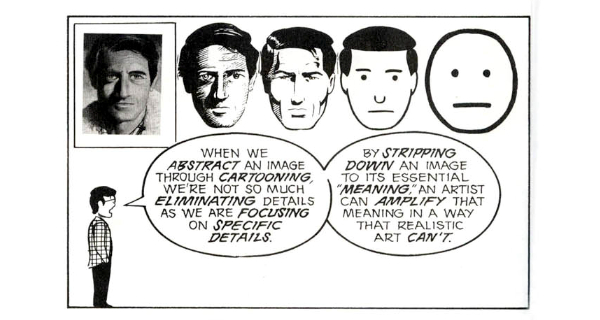

Scott McCloud, American cartoonist and creator of Zot!, a popular comic book in the 1980s, explains this beautifully in his book Understanding Comics.

It’s important to note here that the purpose of stripping down is to find the essential meaning. As Apple’s Jonathan Ive explained, “Simplicity is not the absence of clutter, that's a consequence of simplicity. Simplicity is somehow essentially describing the purpose and place of an object and product. The absence of clutter is just a clutter-free product. That's not simple.”

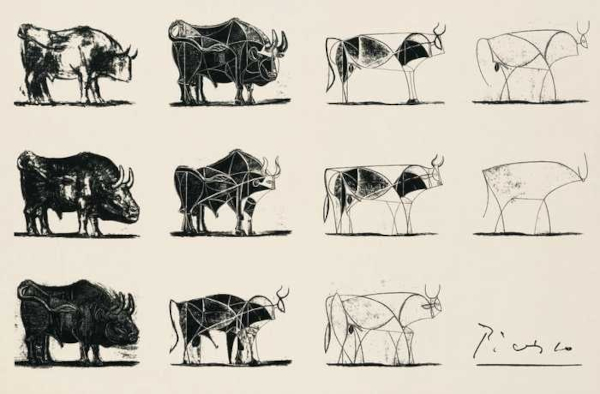

It’s something that Picasso wanted to convey when he created this.

If we go back and look at Spiegelman’s image, it’s not clutter-free. Yet, it’s simple, in the sense that it strips down his complex feelings of that time about his book, its reception, and his struggle to deal with its core subject — the Holocaust.

That brings us to the second point.

Capture the complex

Comic artists are always seeking to capture complex experiences, and the format allows them to do that in a way other formats can’t.

In the image, he captures that using two metaphors — the flies around his head, and the body heap under him.

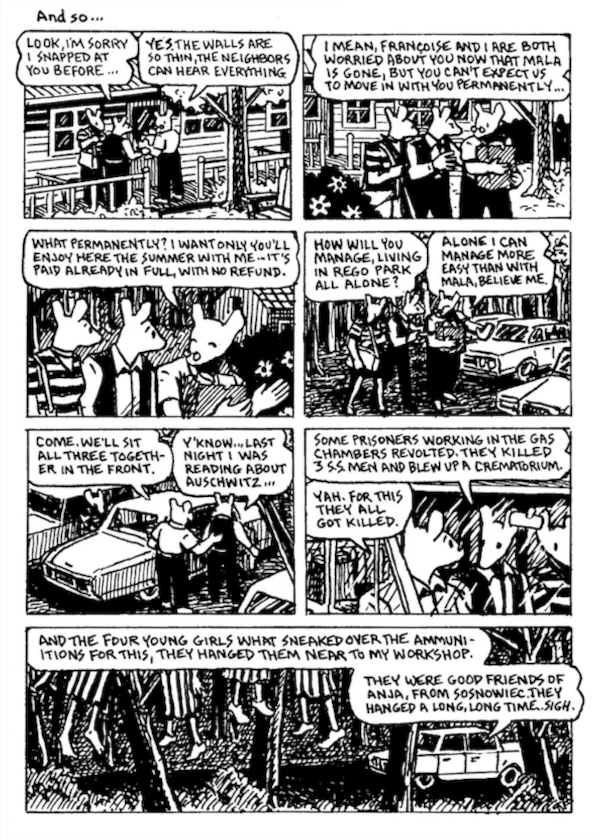

We come across this technique often in comics. Here’s another haunting page from his book.

The scene itself takes place in the 1970s. They are driving through the woods. His father is telling Art about his experience at Auschwitz, about the hanging of four young girls at the camp. The last panel crunches time and geography and puts the Auschwitz of the 40s and the America of the 70s in one single frame.

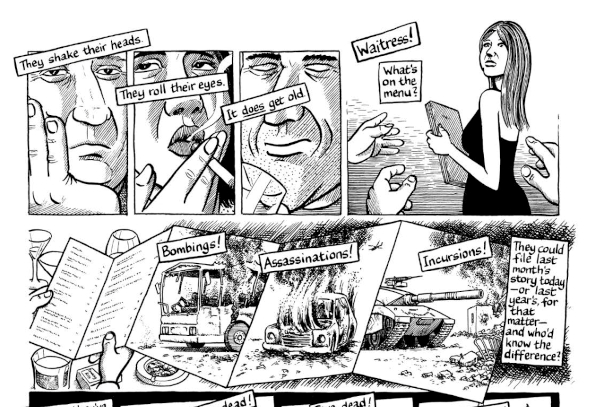

Here is another frame from Joe Sacco’s Footnotes from Gaza. He is with a bunch of journalists at a restaurant in West Jerusalem. They chat about what’s going on. He asks the waitress for the menu. And what does it show?

Or check out this from Japanese artist Keiji Nakazawa’s I saw It, his experience of Hiroshima.

In her brilliant book, Why Comics? From Underground to Everywhere, Hillary Chute, a professor at Northwestern University, and a comics and graphic novels columnist for the The New York Times Book Review, explains what is going on inside the panels.

“The page that shows the bomb detonating illustrates how comics narrative can capture what we might think of as both exterior and interior trauma. As we can see on this page, I Saw It races back and forth between perspectives: if one panel pictures the narrator’s body on the page, the very next pictures his own optical perspective. To depict the tremendous, white-hot flash of the bomb’s detonation, Nakazawa draws it overpowering a narrow, elongated panel, which is stamped in the upper-right corner with the explosion’s exact time: 8:15 a.m. Simultaneously, the image records one young boy’s act of eyewitnessing and acts as a historical marker of a momentous event. On the upper-right corner of the page, in the same tier as the flash, is an even more commanding panel that captures the expressionistic sights Keiji saw just before falling unconscious: a tree severs in two, a torrent of roof tiles rushes by. It is the kind of image that can’t be photographed, and that is seared into one’s memory.”

(Chute also collaborated with Art Spiegelman to bring out MetaMaus, a companion volume to Maus).

Crunch space and time

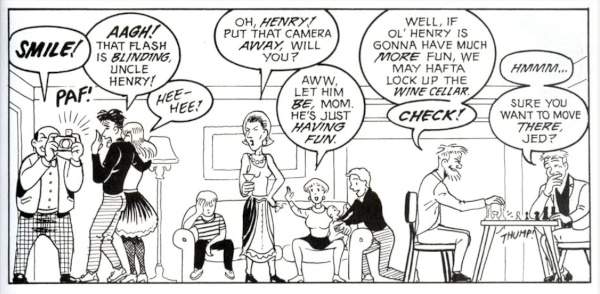

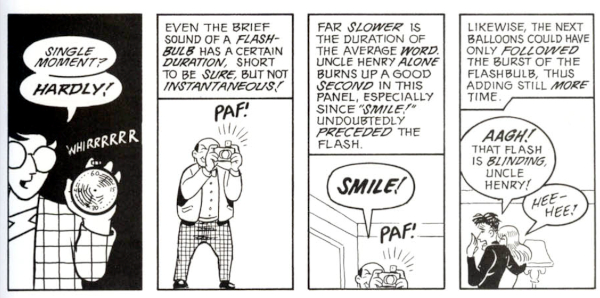

While the car trip that Spiegelman took with his father dramatically crunches space and time, it is very fundamental to the art of comics. But often we read them without giving any thought.

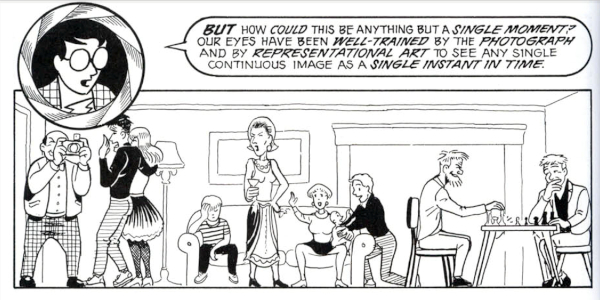

Scott McCloud visualises it this way.

Scott McCloud’s comparison of comic panels with photography brings me to another point, another comparison, which is this: Even movies give us a combination of images and words, so what’s the big deal about comics?

Engage

The comic format allows us to pause, spend as long as we want on a page, and go back to a few panels, just to make sense of the story better. Technically, you can do that in a movie too, if you are watching one at home on Netflix or on your good old CD player. But, doing that can take away your experience. In comics, doing that will enhance your experience.

Going back to the image from Maus, you just don’t turn the page. You close your eyes. The heap of bodies reminded me of lines from Two Lives by Vikram Seth. I pulled out the book and read them: “Lola’s naked body, grotesquely contorted, possibly broken boned, her face blue and unrecognizable and bleeding from mouth and nose, her legs streaked with shit and blood, would, after a hosing down, have been dragged out of the room, possibly with a noose and grappling hook….”

Push your boundaries

Comics emerged from the underground, as the subtitle of Chute’s book highlights. As a result, they explored themes that were not palatable to the mainstream. But the mainstream also shies away from discussing important issues. Discussing Hiroshima was a taboo in Japan for a long time, till Nakazawa published his comic books. You might just pick up something important early on, much before the mainstream does, in your explorations. You might then be able to engage with such topics before they get hijacked by polarised debates. For example, Amruta Patel’s graphic novel Kari explored the themes of gender and homosexuality back in 2008, and allowed readers to engage with it, without getting distracted by controversies. That’s because, Patel once explained, the publishers marketed it not as an LGBT novel, but just as a graphic novel.

Here are five books to start your journey.

Maus

Who’s the author: Art Spiegelman, cartoonist and comics editor, who experimented with underground comics, before taking up Maus

What’s the book about: It tells the story of Spiegelman's father, Vladek, a Holocaust survivor, while also exploring the complex relationship between father and son. Through a dual narrative and the creative use of animal metaphors, the graphic novel delves into the horrors of the Holocaust, the struggle for survival, and the intergenerational impact of trauma. It also showed that this form can tackle serious subjects with depth and nuance. It earned Spiegelman a Pulitzer, the first time a graphic novel got the honour. But Spiegelman himself had a dislike for the term graphic novel.

Persepolis

Who’s the author: Marjane Satrapi, French-Iranian graphic novelist, who has also directed five movies, including the film version of Persepolis.

What’s the book about: It's a series of autobiographical graphic novels portraying Satrapi's childhood in Iran during the Islamic Revolution. It makes you reflect on the impact historical events have on ordinary citizens as they navigate political turmoil, war, and repression — and the power dynamics between rulers and their people. The work is in the tradition of Spiegelman. But, Satrapi's style is simpler and more minimalistic and it impacts you differently but as powerfully as Maus.

All Quiet in Vikaspuri

Who’s the author: Sarnath Banerjee’s first graphic novel, Corridor, came out in 2004. His most recent book, The Moral Contagion, released this year is about pandemics.

What’s the book about: Banerjee tells the story of a plumber who goes on a journey to the centre of the earth in search of the river Saraswati, even as war rages between a fictional Delhi, which is starved of water. You can see why it resonated with me, as I type out this from Bangalore, which is facing a water crisis. But, the bigger reason is the way Banerjee uses this narrative to mix satire, myth and social commentary.

Banerjee recently teamed up with MIT economist Abhijit Banerjee to bring out a documentary that touches on this theme. You can check them out here. https://arts.mit.edu/people/sarnath-banerjee/

(If you would like to pair it with another work of fiction, I would highly recommend Kari, by Amrutha Patil. If you want to try out a completely different genre, check out The Sandman by Neil Gaiman.)

Palestine

Who’s the author: Joe Sacco: Joe Sacco pioneered comic journalism

What’s the book about: First published 30 years ago, Palestine is one of the finest examples of comic journalism. It is based on his trip to the West Bank and Gaza Strip in the early 1990s. Through a combination of in-depth reporting and detailed black-and-white illustrations, Sacco brings the conflict to life through the stories of ordinary people. I was also reading the book as a journalist would and it struck me that honesty, empathy and self-awareness are the keys to the profession, whether you tell the story with or without the pictures.

Understanding Comics

Who’s the author: Scott McCloud: McCloud started as a cartoonist and comics book writer, and is now a hugely respected comics theorist

What’s the book about: If Hillary Chute’s Why Comics, gives us a sense of the history and cultural significance of comics, Understanding Comics, written as comics, opens the hood, reveals the engine, the intricate network of hoses and belts and explains how it all works. I read it along with its sequel Making Comics, and felt much better informed.

When I mentioned these two books to a friend, a comic buff, he said I should be reading actual novels instead of these ‘explainers’, because all this theory will corrupt the raw experience of reading a novel. "Instead of enjoying, you will be analysing these books.” My experience however has been different, as I explained in the intro. I sent this Richard Feynman video to him.

Next steps

The list is just one way to start your journey, the one that I followed. I gravitated to these books because of my own interest in journalism and storytelling.

But there are many other ways to start your journey.

Lifelong learner: Check out the The Cartoon Introduction series. I especially liked The Cartoon Introduction to Economics by Yoram Bauman and Grady Klein.

Non-reader: You want to read books, but end up not reading them. There are graphic novel versions of some famous books. I recently read the two volumes of Sapiens. They were pretty good.

Movie buff: There are movie versions of graphic novels, like Persepolis. But you might also want to check out American Splendor, at least for the brilliant performance of Paul Giamatti. It's here (YouTube link).

Just jump in.