[Observation deck on the Ocean Albatros. Photo courtesy Albatros Expeditions ]

The North Pole captivated Western imagination for most of the 19th century. Its enigmatic allure spurred fantastical theories, like the one proposed by John Cleve Symmes, a former US Army officer, who believed the poles were Earth's hollow entrances to a nested world system. In 1885, Rev William F. Warren, president of Boston University, published a 500-page tome titled Paradise Found, claiming the polar opening led to the Garden of Eden. He described the aurora borealis as an expression of inner Earthly purity, and asserted humanity's natural draw to the pole as a yearning for “an abode of unearthly and preternatural effulgence, a home fit for gods and holy immortals.” (Ninety Degrees North, Grove Press, 233)

While the past two centuries have demystified much of the North Pole, it still remains one of our planet’s final frontiers, enticing travellers seeking more than the usual tourist fare with expedition cruises. Expeditions offer a rawer, more uncut experience of the wilderness, yet with the relative comforts of a modern cruise. Near the poles, this translates to a loosely planned route, with the expedition crew and captain collaborating to maximise wildlife sightings and landings via ship cruises, Zodiac excursions (motorised rubber boats for around 10 passengers), and ground explorations. Expedition itineraries are inherently dynamic, especially in the High Arctic, where weather and the presence of certain wildlife (think: enormous, furry, white, and seal-loving) necessitate a flexible landing approach.

Our journey to the Arctic began at the end of June with a flight from Oslo, Norway to Longyearbyen, one of the world's northernmost permanently inhabited towns and the main settlement in the Svalbard archipelago. Svalbard itself is a pearl of the far north, about halfway between Norway and the North Pole. The archipelago is almost 60% covered with glaciers and ice caps and surrounded by sea ice most of the year. The land has excited curiosity for ages, attracting explorers, miners, hunters and tourists enchanted by the Arctic. Pomors, Russian trappers from the White sea region, travelled for the rich haul of skins and pelts. Dutchman William Barentsz discovered Svalbard in 1596 while trying to find an alternative passage to the eastern spice lands, and met his end after being stranded during his return voyage.

[With my mother, Cuckoo Paul]

Though the focus of an expedition is less on luxury and more outward, you’re still not roughing it like Roald Amundsen on the Fram in 1910, the ship that helped secure his discovery of the South Pole. Enter the Ocean Albatros: a sleek, 341-foot ice-strengthened (Ice Class 1A, capable of breaking through metre-thick pack ice) expedition vessel launched in 2023. This seven-deck marvel boasts multiple observation decks, lecture rooms, two restaurants, and cutting-edge sonar technology for detecting floating ice. The Ocean Albatros was the perfect platform for those of us who yearned to follow the footsteps of explorers without the hardships of scurvy, frostbite, and hungry polar bears.

[The Ocean Albatros. Photo courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

The expedition staff met us at the Longyearbyen airport and whisked us to the pier for our Zodiac transfer to the ship. Safety briefings commenced immediately, with the staff instructing us on proper Zodiac boarding and disembarking techniques, emphasising the “sailor's grip” for secure entry and exit.

[On a Zodiac. Photo courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

Upon boarding, we were directed to the Shackleton lecture room, where we were welcomed by Diego Punta Fernandez, our Argentinian expedition leader who apart from being an avid birder, also runs a publishing company that produces several guides of flora and fauna of Patagonia, Antarctica and the Arctic regions. He introduced our guides, a team of geologists, marine biologists, ornithologists, and other Arctic experts. Next, our lead guide and Rifle Master presented a comprehensive safety briefing for off-ship excursions. It became abundantly clear that Arctic exploration wouldn't be the leisurely tour one might expect on your usual summer holiday. Unlike Antarctica, Patagonia, or other destinations where independent exploration is common and wildlife more abundant, expeditions in the Arctic necessitate a wholly different approach. The key differentiator was the presence of the Ursus Maritimus, or the polar bear, the very animal we’d come halfway across the world to see!

The polar bear is the apex predator of the Arctic and one of the few animals in the world that consider humans as potential prey. Which is why before any landing, the expedition team would spend a couple of hours scouting the area, first from sea and then on land. A handful of expedition guides armed with flare guns and rifles would form a large perimeter around the area we’d be exploring, a sort of protective bubble inside which we could explore our surroundings with relative freedom. The idea was to only ever encounter a polar bear when we were on sea, and it was on land. Meeting one on land would lead to a high probability of confrontation with this magnificent marine mammal and potentially force the expedition team to shoot at it in a worst case, completely avoidable scenario.

Diego consistently emphasised the importance of flexibility throughout the expedition, explaining how his team prepares numerous backup plans and routes to adapt to situations where our primary objectives become inaccessible. “We don't just have Plan A,” he declared, “but B, C, D... and when the letters run out, we move on to numbers!” We all smiled when we heard this but his words would come to characterise most of our days on the Ocean Albatros.

Leaving Longyearbyen, we set sail for Burgerbukta, a scenic bay in Hornsund fjord. The vibrantly coloured cliffs lining the bay displayed a geological history laid bare — I could even spot red streaks of iron ore! Our initial plan was a landing, but the expedition crew's inspection revealed tides too shallow for a swift Zodiac evacuation should it become necessary. So, embracing the adaptability that's the lifeblood of expeditions, we switched gears and embarked on a Zodiac cruise instead, soaking up rare Svalbard warmth. Summer in the High Arctic means no sunrise or sunset, with the sun high up in the sky moving only a few degrees. Temperatures though can be chilly because of the latitudes.

[Zodiac at Russebukta]

Our Zodiac guide, Mikaela, was a remarkable woman. A member of the history-making all-female crew that sailed a yacht around the world in 1989 (source), her expertise shone through as she expertly navigated us close to the edge of the pack ice. There, we had our first sighting of the local wildlife — a harbour seal casually navigating its icy domain. The towering cliffs provided a haven for countless birds like Kittiwakes and Guillemots, their calls filling the air whenever the Zodiac engine fell silent.

[With Mikaela, our Zodiac guide. She is a member of the history-making all-female crew that sailed a yacht around the world in 1989]

The Ocean Albatros, beyond its offerings like a library, open-air jacuzzi, and restaurants, also boasted an ‘open bridge’ policy. This meant guests could visit the bridge, the ship’s nerve centre where Captain Arsen Prostov and his team chartered our course. During the Captain's welcome, we raised glasses of bubbly to toast a successful voyage. Our laconic, 35-year-old Ukrainian captain humorously confessed he'd considered using ChatGPT to craft his speech, but decided against it, fearing AI might not just write his speeches today, but one day “start steering my ship!” We eagerly signed up for the first bridge tour offered.

On the bridge, Captain Prostov patiently explained the array of control panels — from SONAR and navigation to stabilisers, door access, and communication. When a question arose about the Ukrainian war's impact on the multinational crew, he maintained that everyone maintained a congenial atmosphere onboard and political differences were left on land!

[The captain at the bridge. The Ocean Albatros has an ‘open bridge’ policy]

As our bridge tour neared its end, perhaps sensing some of us glazing over details of stabiliser control, our Captain, with a twinkle in his eye, asked, “Shall we take a little detour into the ice?” On an impromptu decision and to loud cheers, he steered the Ocean Albatros into the pack ice, offering us a rare chance to witness firsthand what the ship was built for!

Crushing through sea ice, off the island of Edgeoya, was an unexpected bonus. Few cruise ships possess the reinforced hulls to navigate these conditions. Excitement crackled through the bridge, a shared thrill between passengers and crew. The elegant and powerful X-BOW (an inverted hull that challenges conventional perception of how ships should look) of the Ocean Albatros, sliced through the drift ice, meeting each icy obstacle with a dull thunderclap. The few non-military vessels capable of such feats are mostly former research ships or dedicated icebreakers.

The atmosphere on the bridge had intensified markedly. Captain Prostov issued crisp commands to his first officer and the midshipman as he steered our 8,000-ton behemoth through the icy gauntlet. Despite the biting wind and bone-chilling cold, for the 100-odd passengers, this was an unforgettable experience. Most of us braved the elements on the fore deck, retreating inside only when the cold became unbearable. Edgeoya, the archipelago's third-largest island, sprawled out before us, its carved cliffs sheltering numerous bird colonies. To the east, the vast ice cap stretched towards a 60 km sea front, while the south opened up into a seemingly endless plain.

The next day found us in Storfjord, a majestic expanse of water nestled between Spitzbergen, Barentsoya, and Edgeoya. Here, under the sharp glow of the evening sun (if “evening” is even the right word!), I had the chance to kayak amongst the ice floes. It was my polar paddling debut, and the mandatory wetsuit served as a chilling reminder of the frigid waters — one of our guides helpfully pointed out during the man overboard drill that without proper gear, survival time wouldn't exceed 40 minutes.

[Kayaking amongst the ice floes. Photo courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

We hopped on a Zodiac, kayaks in tow, and headed towards a cluster of islands and ice flows in the distance. Our guide, Jordan, a Canadian, revealed how the polar regions had bewitched him on his first trip years ago, prompting him to sell most of his earthly possessions and become a guide. A quick safety briefing followed, where the dos and don'ts were covered (One American's enthusiastic suggestion — to outrun a polar bear by hamstringing your neighbour — elicited a dry chuckle). In his bright red kayak, Jordan led us on a navigation through the icy labyrinth, while regaling us with tales of his adventures. Both Jordan and our other guide constantly kept a watchful eye for bears and walruses. Jordan schooled us on the greater threat walruses posed in kayaks due to their territorial nature. He recounted a story of an Inuit friend who, while kayaking, was charged by a walrus! The tusks of this one-ton behemoth narrowly missed his thighs, piercing right between his legs and into the kayak. Needless to say, this anecdote kept us close to Jordan, which proved fortuitous when one of the team spotted an Arctic fox on the hunt!

Jordan explained that while the fox we saw was predominantly white, their coats change with the seasons. It's not uncommon to see them mid-transformation, resembling a pair of disembodied brown front legs running in the snow with a white, camouflaged rear! The effects of global warming, however, are disrupting this natural cycle. Melting ice means foxes can get caught with the wrong coat, hindering their hunting success.

[Lectures at the Shackleton Lounge]

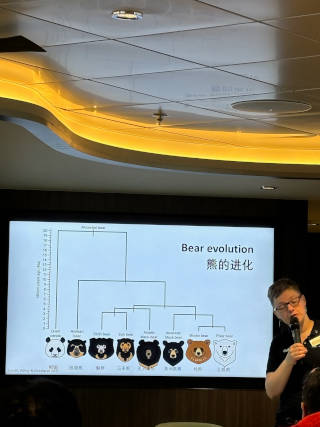

The abundance of lectures offered by our expert guides was a chief perk of our expedition cruise. Mostly held in the Shackleton Lounge, these talks covered a fascinating range of topics — the region's geology, Svalbard's history, the diverse birdlife of the Arctic, mastering binoculars and animal spotting, and even polar bear behaviour and physiology (interestingly, polar bears are edible, except for their livers. The high concentration of Vitamin A is fatal to humans, as many early explorers found out!)

Day three finally brought our first landing — Andreetangen, a long, narrow strip of land jutting out from Edgeoya's southwestern corner. Steeped in history, the site has likely been frequented by hunters and trappers since the early 1800s. A hut built in the 1940s by the legendary Norwegian hunter Henry Rudi (best known for having killed a total of 713 polar bears) still stands, surrounded by a scattering of bones, some more recent than others.

[Norwegian hunter Henry Rudi’s hut. Photo courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

Stepping from our Zodiacs onto land, we were greeted by a dramatic landscape — a stark marriage of windswept tundra and tortured rock. Life clung on tenaciously; no trees grew here, not even a blade of grass dared to sprout. This was a realm of rock, wind, and cold, a world only the highly adapted Arctic flora could truly call home. Lichens, growing a mere few centimetres per decade, subsist on minerals, enduring the land's icy grip for most of the year. Despite the harshness, there was a stark beauty in the quiet stillness, the remoteness, the icy minimalism.

[Flowers grow even in this extreme land. Photo courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

Svalbard reindeer grazed peacefully nearby, their millennia of evolution in a predator-free environment (unlike their relatives elsewhere) rendering them unconcerned by our arrival. Recent reports, however, suggested that this was changing. With dwindling sea ice, their preferred hunting grounds, polar bears have begun turning to reindeer as a food source. However, some of these reindeer lay down on the tundra, seemingly unfazed by our presence.

[Reindeers at Svalbard]

Close by was Rudi's hut, and beyond that, a large haul-out of walruses engaged in their usual shore-side activities — lounging, sleeping, and farting (for the more curious among you). A young calf among them necessitated keeping a safe distance, per Arctic regulations. We didn't want to startle the walruses and trigger a stampede, which could result in the calf being crushed by the adults (interestingly, this is a hunting tactic polar bears use — by causing a stampede, they can incapacitate the young walruses, as the formidable adults are too much to tackle). Since day one, the expedition crew had emphasised the importance of leaving the Arctic exactly as we found it. This meant introducing nothing foreign to the environment and taking nothing away. Which was a pity because I found an old, spent rifle shell on the ground which might have made for a cool souvenir!

[Walruses doing what they do best on shore. Photo courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

The next day, lunch was interrupted on what was to be the most thrilling day of our journey by an announcement over the ship's PA system: a polar bear sighting! Excitement crackled through the air as guests, crew, and even restaurant staff rushed to the outer decks, binoculars in hand. A group of islands lay a few hundred metres away, and there it was — the magnificent creature we'd all been hoping to see! The captain tried to get as close as he could in waters that were very poorly charted so that we could get a better look. Fortunately, the large adult male polar bear also seemed curious and began making its way closer to us, casually swimming in the choppy water and making short work of the distance. Once on the main island, it kept raising its head and tasting the air (a strategy it also uses while hunting, where it walks perpendicular to the wind and tries to catch scent of its prey from as much as 20-30 km away) to make sense of our ship and its strange and unfamiliar scents. Just when we thought things couldn’t get any better, we saw a second polar bear come into view from the far left of the island. This was a smaller male, which kept respectful distance from his larger companion for a brief period before deciding it’s best to avoid a confrontation and swam away.

[A polar bear sighting. Video courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

The exhilaration on the decks was palpable as many of the guests and crew brought out cameras that resembled small cannons and had a field day shooting pictures of the bear as it foraged through bird nests on the island. Angry Skuas kept dive-bombing the bear to ward it away from their nests but found themselves slightly out of the half-ton male’s weight class. Polar bears have among the most advanced sense of smell among all mammals and there was no way it would miss any eggs on the island. We later learnt that a few such bear visits to the same island during bird mating season all but decimates any potential for offspring. After scouring the island, the bear finally disappeared on the far side and we departed happy customers.

Back on the ship we got to know our co-passengers better. The daily expeditions on the Zodiac and transits via the ‘mud-room’ and the wondrous sights bound us together, a clutch of nationalities and families. The scenery was so otherworldly and could make us feel emotional, including the one time Captain Arsen anchored the ship right alongside a massive glacier overflowing into the pristine blue waters, just in time for a lunch barbeque served on the outer deck.

[The ship’s stateroom cabin]

Two animated groups from the US and China had a great time. The spectacular backdrops offered great photo-ops, and our fellow travellers had come prepared with arctic animal costumes and one in full Viking gear! We laughed at the howls of protest when the expedition leader called off the ‘polar plunge’, a bucket-list event where passengers have a chance to dive into icy waters with a tethered harness. They said it was for logistical reasons, but rumour on ship was that the plunge was called off because some from the group wanted to do it in the buff!

We snagged Diego, our expedition leader for lunch one day, eager to pick his brain about the future of expedition travel, conservation efforts in the Arctic, and the intricacies of his job. All through our cruise, we had woken up to the Argentinian’s pleasant ‘Good morning Albatros’ broadcast to the ship at 7 am, when he roused us and outlined any morning landings. Balancing tourism with environmental protection remains the biggest challenge, he admitted. How can we ensure the long-term health of the Arctic’s wonders as expedition cruises gain popularity? New regulations slated for the following year might restrict the maximum number of passengers on each ship. Cruise lines also adhere to strict protocols established by the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO). This self-governing body ensures that only one ship visits a specific location at a time, with schedules planned months in advance.

Diego's concerns resonated deeply with us, especially as travellers from India. We understood firsthand how overcrowding and mismanagement can mar the beauty of our national parks. Tour operators often prioritise profit over sustainability, leading to a classic tragedy of the commons scenario. Thankfully, the pristine beauty of the Arctic stood in stark contrast to our experiences back home. However, it isn't immune to the consequences of human actions. Every year, the warm North Atlantic current carries tons of waste, primarily plastic byproducts from the fishing industry, to the Arctic. This stark reminder of our global consumption habits cast a momentary shadow on the otherwise upbeat atmosphere.

One could easily succumb to a sense of despair in the vast emptiness of the Arctic, as even the great explorer Fridtjof Nansen pondered during his polar push in the late 1800s: “If, after all, we are on the wrong track, what then? Only disappointed human hopes, nothing more. And even if we perish, what will it matter in the endless cycles of eternity?”

Thankfully, my own bout of melancholy was short-lived. Initiatives like Clean Up Svalbard offered a beacon of hope. This programme encourages cruise lines to collect debris found on remote landings, with crew and even guests participating in waste removal efforts. Each summer, Clean Up Svalbard removes around 20 tons of waste from Svalbard's beaches! I’m certain that most of the expedition guests will leave the Ocean Albatros more aware about the delicate balance of life in the far reaches of the world and some will hopefully begin to make a difference, in whatever small way they can.

At the Captain’s farewell, the mood was decidedly cheerful and the travellers were content with the sights and sounds they had experienced in their five days aboard the ship (the glasses of champagne didn’t hurt either!) We joined in the chorus as one of our expedition guides and musician, Kevin Closs sang The Polar Bear Bar Song, one of his own compositions. We then cheered on the entire ship crew and expedition staff in a broadway style curtain call before it was time to retire to prepare for an early disembarkation the next morning.

[Soaking in the view]

For me beyond the Arctic's wonders, this trip unveiled a new dimension of travel — expedition cruises. They seamlessly blend sightseeing, adventure, education, and responsible tourism. As this industry flourishes, I trust they'll find ways to share these marvels with a wider audience while safeguarding the very treasures they showcase to the world.

My travel tips

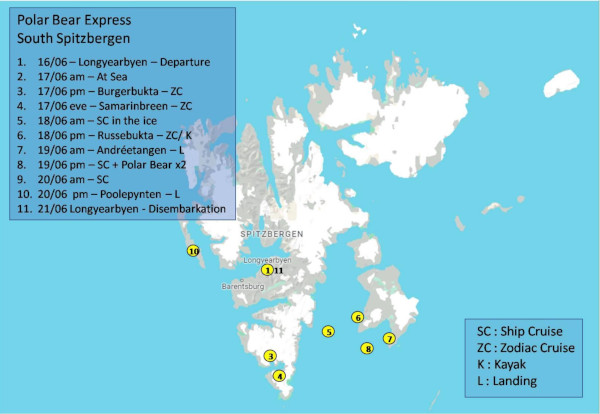

[A map of the places we covered. Courtesy Albatros Expeditions]

We are grateful to the crew and staff of Albatros Expeditions for the phenomenal experience and to our travel agents Unwild Planet for introducing us to this form of tourism.

To prepare for an expedition trip to the Arctic:

- As the adage goes, layering is key: bring thermals and a fleece layer to wear under your waterproof jacket

- You don’t need your tuxedo on an expedition ship, there is no dress code for dinner

- Bring boots fit for snow/rain (even though gumboots are usually provided by the expedition team)

- Waterproof trousers (the kind you might find at Decathlon or any similar vendor) are a must for Zodiac landings, the hem of these trousers must be able to fit over your gumboots

- Binoculars (even if they aren’t the fancy kind, these make a huge difference)

- Gloves (preferably water resistant) and a woollen beanie/muffler that can cover your ears

- Sunscreen and seasickness medication (if required)

- Sunglasses (optional)