["Two roads diverged in a wood..." Photo from Unsplash]

Every day we make decisions, carefully analysing from the options available to us and selecting a course of action. Our hope is that the selected choice turns out to be better than all the options we have rejected.

As the stakes get bigger, the errors from decisions can prove costly, for example, marrying the wrong person, hiring the wrong employee, not investing in a venture.

If we are going to spend our life making decisions, it makes sense to have some understanding of what kind of errors we can make and how to minimise them.

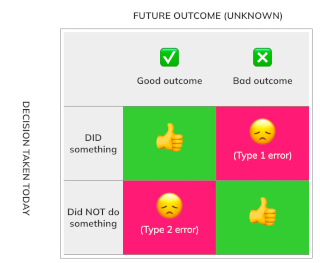

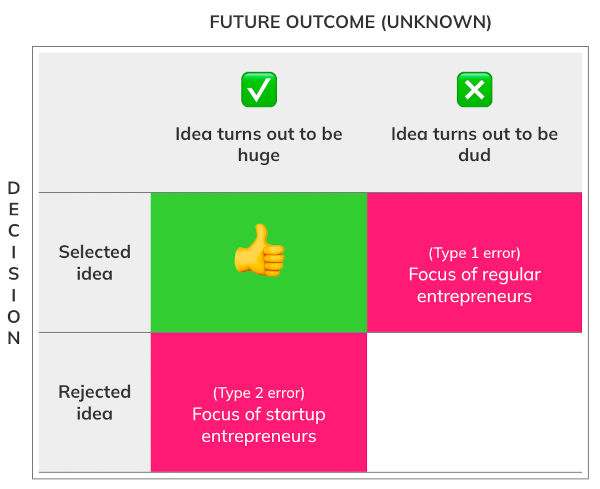

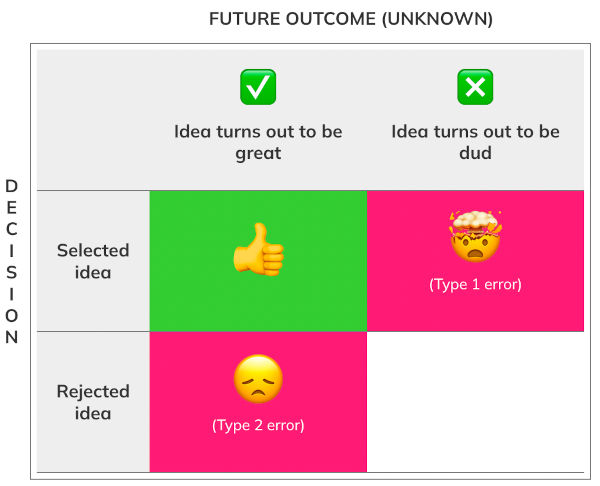

There are two types of errors that can result from any decision making:

First, when we commit on a particular option and that option subsequently turns out to be the wrong one. This is the error of commission (also called false positive or Type 1 error).

Type 1 error – Error of commission

We did something that we should not have.

Second, when we reject an option and, in hindsight, realise that this omitted option was indeed the right one. This is the error of omission (a.k.a. false negative or Type 2 error).

Type 2 error – Error of omission

We did not do something that we should have.

These errors can be put into an easy decision matrix like below. Remember that the decision is taken today while the outcome will be known only in the future.

These errors are explained in statistics as the acceptance or the rejection of the null hypothesis.

Example: When hiring for a role, HR wants to hire a candidate who is a good fit. The error they are trying to minimise is that the hired candidate turns out to be a misfit, i.e., the error of commission. However, in their filtering process they are bound to reject some good candidates (who may have possibly been far superior), the error of omission. But this is not their main concern.

By definition, errors of commission occur on the path we have decided to take, while errors of omission are on the paths that we neglected.

Theoretically, if we could select all the options available to us, we would not have any errors of omission. We would only have errors of commission.

On the other hand, if we reject all the options available, we would never commit errors of commission. We would only be faced with errors of omission.

If we attempt to be too careful in our selection (strong filter), we are increasing the chances of errors of omission. On the other hand, if we are not discerning at all, we are bound to increase the chances of the errors of commission. It is obvious that we cannot minimise both of these errors at the same time.

Armed with this basic framework, let us look at the process of decision making in different areas of investing, entrepreneurship, and in everyday life.

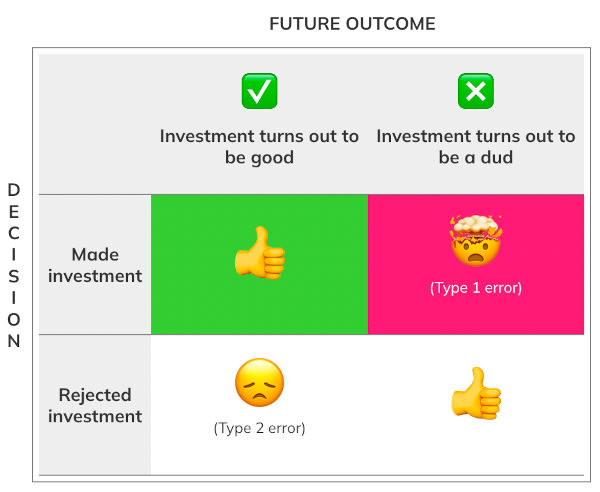

Individual investors

Let us take an individual investor who is salaried and is saving for her retirement.

Her investment objective is to save regularly (SIP) and create a healthy corpus for her life after retirement. Time is on her side and there are many decades for compounding to work.

Using our decision framework, which future error is acceptable for this investor?

-

Error of commission occurs if the investor creates a portfolio that later turns out to be sub-par or, worse, she loses her money.

-

Error of omission occurs if she misses out on great returns from potential multibaggers.

It is important to remember that capital is the raw material of investing, and once it is depleted, or worse, lost, the investor can be set back many years. It is evident that our investor must work to reduce the error of commission at the expense of the error of omission. The goal of the investor must be to generate returns that are positive and close to the market returns, rather than superior and unconventional.

One can go a step further and argue that the average individual investor should be invested in low-cost ETFs or mutual funds, and not venture into creating a self-selected portfolio of stocks.

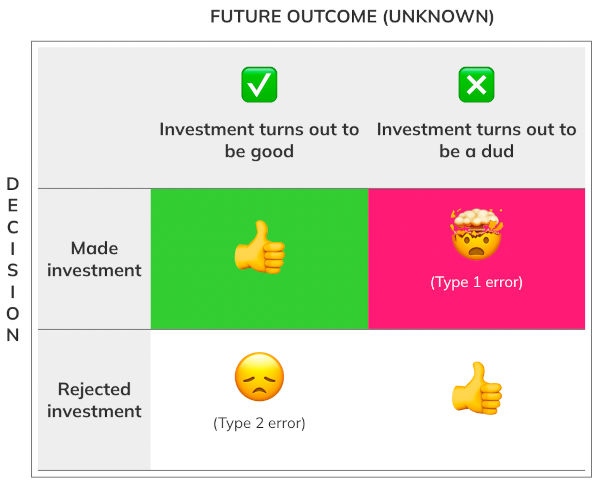

Fund managers

A fund manager manages other people's money as part of their professional job. The manager derives income from the fees that they charge the investors, which is typically a few percentage points fixed and/or a portion of the returns generated.

-

Error of commission occurs if the fund manager creates a portfolio that substantially underperforms the market index.

-

Error of omission occurs if he misses out on great returns from unconventional stocks and sectors.

On the face of it, it seems that the fund manager is likely to be more risk-taking as he is managing other people's money. But this is not true in practice.

If the fund manager selects unconventional stocks and ends up under-performing the broader market, it will endanger the fund as, (a) new investors will stop investing and (b) existing investors may also start redeeming.

To keep the steady fee income coming in, the fund manager has to ensure that the fund returns are never substantially lesser than the market and other similar funds.

“There are old investors, and there are bold investors, but there are no old bold investors.”

– Howard Marks

Fund managers that have survived are fully focused on the error of commission. They do not play to overperform. On the contrary, they play to not underperform. To ensure this, they create a baseline portfolio that consists of the most consensus stocks of the relevant index, and make only small tweaks.

Understandably, such a portfolio will shadow the market index, and thus this entire process is also called closet-indexing.

Fund managers’ compulsion to track the index has an interesting bearing on investors. In this light it is difficult to justify why a 2.5% management fee must be paid to an AIF (Alternative Investment Fund) or PMS (Portfolio Management Service) for buying some form of the market index. Unless a fund manager is willing to go contrary to the prevailing market sentiments, and has a track record of doing so, the average investor will always be better off investing in low-cost ETFs and direct mutual funds.

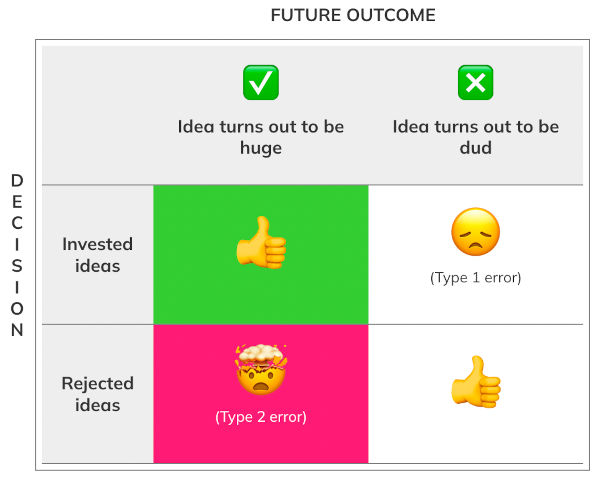

Venture capitalists

Venture capitalists (VCs) invest in young startups in the hope that they turn out to be the next Google and Facebook.

-

The error of commission will occur if the VC invests in an idea and it does not work out (or is very small).

-

The error of omission will occur if the VC does not invest in an idea and it turns out to be the next big thing.

VCs are paid by their investors to create large returns. A typical seed VC firm will invest in over two dozen companies out of which just one or two may possibly return their entire fund. However, most invested companies will fail or not go anywhere. Power laws are at play.

This is the reason that the VC does not focus on reducing errors of commission. It is okay if he invests in a company and it fails. What is not acceptable to him is that he rejects a company that later turns out to be the Google of tomorrow. The VC investor’s prime focus is on reducing the errors of omission.

VCs have even invented a word to describe the companies that they did not invest in, and which went on to become highly successful: the anti-portfolio.

Bessemer, a prominent VC firm in Silicon Valley, proudly lists these companies as its biggest misses.

They are regretting their errors of omission when they say, “If we had invested in any of these companies, we might not still be working.”

Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurs are of two types: those who run regular businesses and do not raise capital from venture investors, and those who choose to go into asymmetric areas and require to raise venture capital.

-

The error of commission occurs if the selected idea does not work out.

-

The error of omission will occur if our entrepreneur rejects an idea that may turn out to be very large tomorrow.

Regular entrepreneurs: For somebody who is running a design agency or a small software company, the focus is to have a sustainable business and cash flows, so that bills can be paid every month. It is generally not wise to put the base business into risk because of some bold all-or-none calls. The focus is on the error of commission and not on the error of omission.

Startup entrepreneurs: Consider somebody who has an audacious idea that, if it works out, can become very large. The risk-returns are off the charts. And yes, it will need VC funding to start with. The founding team typically has very high opportunity costs, and can always go back to a job should the startup not work out.

Like the VC, the startup entrepreneur is not afraid to make mistakes. What is unacceptable is that he wastes time working on something that is unlikely to become large, and there is no way that he can miss the next big thing.

The focus is on the error of omission as opposed to the error of commission.

This could be possibly why startups say, go big, or go home!

High net worth individuals

An HNI is most often somebody who made a windfall, possibly through entrepreneurship.

The HNI has dual motivations when it comes to investing. It is his prime consideration that his capital does not ever deplete or blow-up. At the same time, given his experience of making windfall returns, he would like to continue to be invested into asymmetric opportunities.

Note that these motivations are in complete conflict with each other.

The portfolio of a typical HNI will look like a mix of the regular investor and the VC investor.

-

Base portfolio: A majority (about 75-85%) invested in conventional equities and risk assets. These would be large-cap equities, bonds, property and so on. Very less risk is assumed here and the operative error remains the error of commission.

-

Satellite portfolio (about 15-25%) invested in highly risky assets: small-cap stocks, early-stage startups, crypto and such. This satellite is used to take large risks and provides optionality. Here the focus is on not missing opportunities which could turn very large, and it is known upfront that the many investments will most likely be written off.

No wonder most HNI investors are schizophrenic!

In our daily lives

In our daily lives, the people that we did not marry, the colleges that we did not attend—these will not be important if the choices we actually make turn out to be broadly alright.

Thus, our decision making must generally be focused on selecting options that are robust, and not the best ones. Our eye must be on errors of commission.

Having said this, the young should be willing to explore new things in life so that they have no regrets in future, what Jeff Bezos calls his “regret minimisation framework”.

So, if you are a young person, go ahead, become an artist, move to a new city or start your own venture. You never know what can happen when you walk the road less travelled by.