[From Unsplash]

Good morning,

All evidence has it that this is that time of the year when people start breaking New Year Resolutions. Data collected over the years from across the world has it that on average, most resolutions last between 12 and 26 days. That is why, when brainstorming, we thought this was as good a time as any to look at studies on the kind of resolutions people make, if it makes sense to make resolutions, why people slip, and if it makes sense to stick with it.

Let us know how it’s going with you.

To the year ahead!

Are New Year resolutions sensible?

January 1 sounds like an arbitrary date to make a New Year’s Resolution. Why not choose any day of the year to make a significant lifestyle change and get going with it? This question has been studied significantly over the years. While most studies suggest that while people fail, as ideas go, making resolutions is sensible. A recent essay published by the BBC places this in perspective.

“Psychologists have found that, rather than seeing our life as a continuum, we tend to craft a narrative, divided into separate ‘chapters’ that mark the different stages of our life. ‘People tend to think about life as if they’re characters in a book,’ says Katy Milkman, a psychology professor at The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, and the author of the book How to Change.

“Those chapters may characterise major life events—such as arriving at university, getting married or the birth of your first child. But your mind can also split those major chapters into smaller sections so that the start of a new year can represent a break in the narrative. ‘Any time you have a moment that feels like a division of time, your mind does a special thing where it creates a sense that you have a fresh start,’ says Milkman. ‘You're turning the page, you have a clean slate, it's a new beginning.’”

What resolutions do people make?

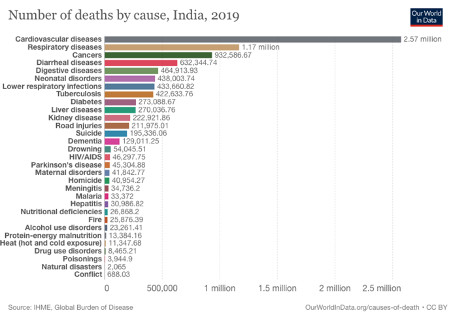

Given the circumstances and headlines that surround us, it is tempting to conclude that the most numbers of people lost their lives in recent times to Covid. But the data has a different story to tell. Ourworldindata.org reports the virus claimed 450,000 people in India alone. But this is the number of people digestive diseases claim each year. Cancer claims over 900,000 people and cardiovascular diseases kill at least 2.5 million Indians each year.

Hardly unsurprising that when researchers asked people about their New Year Resolutions, to get healthier and live better has consistently dominated people’s minds.

How to think about resolutions

If health and living better is top of mind for most people, on looking around, and our reading up on those who manage to stick to their resolutions has it that they work things backwards. This is an argument Dr Karl Pillemer, a gerontologist affiliated to Cornell University, makes. His research has it that when people are asked about how they would like to die, most of them answer: Quickly and painlessly. But the chances of that are remote.

“It’s not dying you should worry about—it’s chronic disease,” Pillemer writes in his book 30 Lessons for Living. Therefore, he argues, “the motivator should not be how long you live but how you are going to live. The person who reaches age 60, is going to live on average at least another 20-30 years. What you need to be concerned about is the quality of your life during that time.”

When extrapolated to how most Indians die, chances are high that most people will have to deal with some chronic disease or complications for years before they die. Common sense and medical practitioners say these can get to be protracted and painful affairs. Are these avoidable? While dying is certain, the pain can be avoided.

That is why Pillemer suggests, “If you’ve resolved to do something, stick to it.”

When do resolutions break?

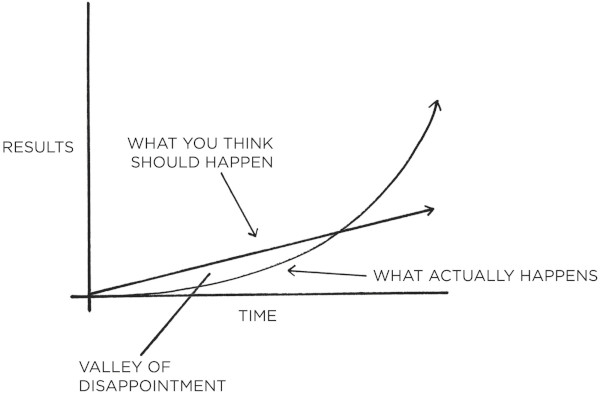

Like we said at the start, breaking resolutions comes easier than sticking to them. Just why does this happen? We want change to happen. It doesn’t. There’s this period when you go through the “Valley of Disappointment”.

This is explained well by James Clear in the bestselling Atomic Habits.

“Breakthrough moments are often the result of many previous actions, which build up the potential required to unleash a major change. This pattern shows up everywhere. Cancer spends 80 percent of its life undetectable, then takes over the body in months. Bamboo can barely be seen for the first five years as it builds extensive root systems underground before exploding ninety feet into the air within six weeks.

“Similarly, habits often appear to make no difference until you cross a critical threshold and unlock a new level of performance. In the early and middle stages of any quest, there is often a Valley of Disappointment. You expect to make progress in a linear fashion and it’s frustrating how ineffective changes can seem during the first days, weeks, and even months. It doesn’t feel like you are going anywhere. It’s a hallmark of any compounding process: the most powerful outcomes are delayed.

“This is one of the core reasons why it is so hard to build habits that last. People make a few small changes, fail to see a tangible result, and decide to stop.”

When thought about deeply, this is that time of the year when most people who have made up their mind are going through the Valley of Disappointment.

What happens if you stick with it?

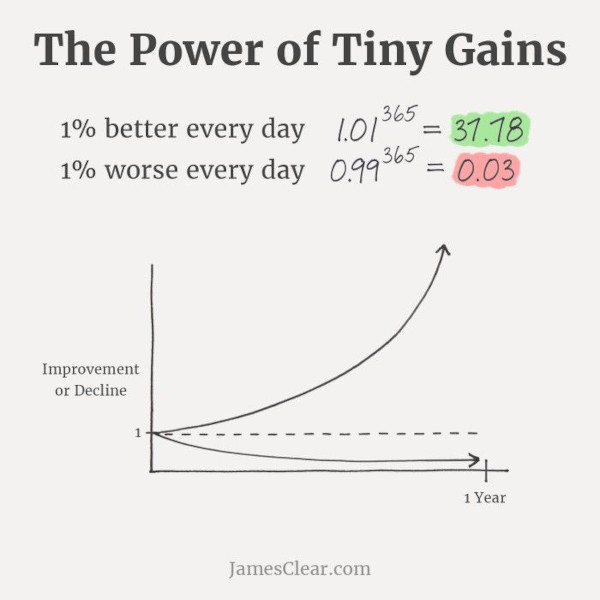

Not much needs to be said. James Clear did the math and plotted the exponential gains that can accrue over a year if a person breaks a resolution into small chunks and sticks to a plan for a year. He calls it the Power of Tiny Gains.

Does willpower have a role?

No.

To place that in perspective, for a long while, one school of thought has argued that willpower is a finite resource and must be used judiciously. Widely known as Ego Depletion, this is why at the end of a long day, people give in to cravings or find it difficult to focus on difficult things.

But recent research has it that this is bunkum. Kuldeep Datay, who practices at the Institute of Public Health (IPH) in Mumbai, belongs to this camp and argues that “Willpower is an emotion that can be generated.” Professionals such as him, however, face a problem in India. “Most people who visit me complain they have no willpower left. And I tell them willpower is not something you can purchase from the market. And when I ask those who complain, where do they think willpower comes from, nobody has an answer.”

This is where he steps in to counsel people that willpower can be generated. “Nobody complains that primary emotions such as happiness, anger or determination are precious resources and must be conserved. But it can be channeled to generate will power.”

Moral: Don’t give up on what you’ve started with.