By: Neelima Mahajan

Sometimes the biggest obstacle that stands between you and your goal is you and your wayward mind. You often start something new, but end up not finishing it. Think of the number of times you took a gym membership. Or vowed to eat healthy. Or decided on a career choice. What happened?

So why do we deviate from our well-chosen and well-thought out goals? Francesca Gino, a behavioral scientist and the Tandon Family Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, faced it herself: she started off intending to be an engineer. But since her then boyfriend was already studying to become an engineer and his mother thought that having two engineers in the family wasn’t such a good idea, she ended up studying economics instead.

Fascinated with this problem, Gino ended up researching it. She ended up finding the psychological drivers behind our inability to stick to a plan of action, and also ways to combat them. The result is Sidetracked: Why Our Decisions Get Derailed, and How We Can Stick to the Plan, a book that pushed Gino into the big league.

Excerpts from an interview.

Q. Why do most of us, however rational we think we are, end up making poor decisions?

A. Based on the research that I conducted in the last 15 years, I discovered three sets of forces that derail our decisions. The first is “the force from within”, and they are due to the fact that we are humans, and we come with emotions and we [have] biased judgments. The second set is forces from our relationships and these are forces to do with the very fact that not only are we human beings, but we are [also] social human beings and our relationships with others can actually get in the way of decision making. And finally there is a set of forces they I call “forces from the outside world”: the context in which we make decisions influence the way we decide and in particular, the context can provide pressures or other factors can come in to make us irrational.

Q. What are the psychological drivers that influence the choices we make? What roles specifically do mental shortcuts or biases play?

A. Mental shortcuts can be helpful in some situations, but most of the time, what we end up doing when we’re making decisions is we rely too much on these shortcuts and on our emotions and as a result, we don’t give the chance to our mental processes to use more deliberation and so we make poor decisions.

There is some beautiful work by Daniel Kahneman who looks at the types of processes we use when we make decisions. When we process information, there are two systems in our brain, which is a little bit of an oversimplification but it’s actually quite helpful to think about it in those terms. One is what you call System 1 and the other is System 2. System 1 is automatic, emotional, intuitive. System 2 is logical, it requires deliberation. What tends to happen with decisions is we like to latch on to System 1 and so we make all sorts of errors that lead to poor decisions. What we should be doing instead is engage System 2, and make sure there is more deliberation before we make our decision.

Q. You say that most people want to behave in ways that are consistent with their self-image, as competitive, effective and honest human beings. How does our self-image get in the way of decision-making? What implications does this have on the choices we make and the rights and wrongs of them?

A. We come to inflate our self-views. In class, I ask people to weigh themselves on a bunch of dimensions, such as their ability to make decisions, their ability to interact with others, and what I see regularly is that most people tend to think they’re better than average. This exercise shows that we have inflated self-views. We have very positive—too positive—views of who we are as individuals and what we can accomplish and the problem is that this will lead us to overconfidence that makes us focus too much on our own perspective of information and disregard what others can bring to the table. And this is problematic because this makes us reluctant to listen to the advice and opinions of others, when in fact, listening to them would lead to better decision making.

Q. What about people with negative self-images?

A. So there are people who are less confident than others, but in general, when you ask people to rank themselves against others on a bunch of dimensions such as honesty, decision making, their ability to negotiate, ability to get along well with other people, they actually think of themselves as better than others, so we tend to have a positive self-view.

Q. Are certain types of people more likely to get sidetracked?

A. It’s a question that I get a lot, and there are certainly individual differences that matter. However, all the tendencies that I talk about in the book are tendencies that we all show. It’s just a matter of how much of a push this factor needs to give us before we get off track. So it affects all of us for the very fact that we are human beings.

Q. How can we guard against our blind spots that derail us? What techniques should we employ to stay on track? Does motivation play a role at all?

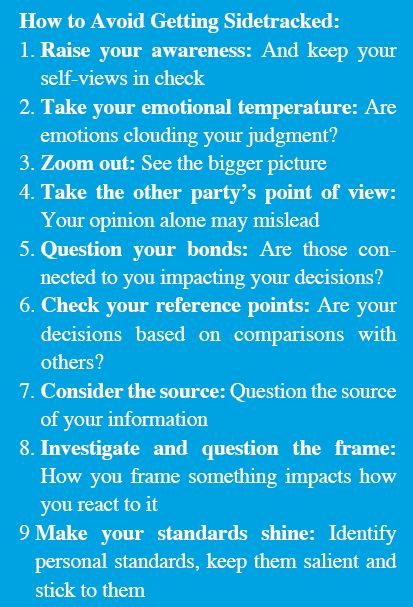

A. At a high level, we can do a couple of things. One, is being aware that these different forces come in easily and derail our decisions, and have the ability to recognize that biases not only affect the choices of others, but also our own choices. And second, having a checklist of questions that we can ask ourselves when we make decisions to be sure that we are not getting off track. For instance, one of them is taking our emotional temperature: making sure that we are in the right emotional state to make decisions rather than feeling too anxious, or too angry, etc. So it’s a little bit like having a checklist for a surgeon before they walk into the operating room, and being more thoughtful about engaging System Two when we make decisions.

Q. One of the things you talk about is zooming out in order to make good decisions.

A. Research shows how easy it is for us to be narrowly-focused in the sense that we just think about our side of the story or constraints that affect us, and we have a hard time taking a step back and looking at the problem from a broader perspective. So for instance, realize that constraints that affect us also affect the people who are working with us. One solution I propose is what we call zooming out: the ability to take problems and not get stuck in the details, but being able to take a step back and being able to look at the decision from a broader [perspective]… from a distance, from a higher level of perspective.

Q. Let’s shift gears to your work on getting employees to think and not just do. What implications does that have for job design?

A. One thing that I think would be very important for any employer to consider is in what ways they can allow for more flexibility and control in people’s jobs. And maybe the job doesn’t need to get redesigned, but what employees ask right from the start of the employment relationship is different.

Some of the work that we’ve done shows that if right at the beginning of the employment relationship, people come into the organization and get rewarded, if the company gives people space to think about their uniqueness and their strengths, how they could apply them to their jobs, people feel a greater sense of control and the potential to expand their strengths. They’re happier on the job, they’ll be more productive, more likely to stay with the organization. So, in that case, we didn’t change anything about the job per se, but people from the start have a greater opportunity to express who they are.

And similarly, in the cases we’ve done where we give people the opportunity and time to think at the end of each day, we didn’t quite change the job, but we created room for people to have the opportunity to spend some time thinking rather than doing.

Q. When you look at companies that do this well as opposed to companies that don’t is this defining factor?

A. So we have looked at companies that give people more time to think. Some companies, especially in the tech industry, are actually giving people some time off work so that they can work on their own projects and they’ve shown that this can lead to some innovation that is actually beneficial to you, beneficial in itself. I think that rather than changing the job, the job design, they change how the work is organized or designed so that there is a little bit more flexibility that comes into it.

Q. Can you give me examples of this?

A. Throughout the week, you spend some time on projects that you are interested in pursuing, and that might generate some ideas that are beneficial and that you can apply back to the organization. That would be one example. Or some companies allow employees to choose when to work or how to allocate their time to different activities, so that would be another way to allow for more flexibility.

Some organizations are very conscious of the fact that people need time to recharge because they can get exhausted when they are working really hard so they build in breaks that the people can take throughout the day. Those are ways in which I think the employers are being a little bit more thoughtful in how to structure the work such that you get the benefits of people being engaged and productive.

Q. So at some level, this is about flexibility and structure of work. But on a different level, it’s about me as an employee and my identity and how my contribution is being viewed within the organization.

A. Exactly.

Q. How should leaders evaluate their own behavior so that it doesn’t come in the way of employees thinking freely? Does this call for a very different kind of leadership style?

A. I think what they ask for is a different level of awareness and willingness from the side of leaders of asking themselves really tough questions in the sense of: “Am I creating the right circumstances or right context for people to be engaged and succeed?” I think that a lot of leaders have a chance to talk to the organizations but are pressed [for] time, and the first thing that goes when people are working hard and they have long lists of things to do, is the time to think about how to best develop others, motivate them, and dedicate time to ensure that you are giving them the right conditions for them to succeed. A little bit of time to think and make sure that they are providing the right context for people to succeed will be good on the part of leaders.

One company that comes to mind is Egon Zehnder. They are working really hard in terms of thinking about how to best assess their people and help them in their development. A few years back, they introduced a new model to assess and develop people called the Potential Model. They moved away from the idea of thinking of people’s competencies but rather assess their potential, which is not something that a lot of organizations focus on and do. Even if there is a gap in people’s experience, as long as they have the potential, which is a mindset towards learning, being curious, being persistent, then they can make up for that gap. It is particularly thoughtful in the way they think about assessing their people, creating the right circumstances for them to be engaged and to succeed, and making sure that everybody is on track and assuring that that is the case.

So if you look at, for example, the way even their partners are compensated for the work that they do, there is a lot of focus on benefits to the organization and the experience they have rather than just compensating people for the specific type of work that they’re doing, which would be too open to biases because maybe you are just working in a market that is very hot or on projects that are particularly important for and relevant across organizations. So they seem to be very thoughtful of creating the right circumstances for people to succeed.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]