By Venkat Sundaram

It was a bright, sunny and warm afternoon in Burnie in Tasmania, Australia, when the phone rang: Bishan Bedi was calling. After the usual pleasantries, he informed me that the visiting Pakistan team would be in Launceston to play a match, against Tasmania, and he would like to invite them for dinner. I said that it was a very thoughtful idea and asked how I could help.

He said that as he was about 70 kilometres away, that we would meet at my friend’s place in Launceston, and he would get the ingredients and some utensils. We would all combine our cooking talents and toss up something palatable. Bishan has always had more than a passing interest in cooking, and I was confident, having sampled his offerings, that the food would be more in the realms of delectable than palatable.

And what an experience it turned out to be! Here we were, three families, all hard at it—chopping, washing, marinating, frying, steaming, blending—for more than five hours. Often, as the available pots and pans were not large enough to cook for the nearly twenty-five guests, the same dish had to be prepared two or three times. Yes, it was some experience, but around seven in the evening, cooking was complete and all of us were quite exhausted. ‘Okay, now let’s get the drinks table ready and clean all the glasses.’ Bish, as we call him, was not done yet. It was an absolutely enjoyable ‘do’ with the affable Pakistani players, including several legends like Zaheer Abbas, Javed Miandad, Mudassar Nazar, Shafqat Rana and Iqbal Qasim. All were relaxed and at home, millions of miles away in Australia. There was laughter, jokes, toasts and stories. Above all, the quiet elegance and care of Bish was written all over.

I met Bish for the first time in 1971 as I made my debut in first-class cricket for Delhi. He was not available for that game, and I had to play against the then Ranji Trophy champions, Bombay—as they were then called—at the Brabourne Stadium.

Delhi were a ragtag team with no big names, with veteran Test cricketer Vijay Mehra as captain. Expectedly, the four-day match ended in three days—Delhi completely outplayed and Bombay won this game by 10 wickets. To a young debutant, the chasm that separated the two teams seemed insurmountable. While I was elated at having made a successful debut, the hurt and pain of losing without the semblance of a contest made me shudder. It was painful as I was always competitive and had my share of self esteem.

To see my seniors take a laid-back, defeated attitude hurt. ‘We are not so bad, are we?’ This thought plagued me as we made our way back to Delhi by train.

And while reflecting and recuperating from the thrashing, a steely resolve settled in. We must prove, one day, that we are as good, if not better, than the defending champions of the Ranji Trophy. ‘Defending champions’ sounded good. Would Delhi ever reach that level?

With this ‘fiery’ introduction to first-class cricket, and with tepid thoughts, I joined the pre-season practice nets at Feroz Shah Kotla grounds—and there was Bish, in his colourful patka, welcoming us. He had been appointed captain of the state side. ‘I did not readily accept the position; in fact, I declined it initially as I informed the then president of Delhi Cricket Association that I may not be able to comply with his views and this may lead to friction.’

How typical of Bish, and again, an introduction to his anti-establishment approach. He informed the president that he would like a ‘free hand’—a statement no administrator likes to hear while running Delhi Cricket. It was the start of a long battle with many subtle, and not-so-subtle, undertones that gripped cricket in Delhi, the North, and Indian cricket as a whole. ‘Put on your pads, Venks, and let’s see you bat,’ hollered the skipper. Delhi Cricket, until then, was usually a few warm-up stretches, a fifteen-minute net session and a few catches! Hardly surprising that the performance of the squad was deplorable. The first day with Bish changed all that. ‘You cannot be a match winner by batting for ten minutes. Keep batting.’ Music to my ears.

For the first time, I batted for half an hour, with the main bowlers testing me in every way. Most of the seniors were groaning after the first day at the nets as the session went on for nearly six hours. Extensive two-hour fielding sessions, lots of running and sprinting, calisthenics and stretching tested the fitness levels, both physically and mentally. The culture of this side slowly began to change. The old-timers were exposed and new blood was encouraged. Yes, there were ripples of griping but Bish would hear none of it. ‘If you cannot handle this, the door is open. Do something else that you enjoy.’

Bishan was from Amritsar, in Punjab. Cricket in the North, from partition days, revolved around fast bowlers hurtling down their pacy deliveries on matting wickets. Blessed with six months of cool weather, the hardy fast bowlers, tall and physically fit, were a real handful. Batsmen who were willing to work on their technique were a select few and most matches finished well within the time limits. Low scoring matches were the rule, the odd century or better, the exception. Spin bowling was so alien to their psyche that to see a crafty Trundler was sure to surprise and shock the viewers.

Bish was a graduate of Hindu College, Amritsar—an institution that promoted the all-round development of its students. It was here that Bish, under the care of his then mentor, Professor Gyan Prakash, got interested in the craft of left-arm spin bowling. He may not have had great icons to follow in his home state but India had a distinguished group of great spinners. The likes of Ghulam Ahmed, Vinoo Mankad, Subhash Gupte, and a number of first-class cricketers, like Salim Durani and Bapu Nadkarni, were already popular and well known. In this mix, Bish was making important strides and catching the eyes of men who mattered. His shift from Punjab, where he made his first-class debut as a sixteen year old, to Delhi, the National Capital that was pretty redundant in terms of cricketing, was a brave and life-changing decision. Moving from the extreme North to the centre would have, then, been a challenge, but Bish probably understood that Delhi would offer more opportunities and enable him to raise his stock and reach new heights. Despite its basic infrastructure, Delhi was where the Board of Control for Cricket was formed, and was one of the then five founding Test centres in the country.

Early in the piece, Delhi cricketers realized that playing for the state under Bish was not going to be a bed of roses. Far from it. The hard taskmaster that he was, Bish was a nightmare to the reluctant or the non-committed. He was fitness-driven; given his stocky frame and unathletic legerdemain, he realized that a physically fit athlete would add much to the team. It was an age where you learn by trial and error. Running twenty plus laps was a daily grind, followed by hours of catching practise. If that did not tire you, there was stair climbing and striding to follow. When you went into the nets to bat, it was normal to run three or run four, followed by a quick run two! ‘It is when you are mentally and physically tired that your concentration levels are tested. So, push yourself and see the results,’ he would say. Modern biomechanics and trainers would frown on such physical fitness regimes, but the first-class cricket season then consisted of very few matches unless the team qualified for the knockout rounds.

Bish was a very hard-working cricketer who never missed a net session and would bowl for five or six hours every day. He would often bowl to a single stump with a keeper standing well up. He would hit the single stump five times in six balls, time and time again. And no, he was not bowling armers but his natural flight and spin.

It was in such circumstances, under the wings of a master spin bowler, that we were moulded into a team of world beaters.

The early days were frustrating, as is usual, for the team limped visibly. The obvious limitations were glaring with the lack of depth in talent. So started ‘Operation Grab’. Quality players, mainly from Punjab, were lured to Delhi to strengthen the weak areas. Madan Lal, young, fit and a versatile all-rounder was the first to join, followed by the Amarnath brothers, Mohinder and Surinder. Both were talented and had fire in their bellies to set their sights higher. But, surely, the induction of Chetan Chauhan from Maharashtra to Delhi was the turning point. Chetan was a quiet, unobtrusive character whose batting was seeped in the Bombay school of batsmanship. He transformed the way cricket was played in the North.

Till then, Delhi batsmen, as Neville Cardus stressed, ‘reflected the times cricket was played in.’ A fiery stroke-filled 40 or 50, full of handsome shots and promising so much more, was usually cut short by a careless ill-thought heave or a run out. It was almost a given, and led to acrimony and frustration. Chetan, on the other hand, was a picture of concentration as he held the innings together. He was defensive, determined and unaffected by the events around him. Elegance and flamboyance, trademarks of Delhi batting was far from him. He was not bothered if he was beaten a number of times, but at the end of the day, he would be batting with a hundred against his name. ‘Learn to bat the whole day, and do not look at the scoreboard’ was one of his useful tips. Soon, Delhi batsmen learnt the art of building an inning and not throwing it away. ‘Take it as it comes, never give up’ was another useful sermon from him. Delhi was scaling heights and was being taken note of.

It was a Duleep Trophy match, between West Zone and North Zone, at Nehru Stadium, Pune, in 1973. West Zone was led by the then Indian team captain Ajit Wadekar, while North Zone was captained by Bishan Bedi. The two had sparred on the famous tour of England, where India won an away series for the first time: Bish felt he was under-bowled and made his thoughts public, leading to a lot of angst and bad blood. He even accused Ajit Wadekar of asking him to change his trajectory, and bowl flat and fast. To someone like Bish, this was sacrilege, and Bish said, ‘If you are not comfortable with the way I bowl you should not have selected me.’ This created, as you may expect, a storm in the media and the relations between the two were very frosty to say the least.

It was in this fiery atmosphere that the match was being played. North, the upstarts, were pitted against the West, the defending champions. It was like a boxing match and the atmosphere was bristling. In those days, a Deodhar Trophy one day match, played over 60 overs a side, preceded the three-day Duleep Trophy game. In the team meeting before the ‘one night stand’ as Bish called it, he stirred up the guys, saying, ‘Here is your chance to beat West Zone and get noticed. Man to man, you are all better than the westerners.’

Next morning, having lost the toss, North Zone were bundled out for 98 and West Zone romped home by 8 wickets! Well, we were beaten fair and square and, again, were no match for the more experienced team. We were deflated and hung our heads down. Noticing this, Gokul Inder Dev, a defence officer, arranged a visit in the evening to the military cantonment. A night of revelry and music helped relax the atmosphere and assuage the wounds of defeat.

There were two days left before the three-day match, and after the nets, a team meeting was held. Bish was always keen on team meetings; it helped clear doubts and stirred our confidence. At this meeting, he stressed that the big match was at hand, and that it was a new game. He mentioned again that as a team we should not be overwhelmed by the opponents. But it was after the stirring up, we discussed strategy that I mentioned that the toss played a big role in our defeat in the one-day game. There was early moisture in the pitch, and later with the hot sun beating down, the pitch rolled out to be a beauty. In those days, the skipper spoke and all listened. Also, Bish was a traditionalist who always stressed that if we won the toss, we should always bat first. It probably had to do with him being a spinner for, maybe, at the back of his mind, he knew the pitch would afford more turn as the match progressed. Not that he needed a square turner to make his presence felt. As it was, the Pune pitch was hard, and had a copious amount of green grass cover, something we in the North had never seen. Also, the West Zone team had the likes of Pandurang Salgaonkar, a raw, talented and extremely quick fast bowler in their ranks. In such conditions, he would be a handful.

A lot of steam was generated in the discussions, but Bish agreed to go along with the team sentiments, and it was agreed that if he won the toss, we would field. It turned out to be pivotal as the star-studded West Zone were bowled out for 248. The battle between Bish and Ajit Wadekar does call for special attention. West Zone, in seaming conditions, had a shaky start—losing their openers early. The medium pace of Madan Lal and Mohinder Amarnath was effective on the green top, and before the first hour was up, Ajit Wadekar walked in to a tumultuous applause from the Pune crowd. They were well informed and aware of the underlying tensions. And lo and behold, on a green top, and after the quicks had made initial inroads, Bish took up the challenge and wheeled in to bowl with three close-in catchers, and the others spread on either side of the wicket. Ajit, an attacking left hander, went for his shots and was into his 40s before you could wink.

It was then that Bish used his strategy, removing short leg to short midwicket, with three others in a wide arc between mid-on and square leg. He tossed one just outside off stump, Ajit lunged forward and on drove—a mighty blow—but straight to short midwicket where the catch was held. A jubilant Bish was thrilled but restrained in his celebrations. West Zone was bowled out for 248, Bish taking 4 for 81. North Zone also started shakily in the chase, and Pandurang was electric as he roared in and, on a helpful pitch, let it fly. But this was a determined North Zone team. The early damage was repaired and after a determined effort, during which the game ebbed and flowed, North Zone eventually took the vital first innings lead and knocked out West Zone. It was historic.

The North Zone was making its presence felt. Bish was achieving new landmarks. From now on, the image of cricket in the North will be changed forever. A mental hurdle had been crossed. In the Ranji Trophy, too, Delhi was taking new strides. There were many interesting clashes and Bish was always there, pushing and prodding us to new achievements. I particularly recall a few incidents that, on reflection, showed the charisma and talent of the team.

It was a match against Haryana where Delhi bowled out the visiting team for 207 runs. After tea, we had an hour to bat. The Haryana opening bowler was Kapil Dev. There was an experienced back-up in Ravinder Chadha, the great left arm spinner Rajinder Goel and a very crafty off-spinner Sarkar Talwar. In the 14 overs before close of play, with the light fading, Chetan Chauhan and I scored just 23 runs, but we were not out. I thought we had done well to deny an early breakthrough against accurate, testing bowlers. Well, when we entered the dressing room, there was Bish with his nostrils breathing fire. ‘Is this the way to treat this attack? They were not throwing atom bombs at you. We played like greenhorns.’ Well, all I could say was they bowled accurately, besides, we did not want to throw away our wickets. ‘Nonsense!’ and he went on, ‘Now, buy us a drink!’ So, that was that and we, Chetan and I, paid up.

The next day was ours. At tea, we had crossed 200 for no loss and eventually when I was out, the score was 252. ‘Well played, young man. That’s the way to go. And now you should celebrate the record score and buy us all a drink!’ So much for performance! We gladly celebrated with our teammates; and that is Bish for you—always goading you to excel, happy to share your success and raise your spirits, willing you to believe in your ability and aim for the sky.

Bishan, as a bowler, was always attacking. He was a bit of a gambler; this streak reflected in his cricket. He was always willing to buy his wickets, and tempt the batsman into an indiscretion. His methods were subtle, often giving away a few runs to lure the hapless batsman to his doom. I played a game with him when a top-order batsman came in to bat. He tossed a few deliveries, and the batsman enjoyed hitting a cover drive and an off drive for fours. The next over, the length was altered and the batsman had to stretch to reach the pitch of the ball. Then the ball was again flighted; but this time it spun a bit more, eluding the bat, and the batsman was stumped by a yard.

Bish went to the batsman, put his arms around his shoulders and said, ‘When a new batsman comes up against me, I check his grip and stance and after a few balls, I assess how many runs is the player capable of: 25, 50, or a 100? I then plan how to bowl to him.’ He also informed me that he enjoyed bowling at Perth and he enjoyed using the extra bounce to his advantage, as well as the notorious Fremantle doc. He took two 5-4 in the Perth Test of 1977–78, making it a 10-wicket haul.

It was in two matches that I particularly saw, at first-hand, the class of Bishan Bedi. In one of those games, I was a spectator, while in the other, a teammate.

The first incident that comes to mind was a Test match where India was playing against Bill Lawry’s team in Delhi. The Australians were very aggressive and talented. I was keen to see the battle between the Aussie batsmen and the Indian spinners.

It was breathtaking to watch the quick footed Ian Chappel and Keith Stackpole, not to mention my favourite, Doug Walters. The spinners were under the pump but they fought back. Doug Walters came in to bat and suddenly the crowd woke up to a stirring on-drive and a majestic cover-drive. Bish was bowling on home turf and coming under fire. How would he respond now?

In the second innings, I witnessed a piece of sheer magic. Bish went to the edge of the bowling crease and bowled an armer. Walters went back and across, expecting an orthodox spinning delivery. He shouldered arms but the ball, appearing to have a mind of its own, crashed and uprooted the off-stump. On the second occasion, Bish was captain of North Zone when, against Tony Lewis’ team, he similarly uprooted Barry Wood’s off-stump with an arm ball, the batsman offering no stroke. To reduce experienced top-order Test stars to fidgeting, nervous batsmen was in itself a reflection of Bish’s class. I asked him then whether it was the best arm ball he had delivered. He thought for a while before saying, ‘No, Venks. In England, with its heavy atmosphere, the ball moves much more, and my arm ball swings a lot.’

I once asked Bish how he rated Barry Richards, the South African batsman, and whether he enjoyed bowling against him. Bish said that Barry was a superb batsman, and pretty arrogant at the crease. ‘I was playing against him in Northants vs Hampshire. Hampshire had Gordon Greenidge and Barry as openers. Barry was striking the ball well, and they were off to a flyer. I was asked to bowl and the captain, Patrick Watts, asked me for my field. I said I wanted three close catchers, a slip, a short leg and a silly point.’ ‘Barry is on strike, so why don’t you take an additional fielder on the off side?’ the captain asked Bish. Bish suggested that he wanted to attack the batsman. The first ball saw Barry move out and play a cover drive for four. Again, the captain came to Bish and suggested an additional fielder on the off side. Again, Bish remained adamant. Next ball, same result once again and the same discussion between the captain and the bowler. The third ball saw Barry jump out of his crease, but this time, Bish got the ball to dip in flight and turn just that bit to beat the on rushing batsman and had him stumped by the proverbial mile. That’s Bish gambling and buying his wickets. ‘What’s 8 runs for Barry’s wicket?’ he said.

(Venkat Sundaram is an Indian former first-class cricketer who played for Delhi and Tamil Nadu. After his playing career, he became a selector for Delhi and pitch committee chairman for the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI).)

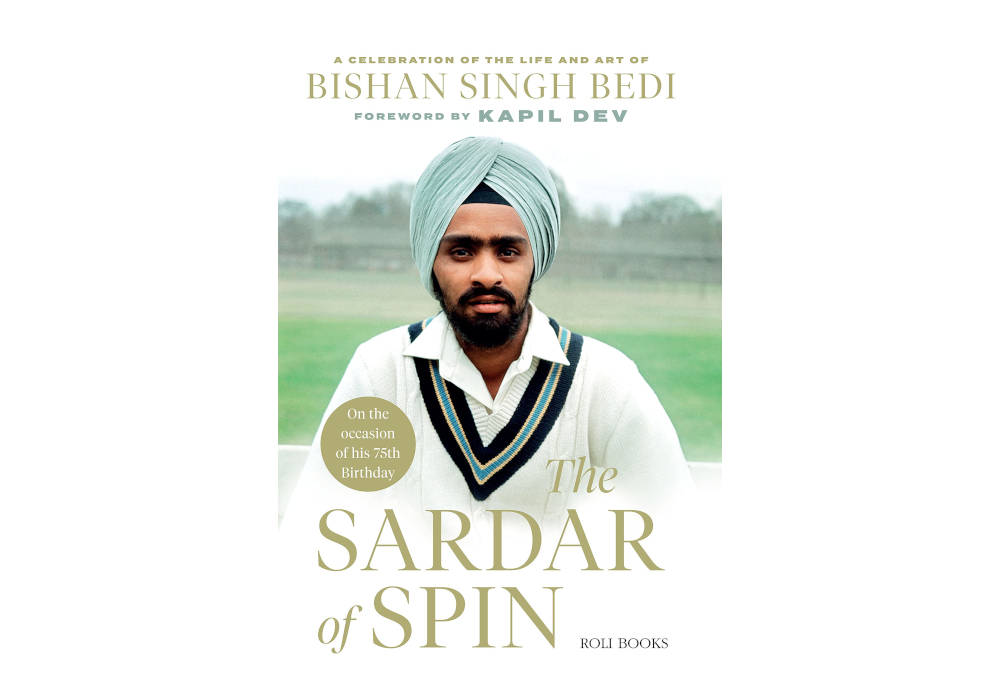

(This extract from The Sardar of Spin has been reproduced with permission from Roli Books.)