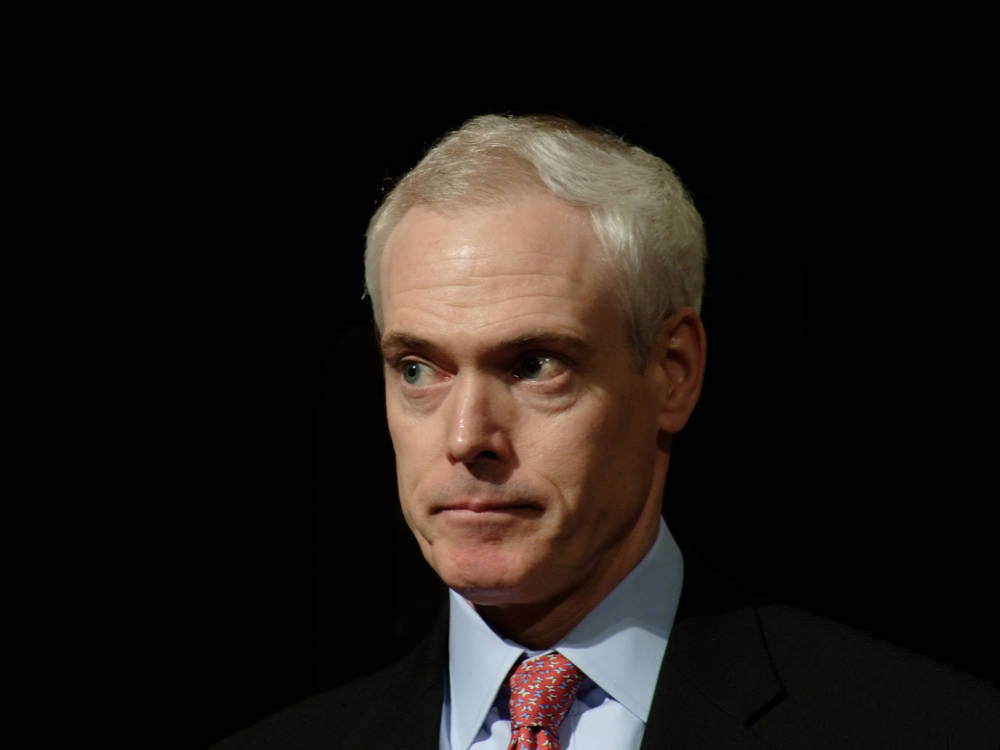

[Photograph of Jim Collins by Mangoed under Creative Commons]

By: Neelima Mahajan

What makes companies great? And how do you define 'greatness'? These are questions that management author Jim Collins has single-mindedly explored for nearly 25 years now. In 1994, Collins shot to superstardom with the near-explosive success of Built to Last, a book he co-authored with Jerry Porras. The book, which aimed to identify the characteristics of visionary companies by focusing on 18 of them, went on to become a management classic and was on Businessweek’s bestseller list for more than six years.

From there on, Collins authored several other books on the theme of greatness—such as Good to Great, How the Mighty Fail and Great by Choice. "This overarching question of what makes great companies tick just stayed with me for at least a quarter of a century," he says, talking on phone from his 'management laboratory' in Boulder, Colorado. "Each piece of work really became like another lens on this question."

Much as his work has created a profound impact on companies, it has also come in for some scathing criticism. Part of the reason is that some of the original 18 visionary companies Collins and Porras identified have slipped badly over the years, and people have questioned the very relevance of the principles he outlined.

In this very rare interview, Collins talks about the significance of his work today, the eternal quest to build great companies, how the shift from organizations to networks will impact leadership and much more. Excerpts:

Q. You say that instability is the historical normal. How then do you get the confidence to say that a business enterprise is 'built to last'?

A. I don't say which companies are 'built to last'. Instead what our work is about is principles that last. If you continued to live these principles with great intensity, they would correlate highly with the enduring of a great company. Imagine you were studying athletes. You can't necessarily say which of them are going to continue to be great athletes because if one of them [suddenly] doesn't train in the same way, loses discipline, begins eating badly, doesn't go to the track anymore, they're not gonna be great anymore.

I look at our work as studying historical dynastic eras. Think of it like great sports dynasties where some team achieved a world championship status that lasted for a significant period of time. In the US it might be like the 'dynasty' of the New York Yankees of the 1950s or the UCLA Bruins basketball team of the 1960s. We find companies that at a given moment or era were a dominant, dynastic enterprise. At that time [they] met the tasks of being truly great and we study them in that era. We basically say what principles were they living that were different than others in that era that were not great. It does not predict which ones are going to remain great or which ones are going to become great.

In Built to Last we were looking [at companies which had] at least a 50-year run and an iconic status. I can't guarantee that they're gonna [have] a 150-year run but we can learn from these 50, [in some cases 100], years of exceptional performance. Companies may come and go but the principles that would correlate with great companies at any time should endure.

Q. You wrote Built to Last in 1994 and after that global realities have changed. Would you say that the principles that you outlined 20 years ago still hold today?

A. First, we have not discovered everything. When I think about what you learn as you go along, I view it as additive, as the idea that that things you learn before don't get overturned but they're just incomplete. There's a big difference between what you saw before that was right but incomplete, as distinct from what you saw before that wasn't right. The beauty of the Built to Last study is that we were looking for principles that cut across easily when you add up what happened across time—as much chaos and change than anything we're going through today.

We have companies that were founded in the [mid to] late 1800s and the early 1900s, and they were able to become great companies and remain great through an extended period of time. [Between the late 1800s and the 20th century], we had two world wars. We didn't even have flying machines, instantaneous communication… microprocessors [or] transistors. IBM was getting started [and] it made butcher scales and time clocks. The idea of a computer wasn't even remotely on the horizon and you had massive social changes. Just take the amount of change that happened from the late 1800s up until the 1990s when we studied the Built to Last companies and through all of that change… the principles carried.

There's a second part to it: the duty of the historical analysis. If you can say why that principle was there in 1880, 1890, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970, 1980, 1990, then it certainly applies at any given moment in history. The second thing is let's take companies that are in the most turbulent environment that we could find in the world of business and we still have to have a rigorous way of looking at things, we still have to have some historical lens to know you're not just looking at a blip.

Q. If you were writing the book today, would the new list of great companies look any different?

A. Sure the list would be different if you were selecting it today. Let's go back to the definition of a great company: what is great and is it just defined by financials? I think you have to meet three external tests and they could come from anywhere. First, you have to have superior financial results, principally defined as return on invested capital over an extended period of time, at least a 15-year run of truly exceptional results when you do much better investing in that company than investing in the market.

But that's not enough, right? To truly be a great company, you can't have as your basic purpose, to make money. The companies that could endure understood this from very early on. The second output of great companies [is that] to be a great company, beyond the financial part, is a distinctive impact: I define it as if you disappeared… it would leave an unfillable hole. That's very different than just if you achieve great financial results—somebody else can just replace what you do, you've done nothing distinctive, you're not great.

The third is lasting endurance: you've the ability to be both distinctive and deliver of superior results. It means multiple generations of leadership and through multiple generations of markets and cycles and technology. Now it may not take very long to do the multiple cycles and technology or markets because they change so quickly. The critical one then becomes multiple generations of leadership and if you can’t demonstrate that you are able to be great through multiple generations, you're not really great. I like to challenge CEOs. If your company can't be great without you, it's not a great company.

Those three things—superior results, distinctive impact and lasting endurance. If we were to do [the book today] and we start thinking about it, okay, so let's just take some Chinese companies who [have] got superior results, distinctive impact, and they couldn't just be replaced by something else. They're not just copying and doing something cheaper, they would be hard to replace and [have] lasting endurance. Which ones have the ability to say, 'We’re not dependent on this leader we can do it with the next generation of leaders and the next after that'? When you look at a company like Amazon, it has a high return on capital, a distinctive role. If it went away it would really hurt, we don't know yet. [It’s got the] next step to prove it can do well beyond Jeff Bezos.

Q. Companies are increasingly talking of concepts like shared value and conscious capitalism. The financial crisis especially forced them to do some soul searching and redefine their purpose. Will this impact the notion of greatness?

A. Our research showed that those who build companies have a real shot at being great. They're not focused on building something to last, they;re focused on building something that's worthy of lasting and there's a big difference between lasting and being worthy of lasting. To be worthy of lasting means that you have to be built on a set of values. [These companies are] built on some sense of purpose that is not defined by economics.

R.W. Johnson first started thinking about this in the late 1800s and then his son, R.W. Johnson Jr., wrote it down in the Johnson and Johnson Credo in the 1930s: our first responsibility is to the patients, second to employees, third to the communities we affect and fourth to our shareholders. David Packard (Hewlett-Packard co-founder) said, the purpose of the Hewlett-Packard Company is to make a contribution, a technical contribution, that would make peoples' lives better and in order to do that, we must make a profit but we do not exist to make a profit, we exist to make a contribution.

They have this very deep set of values: I believe it is a moral responsibility that the people who help us create this company should share in the returns of this company and that we don’t make good quality products because of a marketing strategy, we do it because we owe that to people, to the people who trust us with the things that they obtain from us.

Bill Hewlett (Hewlett-Packard co-founder) said to me in this very grandfatherly way: "You know one of the very few key things in life, Jim, is never stifle a generous impulse." What a wonderful line! We don't have to choose between making a contribution and making money, between taking really good care of our people and having a really efficient operation, we don't have to choose about being responsible to the things that we touch and making sure that our company is well cared for. We're gonna be so good, so disciplined, so creative, so intense that we can do both and that is the standard that we are going to live to.

Our world is turbulent, chaotic and out of control, therefore it is all the more important that you have to know what your values are that you're going to use as a guidepost in that world or you're just gonna be ripped around in a world where people are searching desperately for a sense of meaning and connection and something that they cannot be cynical about and can throw their creative energies into and especially when they’re in networks as opposed to organizations. You have to preserve those values and pursue that purpose on one hand and stimulate progress on the other.

Q. You once said that we are moving to a world of networks well-led as opposed to organizations well-managed. What implications might this have on how our organizations are designed and how they function?

A. Peter Drucker [observed] about 60-70 years ago, we were becoming a society of organizations and that would be the building block of the world. Drucker observed the rise of the organization and then the rise of the importance of management to make those organizations work and the rise of the knowledge workforce. [Today] instead of the building blocks being organizations, the building blocks [are] networks and if networks are to the 21st century what organizations were to the 20th century, there’s another shift for organizations.

We had to think about management but for networks we have to think about leadership. Historically, we have been confusing leadership [with] power, personality, charisma, position. None of that is leadership. I've always loved what James MacGregor Burns said: "True leadership only exists if people follow when they have the freedom not to." Everything else is just power. Let's take General Eisenhower's definition of leadership: "Leadership is the art of getting someone else to do something you want done because he wants to do it."

It has three parts: you have to know what must be done; it's not about getting people to do it, if I have enough power, I can get you to do a lot of things, [but] to get you to want to do it; and finally, it is not a science, it's an art and all of us have different forms of artistry… [and] maybe our artistry is [about] how to get the right people in a room and asking each one the right questions.

Let's move to what networks require. [In] networks, you cannot rely upon position and power in the same way. The only way to organize is you genuinely have to lead. That would put a premium more on the sense of how do I get people, over who I do not have power, who are connected and dispersed, to want to do what must be done. That would be leading in a network as opposed to managing in an organization.

Wendy Kopp, founder of Teach for America and now Teach for All, is [taking] the Teach for America concept of getting young people to commit themselves to serve in our most underserved schools and to really help as many kids as possible get a great shot in life by that initial education. She's now taking it to the rest of the world, as much as she can [by] building a network. She has no power over kids to get them to sign up. She has no power over all the different places in the world where she’s getting people to try to form these units to make this happen, but she's building a network and she's building momentum in that network. She's not a personality-type of leader, she's just a very authentic leader [who can] get hundreds of thousands of people to sign up to want to do what must be done. That is a marvelous example of a network well-led, as opposed to an organization well-managed.

Q. So these leaders need to be authentic leaders, but what else should they have?

A. In Great by Choice, [we say] the more that you have [the] chaos of a network, the more, in fact, you have to have fanatic discipline. It's so easy to get pulled in so many directions, if you don't have your sense of what marches you need to be on, so that you can stay focused on that march and not get pulled in a gazillion different directions. The second is, it's not about innovation.

A lot of companies have innovation. What's really hard is figuring out which innovations will actually work and which of those innovations to scale and make big. So this ability to have an empirical kind of creativity, to say in the melee that’s out there, it's actually tough to [predict] what actually works out. You fire the bullet to figure out what will work, but then you need to scale it, turn it into that big cannon ball. Your ability to scale an innovation and make it really big is really the distinctive capability. The third is productive paranoia: in a world that is networked and could be moving under your feet all the time, the need for tremendous vigilance to be able to absorb the unexpected shifts and shocks means having great financial discipline and conservatism because you don’t know what might come tomorrow, as we found out in 2008.

The other [part] is what I learned in our study of leadership at the United States Military Academy at West Point. I went there to teach leadership but actually ended up learning a lot more. I stepped into an environment where people were so committed to what they were doing [that] I found myself thinking about what makes this tick. I began to realize [there is] a triangle: service, growth and success are the three points. The only way to really be exceptional is at some point you're gonna fail a lot and to view those failures as the opposite side of the coin of success is not failure, it is growth. It is the ability to throw yourself at things that are going to make you fail and then through that to grow and become stronger because if you aren't able to do that, the [vicissitudes] of our world [will] crush you.

But then why would you really go through this failure to growth? There's this thought that there is this tremendous ethic of service. And a sense of I am in service to something. I am giving my [service], in their case service to country and service to comrades, to each other. And a tremendous ethos of 'this isn’t about me, this is about service to cause, and to the men and women around me'. To really thrive in the kind of world we're heading into, that sense of what you do in service is the only way you can activate those around you over whom you have no power. Because if they don't think you're in service, why should they be in service?

What I came away with from West Point was the idea of communal success and the idea that you only succeed by helping others succeed. I was training for the Indoor Obstacle Course Test and the [cadets] were helping the old man try to figure out how to do it. Every cadet has to do it in a certain time period or you don't make it through West Point. Classmates [were] taking time out of their busy schedules to help their classmates accomplish the obstacle course and then those classmates would help other classmates accomplish their math courses and then those classmates would help [others] accomplish their leadership component. Everybody there is inadequate at something, but you help others succeed by focusing not just on taking care of yourself, but 'let me succeed by helping you succeed'..

There are pieces of that that I think would be very helpful [in a networked world].

Q. You often say, 'Leadership is our version of the Dark Ages' while others say that leadership is the one distinctive capability that all organizations should focus on.

A. Since I first said that my own intellectual understanding has evolved and I have a more nuanced, more mature view. What I really meant in saying that is that we tended to attribute everything we didn't understand to leadership. Now that we have understood so much more, I actually do share the view of leadership as being integral and important. I also think that we still have way too much of the leader as all-knowing hero mythology and that's why I go back to the idea the greatest leaders are... clockbuilders... [those] who want to build something that isn't about them and can transcend them. That is a non-egoistic approach. That kind of leadership is vitally important.

If you ask a simple question: what is the real truth of that leader’s ambition? Is their ambition ultimately about themselves? Or is it about the stuff that’s in the end, not about them? I would hypothesize, if you go into any culture, you could look at [effective] leaders: it’s those who are deeply ambitious for the cause or the company, the values, the quest, not themselves.

Q. You talk about taking an idea to a business, to a company and a movement. To what extent will the ability to create a movement be a defining factor of greatness?

A. [When you talk of] the progression of entrepreneurship, you tend to think of it as an idea. Maybe you will make that idea into a business. At some point, your business has to become a company, and then maybe you want to make it a great company and then an enduring great company. We began to realize that there’s, in some cases, a bigger version of that.

In Good to Great, we talked about the idea of the flywheel and that the way you built something great is you get your 'hedgehog' (Note: This is a concept which says do one thing and do it well) and you build momentum and you build momentum in the flywheel and that flywheel builds cumulative momentum over time. There's a way to accelerate the flywheel. Amazon is a flywheel effect: it's not a single instance; it is a building, cumulative flywheel.

Kim Smith, who ran New Schools Venture Fund, said to me: "Especially in the social sectors, but I bet it's going to start applying to businesses, there are two flywheels. The flywheel of your enterprise or company. [And] the uber flywheel, the flywheel that’s the context." So it's not just the flywheel of building a school or building Teach for America, but you have the uber flywheel of education reform.

Steve Jobs [had] a flywheel of Apple, but he was always interested in the larger flywheel of the impact that technology could have to amplify the creativity of individuals and that notion of connecting people. Think about why Apple [was] so strong and was even able to endure those years when [Jobs] was in the 'wilderness' and not there. On some level it wasn’t just a company. There was a movement behind.

If you read Gordon Moore's articles from the early 1970s where he's talking about Moore's Law he obviously talks about Intel, he talks just as much about the tremendous transformative effect of doubling computing power over 18 to 24 months and what it would lead to in the way that society would work. Being involved in the semiconductor business wasn't just building Intel, it was also building the entire movement of what microelectronics could do to transform the world. So even far back then, there were people who were starting to think that way.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]

[An abridged version of this interview was published concurrently in Mint]