From time to time, we find ourself in a really difficult situation with lots of stress, suffering and unhappiness. Despite our efforts to make things better, the situation becomes chronic and fails to be resolved. Sometimes there is a pattern; we repeatedly find ourselves in a similar circumstance. The advice of well-intentioned friends and colleagues seems reasonable but hard to implement. So does the advice of self-help books and videos that we so avidly read and watch, respectively. It’s like water off a duck’s back. Very little sticks. The suffering continues.

That is because while I may understand things intellectually, my basic mindset, my most fundamental beliefs and assumptions are telling me something else. For instance, let us take the success narrative. Let us say you are not feeling successful right now. Your best friend tells you, ‘Ravi, you are successful. Look at the number of people who care about you and look up to you.’ But if your fundamental measure of success is something very different—let us say it is about wealth, power, achievements and recognition—your friend’s advice is simply meaningless. Unless you are able to change your definition of success, you are not going to feel better about yourself.

The beautiful thing is that you can reprogramme your assumptions and beliefs. And when you do, you change your reality. Motivational speaker Dr Wayne Dyer once said, ‘When you change the way you see things, the things that you see change.’ This is one of the most powerful and empowering ideas ever. Let me share a couple of personal examples in this context.

I was 25 when I became a team manager for the first time. It was in 1988, on the shop floor of a unionized American factory where the work ethic was poor. My team members felt that four hours was a good day’s work. My only managerial role model till then had been my mother, who used to run a large home with a couple of maids and a gardener, among others. Her method of managing them would be to supervise them. This involved walking closely behind each of them, catching them doing something wrong and then criticizing them. I unconsciously ended up emulating her. I would spend all day on the floor watching my team and keeping an eagle eye, nagging and scolding them, and sometimes even chasing them out of the restroom if they were taking too long a break. I just hated my work, and I think they hated me. Something had to give.

Around that time, I read the outstanding, now-forgotten, The Human Side of Enterprise by Douglas McGregor. McGregor proposed two alternative theories we hold about human motivation. Believers in Theory X, such as my mom, held that most people have low ambition, are lazy and avoid responsibility. They, therefore, need continuous supervision, external rewards and consequences. McGregor proposed a better Theory Y, whose fundamental belief is that most people are internally motivated, to say, learn and take responsibility. Work should therefore be designed to allow a high degree of self-control and to be intrinsically satisfying. People need feedback and coaching more than supervision. The shoe dropped. I was clearly following Theory X. Perhaps I should give Theory Y a shot. I did. I began treating them as adults. We agreed on what would be acceptable performance in terms of output, quality and housekeeping. I began to teach them the basics of computer numerical control (CNC) programming. We went to other factories on learning tours. For five of my six operators, the results were excellent; only one of them was irredeemably lazy. When I applied to a business school two years later, the most glowing recommendation I got was from the union leader. Much of my professional success in managing even larger organizations goes back to this moment in 1990, when I finally changed my assumptions about human motivation.

Another, more difficult, shift was trying to be less pessimistic. It was not till I was about 40 that I realized that I was actually a chronic pessimist. I always thought poorly of the pessimists around me, and it came as a shock to realize that I was one myself. I knew I had to change for three reasons. First, optimists generally achieve more and are more successful than pessimists; it is rare to find a successful salesperson or entrepreneur who is a chronic pessimist. And I was determined to be successful. Second, no one likes to be around pessimists and negative people. Finally, optimists are happier people. But awareness is one thing, and change is quite another. Fortunately, my friend Steve Knaebel helped me see that pessimists have three fundamental beliefs; when something ‘bad’ happens, pessimists instinctively jump to three conclusions:

- The worst possible outcome is what will happen.

- It will last forever.

- It is personal. Why is this happening to me?

Optimists, on the other hand, know it is rarely personal; hopefully, it will not be as bad as one might fear, and in any case, this too shall pass. Steve taught me to catch myself, to become aware every time I found myself reacting pessimistically and then, consciously challenge the three assumptions. It took a few years for me to change significantly, but change, I did!

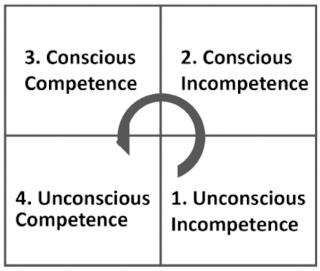

I know from experience that changing your beliefs and assumptions is not easy, but it is always possible. The hardest beliefs to change are naturally the most deep-rooted ones. In my case, they were my beliefs and narratives around success and happiness. In every case, change begins with awareness. Take for instance some aspect of your life that is creating stress or unhappiness and which is simply not getting better. For once, resist the temptation to externalize the cause. Instead, step back and ask yourself—‘How am I unconsciously contributing to this situation?’ Ask yourself what assumptions you may be making about yourself, the other person, about success, about winning and losing. What can you change that might improve the situation? Then test this in practice and take your way forward. As you do this, you find yourself moving from conscious incompetence to a fragile conscious competence before eventually, your new beliefs take root. In psychology, this evolution is known as the conscious competence learning model.

As mentioned earlier: ‘Nothing is as it is. Everything is as we are.’ Once you really understand this, life becomes better and better.

[This excerpt from What the Heck Do I Do with My Life by Ravi Venkatesan has been reproduced with permission from Rupa Publications.]