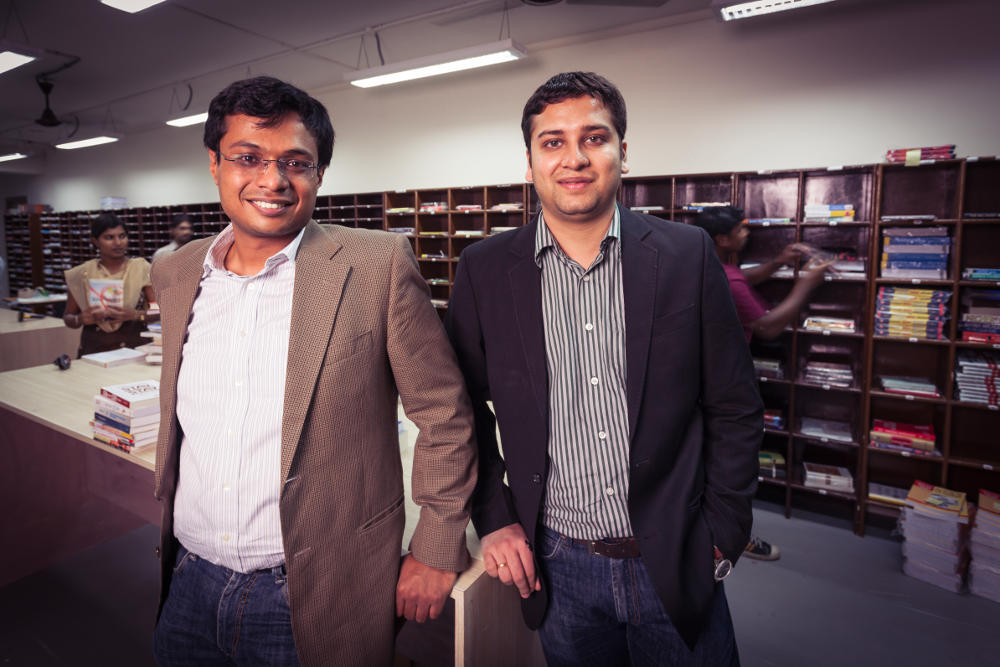

[A file photo of Flipkart co-founders Sachin Bansal (left) and Binny Bansal. The crisis brewing inside will most likely force Flipkart’s investors to look for make-or-break solutions.]

“Picture a girl who took a nosedive from the ugly tree and hit every branch on the way down.” — Private James Ryan in Steven Spielberg's epic movie ‘Saving Private Ryan’

Mark-downs and downrounds (where investors buy a company’s stock at a lower valuation than in previous rounds of funding) punctuate every discussion about Flipkart and the future of Indian e-commerce firms. Too much time is spent discussing Flipkart’s valuation. Is it worth $5 billion or $15 billion?

But everybody is barking up the wrong tree. Flipkart is in the middle of a storm of its own making: It is faced with a significant management churn at the top. For a company that pioneered e-commerce in the country, growth has virtually stalled since the middle of last year and the leadership team hasn’t figured out a way to kick-start sales. Its innovation engine isn’t firing. In e-commerce lingo, the gross merchandise volume (GMV) sold over a given period of time has not grown substantially. In the offline world, it is the equivalent of saying, the sales or revenue numbers aren’t growing. And this, for the e-commerce pioneer that until now grew its GMV by over 200% per annum for the past three years. The very culture that made Flipkart a runaway success in the first phase of its existence is now hindering its progress.

Sure, as things are, Flipkart is the market leader. But Amazon is snipping at its heels and Flipkart has no clue which way to go.

Flipkart is the market leader. But Amazon is snipping at its heels and Flipkart has no clue which way to go.

Eighteen months ago Flipkart was the toast of the Indian internet market and could do no wrong. How did things come to such a pass?

Over half of Flipkart’s GMV comes from selling smartphones—just the Moto series from Motorola is estimated to be worth half a billion dollars. Flipkart focused on just that to the exclusion of everything else. Amazon is now attacking this Achilles heel and is just months away from beating Flipkart to the No 1 position.

The pecking order in our e-commerce market is set to change in the next few months. Permanently.

The ignominy of squandering its first mover advantage to Amazon will only heighten the crisis brewing inside. And it most likely will force Flipkart’s investors to look for make-or-break solutions.

“If your attack is going too well, you may have walked into an ambush.”

— Infantry Journal

A tale of unforced errors

Try this. Borrow another smartphone and open up the Flipkart and Amazon apps simultaneously. Spend a few minutes tinkering with them. You’ll see how Flipkart fumbles. The search is poor and the mobile site and app experiences are non-intuitive. Look at the personalization and recommendations and you will see how users get a sub-optimal experience. Dig deeper for an off-beat item and chances are you won’t find it on Flipkart.

I recently bought a GoPro camera and wasn’t sure which model to buy. The reviews and Q&A by Indian consumers on Amazon were leagues ahead of the ones on Flipkart and the decision where to buy from was obvious. Do this for a household appliance and you’ll see that the difference on selection and information is stark—Amazon surpasses Flipkart by a mile.

I am sure everyone at Flipkart knows that this gap exists but the firm ignored it and was solely focused on pushing deals. Why?

GMV-instilled myopia: Call in a team of sharp youngsters, give them a few hundred million dollars and tell them that GMV is your holy grail. Every other metric is irrelevant. And what do you get? Decisions that drive GMV. Every smartphone transaction is worth 10 times or more than the average e-commerce transaction size. It makes growing GMV easy.

So Flipkart sells smartphones by funding such deep discounts that even neighbourhood mobile shops buy from them as against sourcing them directly from the manufacturer. For example, Flipkart funds a 20% discount beyond the wholesale price in the case of Micromax. Now, if you have a valuation round coming up, sign up a few exclusive smartphone deals, pump in discounts and sell a few million smartphones. And you can claim that you will hit $10 billion faster than anyone else. Incidentally, Flipkart fell short of that number by just $5 billion, as Mint reported in this roundup of missed targets by e-commerce firms.

Fact of the matter is, consumers come in to buy these smartphones for discounted prices and little else. The result of this smartphone-will-give-me-easy-GMV-mania is that—not surprisingly—other categories have suffered as has the product experience.

Missed buses: Then there was the distraction created by its proposed app-only strategy last year—it decided to operate only through its mobile app from September, prompting intense debate within the company. It soon abandoned that plan.

Outsiders will always wonder what prompted the decision to go app-only when neither the company nor the market was ready for it. And having taken such a consumer-unfriendly decision, Flipkart (and Myntra) defended it like a petulant child. Sure, smartphones are the primary browsing devices in India but a significant set of consumers prefers to conclude their transactions on desktops at work or on a mobile browser. Why walk away from them and force them to download an app?

Wonder what prompted the decision to go app-only when neither the company nor the market was ready for it.

Flipkart had a head-start as well in creating the gold-standard on payments with Payzippy. But it pulled the plug on that even as it announced that mobile payments was core to its strategy and invested instead in ngpay in 2014—and nothing has come of it. The company has struggled to create a wallet or even a basic loyalty programme.

The firm took its eyes off the innovation engine. The biggest innovation in the last few years was Ping, a feature where consumers can buy together online. The media lapped it up. Flipkart seriously expected our attention-deficit audience to halt mid-way through a transaction and invite a friend to buy—isn’t this Facebook-like feature 10 years too late? On the other hand a simple feature that invites you to share your purchase on social media was ignored.

Acquisitions yet to pay off? Myntra came with a great team and supplemented an important category for Flipkart. Apparel brings in the highest gross margins in e-commerce and can make a huge impact on overall profitability. However, between the leadership transiting to Flipkart, the controversial app-only decision and an excessive focus on private labels, Myntra now loses money hand-over-fist and has to introspect over what it stands for as it moves away from high fashion to adding towels and bedcovers.

One big challenge Myntra has to grapple with is permanently discounted merchandise. If it doesn’t offer deep discounts, Indian consumers will switch back to offline retailers, which are now on sale for half the year. Add to this the returns, and cancellations that impose a huge penalty on the online apparel business in India.

To find its way back to profitability, Myntra is betting on private labels as prime differentiators and profit drivers. However, private labels require merchandising skills and not marketplace skills. It is yet to demonstrate the positives of owning a clutch of sub-scale private labels (10 at last count). Every online fashion retailer wants use the ASOS playbook (ASOS is considered one of the more successful apparel e-commerce players in the world). But if you look carefully, ASOS has built a monolithic label versus the spray-and-pray private labels at Myntra. It will be interesting to see how it can support as many of them.

The saving grace for Myntra is that Amazon has scaled back its fashion offerings after making some very extravagant moves on the back of sponsoring the India Fashion Week. Jabong is in the doldrums, and awaits a white knight.

Spin off eKart: Sure, Flipkart has built a solid logistics business. Spinning it off appears to be a sound move. eKart can show immediate profitability and overlaying third-party businesses allows it to defray its costs over larger volumes, giving Flipkart even more leverage and room to improve operating margins both at eKart and Flipkart. It also provides a hedge to Flipkart’s investors—value has been ring-fenced into a profitable entity that doesn’t face a threat of assault that may emerge from the Amazon-Alibaba combine.

However, as logistics in India becomes sophisticated, it will involve more capex, automation, technology and resources. So let’s state the next point: spinning off in itself is no guarantee of success. If eKart has to compete in the market and raise resources independently, the moment we have a new set of shareholders and the contract with Flipkart becomes one of arm’s length, one of the businesses will have to suffer margin contraction since eKart’s biggest gain comes from the leverage of Flipkart’s business (synergy). And Flipkart’s shareholders will want the value to be captured by them, either via equity or preferred terms of business. There is massive competition in the space. And if China is any example, it will be many years before the logistics market matures and throws up a few successful players.

Unwieldy size: Imagine you order a battleship and the shipyard delivers you a fancy, large luxury cruise liner—fitted out with heated swimming pools and saunas versus gun turrets, missiles and torpedoes. What war will you fight? That’s what has happened here. Flipkart has built a cruise liner, not an armada of nimble battleships. Over 35,000 people run the ship, adding to overheads that a competitive “take rate” (the commission a marketplace charges on the goods and services sold through its platform) won’t support. The most successful retailers in the world from Walmart to Costco to Amazon are first known for one single virtue—frugality.

What war will you fight? The most successful retailers in the world are first known for one single virtue—frugality.

As one of Amazon’s 14 Leadership Principles states, “We try not to spend money on things that don’t matter to customers. Frugality breeds resourcefulness, self-sufficiency, and invention. There are no extra points for headcount, budget size, or fixed expense.”

This cardinal principle was thrown to the winds at Flipkart and replaced instead with free lunches and trend-setting paternity leave. Successful retailers watch every single penny, every wasteful transaction and every returned product. They are on a constant feverish hunt to cut costs and find efficiencies. This bad behaviour has come back to bite. We all know what happens to fancy cruise liners, don’t we?

“Confusion in battle is what pain is in childbirth—the natural order of things.”

— General Maurice Tugwell

Compounded by a bigger issue—leadership

There are other points where Flipkart has stumbled but let’s attack the elephant in the room. Leadership.

This mega-ship was torn between the agendas of the founders, as this piece in Mint talks about eloquently, and the Silicon Valley hires. The internal conflicts and uneasy tugs of war over decisions led to a point where the company hasn’t shipped out any innovation for the past two years. The team spent time basking in media glory, appearing for events and angel funding than readying themselves for an inevitable assault by Amazon. It was clear that Amazon, having lost China, will adopt a take-no-prisoners approach in an unrestricted Indian market.

Amazon, having lost China, will adopt a take-no-prisoners approach in an unrestricted Indian market.

Meanwhile, at Flipkart, the core team went asunder—over half of the key managers have left and have been replaced by consultants and smart analysts, not veterans of the retail business. There is a reason why Silicon Valley-returned managers (not techies) have a tough time settling in. Granted, they are smart people. But they are used to dealing with homogenized audiences in the West and this is the first time they are coming in contact with the chaos that is India, the diversity that comprises its consumers and the work ethics that create its organizations. That takes some getting used to and time is something Flipkart does not have.

It’s not Flipkart alone: Flipkart’s story is playing out in several other startups, especially e-commerce. Snapdeal is in the same boat and will have to restructure to survive. Both will have to cut thousands of jobs, roll-back their humungous media budgets and restructure their businesses. This will play out against the backdrop of Amazon and the Alibaba-Paytm alliance gearing up for a second assault.

Another company, Inmobi, seems to be in distress and there is an eerie silence on the fate of Miip. Miip claims to be a game-changing innovation in the mobile commerce space. However, the glut of mobile inventory simply leaves too little on the table for intermediaries who have to compete with the intelligence-cum-traffic offerings by Google and Facebook.

Startups that were wasteful now face an existential crisis. They can’t “grow their way out” of the problem anymore, since investors have lost nerve in the face of the reality that unit economics in India in the B2C space may continue to be challenging for many years. Most VCs invested without thinking about India’s unique landscape and I wrote about this in my article The fault in our startups in January. China saw an unprecedented e-commerce boom. But that accompanied an unprecedented boom in the disposable income of Chinese consumers as well. Until that kind of disposable income expansion takes place in India, I don’t see how anyone will be able to turn in a profit and grow at the same time.

Startups that were wasteful now face an existential crisis. They can’t “grow their way out” of the problem anymore

Consumer internet startups find it difficult to navigate slowdowns. Traditional companies usually recover from these cycles. But technology-led companies, they simply go bust. They have very little consumer loyalty to start with. Most bribe consumers to grow rapidly and cutbacks cause them to implode. It becomes a house of cards with dreams of ESOPs disappearing like dew on a hot sunny Indian morning. This has played out in several businesses like fab.com, Homejoy and closer home in Fabfurnish that was sold for cash-in-the-bank (i.e. the value ascribed to the company was zero) after raising $30 million. Veteran Silicon Valley venture capitalist (VC) Bill Gurley wrote about this last week and it is uncanny how it applies to the craziness we have seen in the India market.

Most founders have never faced a crisis of this kind before. They’ve been blissfully building in hopes that transaction volumes and traction will get them their next funding rounds. Profit and loss statements, cash flow, downsizing and re-structuring operations are alien ideas. Even most VCs don’t have teams that have seen acute business cycles like the ones with grey hair like me saw in 1991, 2000-1 and 2008. It’s unchartered territory for the teams that have to suddenly grapple with demands from their VCs to “turnaround” the business metrics.

Another point: The rhetoric seems to have suddenly shifted to “breakeven”. Every startup has announced its intention to become profitable. Breakeven is not the goal for a startup—not at this stage in India. Another 100 million consumers will join the internet economy in the next two years. Stop investing and you could win the battle, but lose the war. In my role as a private equity investor, I end up seeing at least one mid-stage consumer internet deal a month ($100 million plus in GMV) and the founders pitch how they will breakeven. My focus is not on their breakeven, but whether the firm is leveraging the natural advantage the internet and mobile offer to create a wedge in a market and profit from that wedge. Unfortunately, some founders are so focused on GMV and consumer acquisition cost that they spend little time using data analytics, social media, consumer delight, and referrals as the key to creating sustainable unit economics. I have talked about this in my earlier piece, Your startup is dying.

For startups that can demonstrate sustainable metrics, investors will be happy to continue funding the cash burn. The internet boom in India is starting to take off; it is not at the end. Billions of dollars are waiting at our shores—the dry powder with Indian VCs alone is over $2.5 billion. It just needs to see sensible businesses and level-headed teams. The internet clearly is a winner over the older ways of conducting business in India. Question is, are you able to demonstrate and exploit that inherent advantage, or is your business built on an edifice of customer acquisition costs that have no pay-offs?

For startups that can demonstrate sustainable metrics, investors will be happy to continue funding the cash burn.

[The very culture that made Flipkart a runaway success in the first phase of its existence is now hindering its progress. The internal conflicts over decisions have led to a point where the company hasn’t shipped out any innovation for the past two years. Photograph by Hemant Mishra - Mint]

[The very culture that made Flipkart a runaway success in the first phase of its existence is now hindering its progress. The internal conflicts over decisions have led to a point where the company hasn’t shipped out any innovation for the past two years. Photograph by Hemant Mishra - Mint]

Coming back to Flipkart: Let’s get valuation out of the way. A downround is inevitable and an IPO is impossible. Flipkart has to get through rough weather and emerge as a robust, vibrant organisation which is not under continuous siege, internally and externally. So what should Flipkart do?

"You, you, and you … Panic. The rest of you, come with me."

— US Marine Corp Gunnery Sgt.

Back to basics

Take the hit and forget chasing GMV. It’ll be a few media headlines for a few days. So don’t waste money chasing a “vanity” target. Find new metrics. Shrink to become stronger and create deeper and more meaningful experiences for customers. Reduce dependence on smartphone sales. Inspire customers to shop regularly instead of trying to sell phones to a person who goes bargain hunting for a phone once a year—they bleed you.

In times of crisis, lack of clarity and focus on decisions kill organizations faster than the external world can. You need to focus on delivery. Your actions should speak more than the public relations (PR) department. Lock down and huddle with your leaders and get back to basics. Play to your strengths. You have years of experience and knowledge of your consumers.

In times of crisis, lack of clarity and focus on decisions kill organizations faster than the external world can.

Create a command room: Democracy is the worst way to manage in a crisis; but democracy runs in the veins of these new-age startups. The instinct is to call entire teams into a room and throw a problem at them. In a crisis, you have to run counter to these instincts. You need to create an army command centre, a few people, hard decisions, and ruthless execution. You don’t need 100 things to do on a sprawling agenda. You don't need every intern to give you a new idea a day. Engage with the troops and galvanise them around key priorities. The leader now needs to be seen, front and centre with the teams, not with the media.

Democracy is the worst way to manage in a crisis; but democracy runs in the veins of these new-age startups.

Take deep cuts: A slow and lumbering restructuring can drown morale and spread panic. It’s better to craft a plan, take a deep cut at one go and put the rest of the organisation out of agony. Cut away all the extraneous stuff that doesn’t matter to the consumer experience and marketplace. Amazon wrote the playbook for e-commerce 15 years ago—just follow it to a T. Free up those resources. Crisis usually brings clarity since you focus on the essentials to survive. Simplify the organisational structure—and make strong, confident moves.

Overhaul the product: Flipkart was the benchmark for a seamless buying experience until two years ago. It has lost that mojo. The team needs to get it back. It has to think and act like a guerrilla now—nimble, agile and use its knowledge of the landscape to win. Millions of Indians are first-time buyers online. Flipkart needs to capture them earlier in their journey and aim to engage them earlier into the decision process in a uniquely Indian manner. Come in before people start noticing they need to get summer outfits or replace their smartphones or cars. Inspire them to explore and give them the tools to make a decision. Create buying guides in video and regional languages directly or via collaboration with other platforms. Launch new categories that grab consumers’ attention.

Payments: That will stay a bugbear. It’s imperative that Flipkart crafts a payment and loyalty system and find a way to cut down cash on delivery and returns which suck profitability. The cashback strategy of Paytm has been an eye-opener and Flipkart will do well to follow fast.

Reward the loyalists: The 20/80 rule holds true in ecommerce—20% of Flipkart's consumers probably give them over 80% of the business. But there is nothing special for the loyalists. I am a member of Flipkart First but I don’t feel any love—it pales in comparison to the near-instant shipping “Amazon Fulfilled” provides. Amazon is gearing up to launch an Indian version of Amazon Prime (a service that bundles free delivery with unlimited video content for a fixed price and has proved to be a money spinner for Amazon). Flipkart First needs a rethink—and should be the spearhead to launch new categories of products and services and innovate on consumer credit.

Spin the flywheel: Horizontal e-commerce players are not designed to make money off their core business—that of matching buyers and sellers on their marketplace. That means that the marketplace needs to run as a highly-efficient “nil margin” operation and deliver the benefits of scale to its customers. That’s how Amazon and Alibaba do it—it keeps competition out and keeps the moat intact. Money is made off services that they provide to the ecosystem—logistics, payments and advertising. And from continuously finding new ways to adding new categories. I had discussed some of this in my earlier piece, The Mahabharata of Indian internet unicorns. Flipkart has a massive user base and should drive down costs to the barebones. If it becomes the most efficient player in the market, its position can remain intact and it can then use the base of consumers and think like a network. Advertising, new product launches, services, payments, online-offline partnerships are all ways to make money and deepen Flipkart’s moat.

“The purpose of war is not to die for your country. The purpose of war is to ensure that the other guy dies for his country.”

— General George S Patton

Last words

The battle won’t be easy. Amazon will unleash Amazon Prime, Amazon Fresh and may even partner with offline retailers to consolidate its position as the default destination for online shopping. Amazon has rapidly scaled up its seller ecosystem and outstrips Flipkart today in several product categories. It has a chance to win India—and that is being handed over on a platter thanks to the internal confusion at Flipkart. Amazon is here to play a 20 year game—and any fumbles will cost competitors heavily.

Now imagine the Flipkart investors’ dilemma. They’ve poured in over $3 billion and own over 80% of the company. They are neck deep in a business that is burning $50-70 million a month and has to get ready for the next phase of battle in the market. If the cost-cutting moves misfire and market share starts to shrink, the founders could very well put a request for another $500 million for the fight against Amazon. What will the investors do? A new investor is unlikely to step in. Even though the Chinese e-commerce players like Alibaba are waiting in the wings to swoop down on prized assets in India, there's a chance that they could choose to wait out this stage of the company’s evolution—why buy and restructure, when you can wait and buy a cleaned-up asset? Hence, one of the current investors will have to lead the round and it will put serious pressure on the team to show results. It could insist that the company brings in a global e-commerce veteran to guide the business operations and ask the founders to move into roles that are more visionary.

What’s clear is that the firm needs is a bunch of solid, experienced, execution-oriented professionals with years of retailing experience under their belt. People who are sharply focused on execution and cost efficiencies. A lot of value can be squeezed out of the current operations. Folks who build technology companies may not be the best people to run them with ruthless efficiency. It requires a rare mix of rigour and creativity to do that.

Flipkart has a last chance to redeem itself and take control of its destiny, else it will become another victim of early success. It is too big to fail and the market opportunity is too large to ignore. India will have more than one large e-commerce player—just the sheer potential of the market will keep it from consolidating for many years—and so, Flipkart’s existence is not in question. But the next few months will determine the destiny of the company. The A-team cannot afford to flounder so early in their journey.

Editor’s Note:

The data and misinformation on the e-commerce market in India can create a lot of confusion. Haresh Chawla debunks Morgan Stanley's data and forecasts as well as other myths surrounding India's e-commerce market in this follow up piece: "Indian e-commerce: Misled by bad data". He expands on points including conflicting market data, traffic and installs, the metrics that count, why app-only was a costly move, and more.

What do you think Flipkart should be doing to regain its momentum? Share your thoughts with us in the comments section below and engage in a conversation with our contributor Haresh Chawla.

Take a poll on Twitter

Will the funding slowdown separate boys from men in India's #ecommerce market? (Full story: https://t.co/rcf3H9QboB)

— Founding Fuel (@FoundingF) April 24, 2016

Read related articles by Haresh Chawla