[Image by Buffik from Pixabay]

Tushar, an MBA student, didn’t expect a survey related to his second year project work to go this way. His research focused on how 40 to 60-year-olds managed their personal finances. The interviews on Zoom went well. Then came the 17th respondent.

The 47-year-old mid-level executive in a family-run firm got agitated, said his privacy was being violated, and disconnected. For about 30 seconds Tushar stared at himself on the screen, as his heart sank.

Later, when his father, whom I have known for nearly 30 years, recounted the anecdote to me, I remembered my own irritation when businesses ask for information that I considered personal. For example, whenever the staff at the supermarket cash counter demanded my phone number I mostly responded with an, “I am sorry, I don't want to share it” with varying degrees of rudeness.

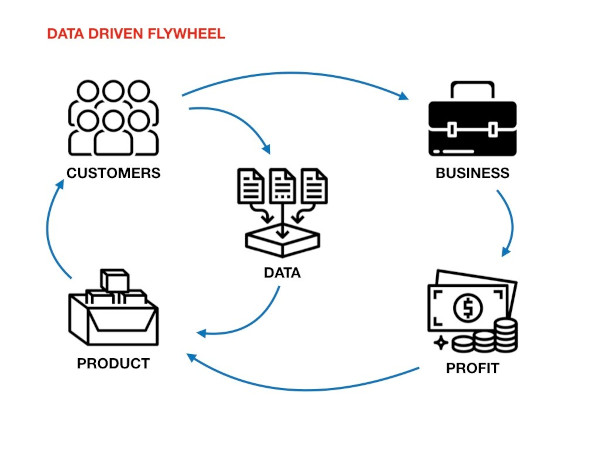

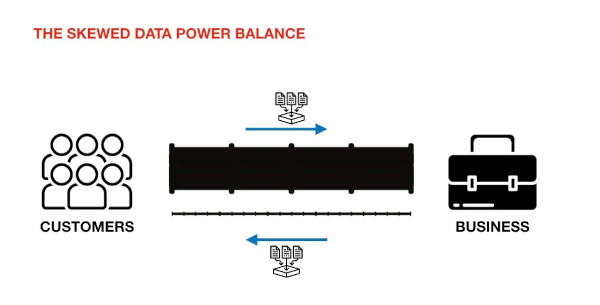

We tend to look at data sharing as a power play that is tilted in favour of businesses and governments. We see it as a violation of our privacy, especially when someone does it face to face (like Tushar or the supermarket billing staff), but we don’t think about it when it’s done digitally (like Google or Facebook do far more deeply and often deviously).

What’s worse, we don’t have access to the data these companies collect about us. With Facebook, it’s hard even to know what it collects. Twitter lets us download data that it believes is “relevant” for us. Fitbit gives us data that tells even less than its dashboard. It’s as if they are driven by a paternal instinct to keep our own data out of our reach.

Most of our commercial transactions tend to be as if they are between adults. But when it comes to data it is like a transaction between a parent and a child, the role of a parent taken by the state and businesses which claim to have our interests in mind.

But, what if it becomes an adult to adult transaction? Above board, done with consent, and we willingly share it in return for some specific benefits.

This key mindshift—data transactions taking place between adults who know the costs and benefits—is at the core of the Account Aggregator (AA) model that went live in India last month.

Adult to adult conversations

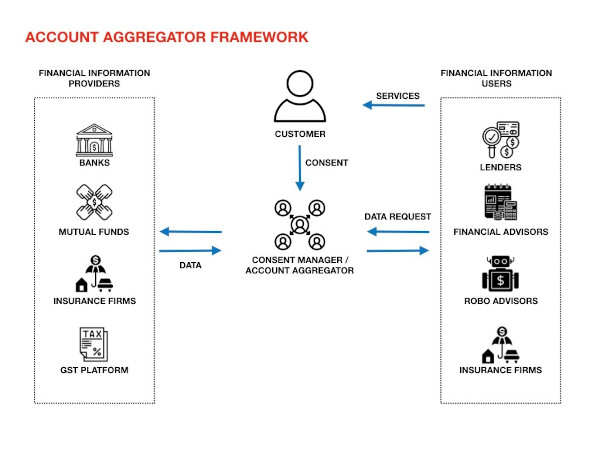

The AA model lets users share financial data—from banks, insurance companies and other entities—with any other regulated organisation that would use the data in return for a benefit, such as home loan or financial advice.

The model includes RBI-regulated Account Aggregators (the user can choose which aggregator they want to go with) that act as an intermediary to securely and digitally share a user’s financial data between regulated entities on the AA network, once the user gives it permission to do so. So far eight entities have joined the network as AAs, four with operating licenses (CAMSFinServ, Cookiejar Technologies, FinSec AA Solutions and NESL Asset Data) and four with in-principle approvals including Perfios and PhonePe.

In some ways, the AA framework builds on the earlier work on Aadhaar, which is a digital identity platform, and India Stack, a group of digital public infrastructure that enables people to authenticate identity, share documents, and make payments. The most popular India Stack offering is UPI, or unified payments interface, on which 3.65 billion transactions took place in September, on apps such as PhonePe and Google Pay.

But, the idea behind the AA framework, of getting a benefit by safely transferring data, goes back even further to eKYC which was launched soon after Aadhaar. When we do an eKYC transaction to open a bank account or get a new telecom connection, what we are essentially doing is giving consent to UIDAI, which has our demographic information, to pass on our data to a bank or a telecom company. It’s the same process when we use DigiLocker to send certified documents—such as a marks sheet or our driving license—from one institution to another.

Transferring money might look very different from transferring data, but even on UPI, we are essentially transferring data. A closer look at how a UPI transaction takes place will throw light on how the AA model works. When you use PhonePe or Google Pay to send money to a friend, there are two other entities besides your app—your bank, which has your money, and your friend’s bank, to which you want to send your money. In the AA framework, we have the financial information provider (FIP, the regulated entity that has your data—one or some of the 17 types of data that this model allows right now) and there is the financial information user (FIU), the equivalent of your friend’s bank. The financial information user could be a lender, or a robo advisor which uses the information you send to provide some benefit to you (such as loan or financial advice).

The term ‘Account Aggregator’ might suggest that an intermediary agency aggregates and stores your data. It doesn’t. The tech is designed so that they have no visibility on your data. What it does is manage your consent to pass on information from FIP to FIU. For the role they play, a better term would be ‘consent managers’. There is an interesting story behind why it’s so named. The engineers behind India Stack have been working on a consent platform right from 2015-2016. Meanwhile RBI was thinking of bringing out a policy to enable sharing of data, and had a working name for it—Account Aggregators. The framework built by the India Stack team turned out to be the right technology for it, but the name stuck.

The long timeframe also meant they had time to build an ecosystem, first through volunteers from iSpirt, a think tank for the Indian software products industry, and then through Sahamati, a non-profit organisation set up for this purpose. The interactions and the feedback helped. The system we have today has more players in the game, and has undergone more iterations than UPI had when it launched. For example, take the grievance redressal system. Pramod Rao, group general counsel for ICICI Bank, pointed out in a column in Bloomberg Quint, that “multi-tier dispute resolution process, which keeps pace with technological advances, and makes available speedy, cost-effective resolution processes (including automated dispute resolution process and online dispute resolution), and fosters the use of APIs to facilitate a smooth transition from one tier to the next or in the choice of online dispute resolution institutions.”

All these have drawn praise from entrepreneurs. Nikhil Kumar, co-founder of Setu, a startup building digital infrastructure for fintech, said the introduction of consent managers places India ahead of the countries trying to put more control in the hands of users. The introduction of the AA framework should also be seen in the context of other developments including the growth of UPI. As Amrish Rau, CEO of Pine Labs, tweeted, “Indian FinTech is buzzing. Govt & RBI are trying many innovations. Keeping up is getting tough. What a time to build!”

A time to build

A key thing about technology platforms, and even more so, technology protocols, is that the innovations that happen on top of them are limited only by the imagination, or the demands of the market.

When Sahamati organised a hackathon earlier this year, one of the interesting use cases that came up—something that probably was never in the minds of people who designed them—is to connect financial information to dating apps, so a user can be certain that the potential partner is not bluffing about their wealth or income. (If this does come to fruition, it need not necessarily share your financial details, but only confirm whether the information you’ve mentioned is true or not.)

It’s likely to evolve in phases. In the first, pain points associated with the present data sharing processes will be ironed out. For example, if you want to take a loan from a bank, you don't need to provide hard copies or PDF documents. Instead you will send the relevant financial details to your lender by taping a few buttons on the Account Aggregator app.

Eventually, the market for new products will open up or expand. For example, right now, the dominant model of lending is asset-based. In flow-based lending, the financial services company looks at your income and expenses, and determines your ability to pay back the loans, and decides to go ahead or not. Capital Float, a Bangalore-based fintech company, follows this approach.

This can be a huge blessing for micro and small businesses that presently struggle to get loans for the lack of credit information.

In parallel, the ease with which one can share information might also bring in financial advisors using human expertise or algorithms to look at your data and provide the right kind of advice.

While AA is limited to financial data, eventually, one can expect to see other types of data being shared with the user’s consent—from telecom, to health and fitness—which in turn could create more service opportunities.

It’s not about technology alone

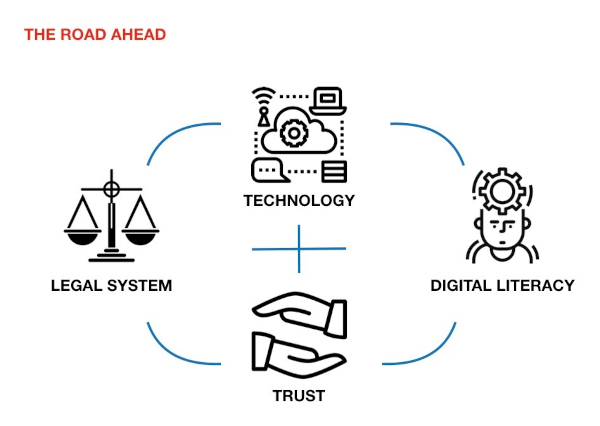

However, when technology meets the real world, there will always be consequences whose intensity we might have underestimated, or completely failed to anticipate. There’s a need for a law and legal institutions to protect user data. Businesses have to work hard to build trust. And most importantly users have to be aware of the digital risks.

Having strong laws would help address some of the harms caused by tech. As Rahul Matthan, a partner at law firm TriLegal, argued in one of his columns, “The fact is that when it comes to regulating technology, you simply cannot have one without the other. Technology businesses are most effectively regulated through a judicious mix of law and technology—strong, principle-based laws to provide the regulatory foundation, with protocol-based technology guardrails to ensure compliance.” India is yet to pass a data protection law, even though a draft law has been around since 2018.

However, even laws won’t suffice. Companies in the ecosystem, both financial information providers and users, have to build trust to make it work. In an HBR essay, Timothy Morey, vice president of innovation strategy at frog, a product strategy and design firm, shares some of the findings of a research they conducted that are relevant to the AA ecosystem. He and his co-authors wrote, “A firm that is considered untrustworthy will find it difficult or impossible to collect certain types of data, regardless of the value offered in exchange. Highly trusted firms, on the other hand, may be able to collect it simply by asking, because customers are satisfied with past benefits received and confident the company will guard their data. In practical terms, this means that if two firms offer the same value in exchange for certain data, the firm with the higher trust will find customers more willing to share. For example, if Amazon and Facebook both wanted to launch a mobile wallet service, Amazon, which received good ratings in our survey, would meet with more customer acceptance than Facebook, which had low ratings. In this equation, trust could be an important competitive differentiator for Amazon.”

But, ultimately, to avoid the harms that might come, it’s important for users to be aware of digital risks (and key for all players in the ecosystem to help build that). Gerd Gigerenzer, director of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy at University of Potsdam, has argued that there have been primarily three ways that we have tried to address the risks—paternalism, nudge and building competence. In the context of AA, techno legal institutions tend to take the paternalistic approach. Inspired by behavioural sciences some businesses might try to nudge people from taking too many risks. But Gigerenzer’s favoured approach is building competence. In a piece in Scientific American, he writes, “risk literacy concerns informed ways of dealing with risk-related areas such as health, money, and modern technologies.” It’s probably the hardest, but also the most effective.