[From Unsplash]

By Subhashis Sinha and Nikunj Kumar Jain

Most organisations that struggle with disability inclusion do not think of themselves as exclusionary. On the contrary, many would describe themselves as progressive, empathetic, even forward-looking. The problem lies elsewhere. It sits in a quieter, less examined space—in how leaders imagine capability, risk, and “fit”.

Consider what happens in a typical hiring or staffing discussion. A candidate with strong credentials is shortlisted. Somewhere in the conversation, an unspoken hesitation enters the room. Will this be “too hard”? Will managers know how to handle it? What if something goes wrong? The questions are rarely voiced openly, but they shape outcomes all the same. The result is not explicit rejection, but cautious sidelining.

Disability inclusion falters not because of hostile intent, but because organisational imagination stops short. What is framed as care often becomes constraint. What is presented as concern quietly limits opportunity.

This is not merely a problem of compliance or infrastructure. It is a leadership problem—one that reveals how Indian organisations still define talent, confidence, and control.

These abstract hesitations have real consequences inside organisations. They shape who gets hired, who gets stretched, and who is quietly protected from opportunity. For many professionals with disabilities, the challenge is not entry alone, but what happens after the door opens.

Consider the experience of Randeep (name changed), a visually impaired IIM graduate employed at a multinational bank. After months of rejections, he finally secured what appeared to be a role aligned with his training in risk analytics and corporate finance. He believed the hardest part was over.

It wasn’t.

Despite his qualifications and internships, Randeep found himself excluded from core analytical assignments. Client interactions were quietly discouraged. Complex modelling work was routinely assigned to others. What remained were routine tasks that bore little resemblance to the role he had been hired for.

“The barrier wasn’t my skillset,” he said. “It was their imagination of what I could or couldn’t handle.”

Randeep’s experience is not an outlier. It points to a broader organisational pattern: even when persons with disabilities enter firms on merit, they are often denied access to challenging work, career pathways, and professional trust.

When such patterns repeat across organisations, they show up in aggregate outcomes.

An examination of the top Sensex-listed companies as of March 2024 reveals a persistent and systemic gap. Across private-sector firms, the share of employees with disabilities remains vanishingly small. Public-sector organisations perform somewhat better, but still fall well short of statutory intent.

This consistency matters. It suggests that the issue cannot be explained away by patchy reporting or isolated lapses. The problem is structural. Organisations are not hiring persons with disabilities at scale—and when they do, they often struggle to integrate them meaningfully.

The legislative architecture is not the binding constraint. India ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2007 and enacted the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act in 2016. The Act articulates a clear objective: dignity, non-discrimination, and equal opportunity. It also establishes expectations—particularly for public-sector employment—and encourages private employers, through incentives, to move in the same direction.

Yet inside companies, disability inclusion continues to be interpreted narrowly, largely through the lens of compliance and infrastructure. Ramps are built. Accessibility audits are conducted. Annual disclosures are filed.

But inclusion is not a function of infrastructure alone.

A telling detail appears in one company’s annual report, which describes its disability workforce as comprising “hearing, visual, locomotor, orthopaedic and others.” The law recognises more than twenty categories of disability. “Others” is not one of them.

This is not a semantic slip. It reflects a deeper unease. Disability inclusion is treated as an obligation to be managed, not as a dimension of talent to be developed.

HR leaders admit this, often candidly and in private. A senior HR leader in a financial services firm described their organisation as “very raw” in its understanding of the RPwD Act. “We are trying to build awareness,” he said, “but we have a mountain to climb.”

Another leader heading diversity and inclusion at a large manufacturing firm put it more bluntly. Disability inclusion, he argued, is still approached as compliance, not as a source of competitive advantage. Leadership conversations fixate on infrastructure and visible disabilities, because those are easier to grasp. Many other disabilities, he noted, require far less physical adaptation and far more managerial confidence.

The common thread running through these accounts is not lack of intent. It is lack of confidence—on the part of leaders and managers—to imagine capability differently, to assign responsibility without overprotection, and to accept a degree of uncertainty.

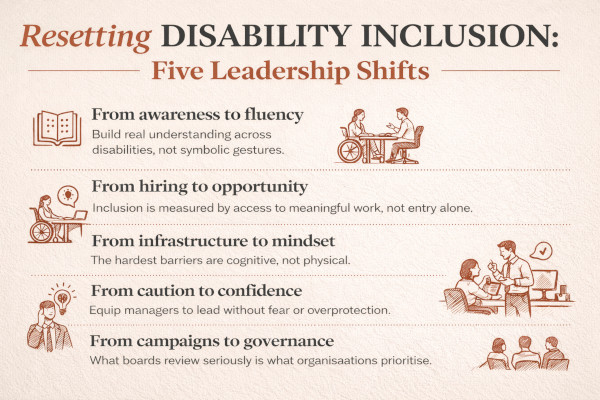

What this ultimately calls for is not a checklist, but a set of leadership shifts in how disability inclusion is understood and practiced.

Unless disability inclusion is treated as a strategic capability rather than a compliance ritual, it will continue to stall—well-intentioned, well-publicised, and quietly ineffective. For Indian companies grappling with talent constraints and leadership credibility, this is a missed opportunity hiding in plain sight.