(All photo courtesy Bangalore Lit Fest)

Editor’s Note: Organisers of cultural festivals — be it for literature, art, music, dance or films — face a set of existential dilemmas. How do they make their efforts sustainable and independent? Is it time to look beyond corporate sponsorship for more creative options? Till then, the task of preserving our cultural heritage hangs in the balance.

Join our special Ask Me Anything (AMA) chat with V Ravichandar, organiser of the Bangalore LitFest, and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, the director of MAMI and founder of the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) on Friday, December 20 from 6:30 PM to 7:30 PM. Register: https://lu.ma/ribi5smz

Cultural institutions like literature, film, and music festivals around the world are increasingly facing a dual challenge: securing funding while maintaining their independence and inclusivity. This tension is particularly evident in India, where the cultural landscape is both vibrant and diverse, yet funding mechanisms, even in big cities, are increasingly strained.

Many festivals rely on corporate sponsorships. Big businesses are ready to fund these cultural events because it helps how the public perceives them — as a patron of arts and culture. But, even the most popular cultural festivals don’t have the mass appeal of an IPL. Businesses prefer to focus on that.

Besides, art and literature festivals sometimes provoke outrage and protests. Jaipur LitFest had to cancel Salman Rushdie’s speech in 2012. The International Film Festival of India (IFFI) in Goa was embroiled in controversy when Nadav Lapid, jury chief at the festival, criticised the inclusion of The Kashmir Files at the event. This is not limited to India. Earlier this year, the Hay Festival in London had to drop its main sponsor after speakers threatened to boycott over the Palestine issue.

Corporates are constantly worried about how they are perceived. In this age of public outrage, guilt by association can impact their businesses. Many prefer to stay out of controversies, and stick to safe events like sports.

We don’t know how these factors weighed in on individual decisions. But, the results are clear. After 15 years, the Tata group pulled out from its anchor sponsorship of the Mumbai LitFest (then called the Tata Lit Live). Fortunately, the Godrej Group and Kotak Mahindra Bank filled that void. The Mumbai Film Festival organised by the Mumbai Academy of Moving Image (MAMI) organised its 2024 edition without a presenting sponsor, after Reliance Jio decided to withdraw its sponsorship. Next year, MAMI will need to find a sponsor and also retain its vigour.

Similarly, the Mumbai Press Club recently cancelled this year’s prestigious Red Ink Awards because it couldn’t find an anchor corporate sponsor, despite multiple attempts.

Bangalore Literature Festival, whose 13th edition starts today (14th December 2024), has figured out some of the answers in the 12 years it has been around. It has consciously avoided corporate sponsorship, and is now the largest community-driven literature festival in the country. Increasingly, it has been trying to reflect the diversity of the city, giving a platform to diverse voices. It has not been able to avoid controversies (and that’s impossible in the world of art and literature), but it has evolved in such a way that it wouldn’t matter.

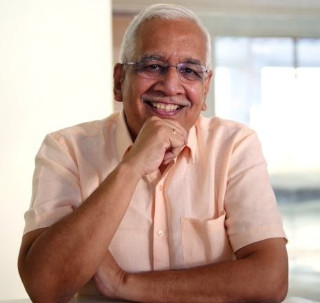

V Ravichandar, a core member of the team, tells its story.

♦¤♦¤♦¤♦

How Bangalore literature festival discovered money and freedom

By V. Ravichandar

(V. Ravichandar is chairman, Feedback Consulting. He is Honorary Consul, Republic of Slovenia for Bengaluru. He is also part of multiple social and cultural initiatives including Bangalore International Centre, Bangalore Literature Festival, and Takshashila Institution.)

The first Bangalore Literature Festival in 2012 had a budget of around Rs 35-40 lakh. We thought we'd go the traditional route and get a sponsor. A large business came forward, and promised to give us Rs 30 lakh. We thought the festival was more or less covered.

But then, with just 10 days to go, they decided to divert their funds to a Mysore Dasara (Dussehra) event. They were uncertain about whether we could pull it off. Suddenly, we had no money for a festival we had already committed to. On the spur of the moment — and I'd almost call it serendipity — I decided to try raising money from individuals rather than relying on corporate sponsorship. With no time left, I couldn't secure another corporate sponsor. I was reasonably confident I could find 30 individuals willing to contribute a lakh each. That’s how the idea of "Friends of BLF" was born. It wasn't some grand, meticulously planned strategy, but rather a solution born out of pure circumstance.

Friends of BLF

The idea worked. In the first year, we had 20-odd people contributing to 30-odd lakh. Some gave a little more than a lakh, most gave a lakh, and we were on our way.

We realised this approach had potential. So, in the next two to three years, we consciously decided to expand our strategy. Each year, we would try to increase our pool of supporters by five to ten people. Today, we have close to 140 Friends of BLF. Every year, we deliberately look out for more people who believe in our cause.

Being a ‘brandless’ festival helps. The whole idea of getting the community to run the festival — without any corporate brands — became our unique selling proposition.

We started seeing its other advantages. With the cancel culture creeping in from various directions, it is better to run a festival with complete independence — where nobody could pull the plug, so to speak. As a result, we made a decisive move: no single individual would exceed 3% of the overall funding. For example, this year our funding is around Rs 2.5 crore, and the largest individual contribution is about Rs 5 lakh, which is technically less than 2% of our festival costs.

The beauty of this approach is that nobody can claim to control the festival. Sure, people get outraged and ask, "Why did you call this person?" or "Why did you call that person?" That happens every year. But we're not dependent on any single entity. No one person owns the festival. In that sense, we de-risk it from the potential of a large sponsor suddenly pulling out.

Now, other cities are interested in this model. Mumbai wants to go our way.

College festival on steroids

The other key thing about the Bangalore Lit Fest that's quite different from most other cities is the incredible volunteer energy that drives it. I always think of our festival as a "college festival on steroids". It's essentially a college-level festival but on a much larger scale. Everybody who works for the festival is a volunteer. Our core team doesn't get paid. The only payments are for practical necessities like flight tickets, hotel accommodations, event management, and social media support.

In the beginning, our core team was about four people. Now we're three — Srikrishna Ramamoorthy, Shinie Antony, and me, the core team that lives and breathes the festival throughout the year. We have what I'd call an "outer core" of another three or four people, like Lakshmi Subodh and Subodh Sankar from Atta Galatta and Shrabonti Bagchi from Mint. They assist with scheduling, titling, and those kinds of details.

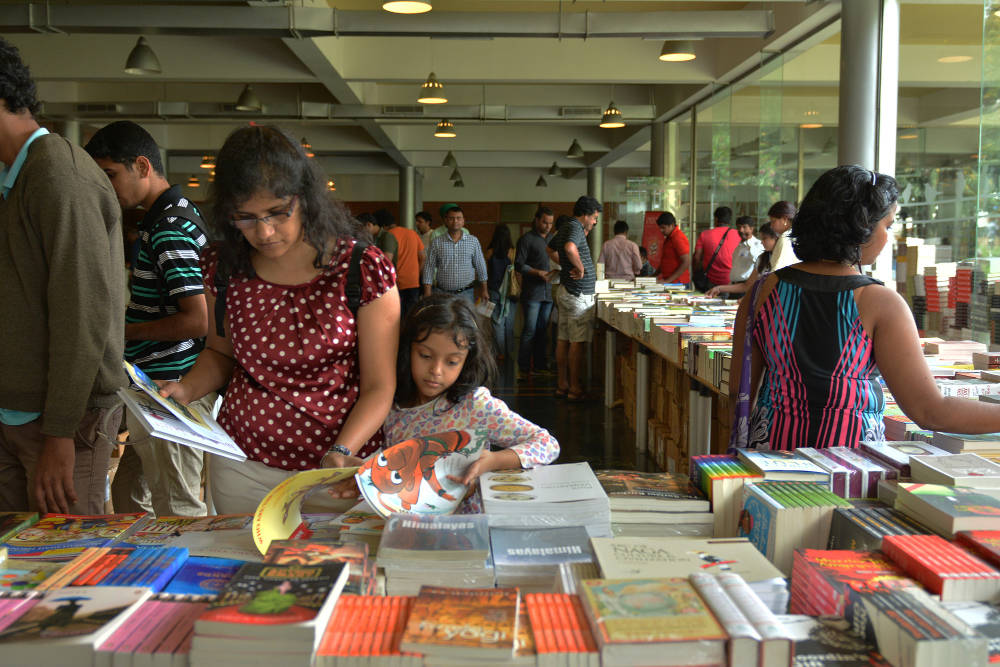

(Bangalore Lit Fest 2018)

For volunteers, we put out an open call and invite them to be part of the festival. We typically have about 25 volunteers helping out during the festival. We used to recruit from colleges, but we realised that model didn't work well. Students would come more for a certificate or to hang out with friends, and the actual volunteering would suffer. Now we have a new approach: we put out an open call, set a specific date for a physical meeting, and only work with those who actually show up. In the social media age, it's easy to show interest online, but the real commitment is in showing up. About 150 people usually show interest because the Bangalore Literature Festival has, in a certain sense, "arrived". From that pool, around 30-40 actually turn up, and we work with those dedicated individuals. They don’t get paid, but we provide daily allowances to cover their travel, lunch, and other expenses.

Subodh runs the bookshop at the festival and plays a significant role in planning sessions. In the early days, he helped a lot with programming. Now Prateeti (Punja Ballal) handles more of that programming work.

We're technically the largest community-funded festival in the country. JLF and others are primarily corporate-funded. While our budget is around Rs 2.5 crore a year, JLF is closer to Rs 25 crore. Scale-wise, they're in a different league. But our model gives us tremendous creative freedom, and we avoid the complications that come with large corporate sponsorships.

The language question

The core team inherently likes to balance multiple viewpoints. While we might be liberal at heart, we're what I'd call "classic liberals" — open to diverse perspectives and going out of our way to ensure inclusion and diversity.

One aspect of that is regional languages, not just Kannada. Last year, we had Tamil and Malayalam. This year, we've expanded it to Hindi, Urdu, and Assamese. There's still a strong Kannada presence, of course, but we've significantly broadened our linguistic landscape. Our Bhasha sessions — which include Kannada and other regional languages — now constitute about 20-25% of the festival.

(Perumal Murugan, a Tamil writer, at Bangalore Lit Fest 2023)

This approach reflects our core philosophy: while we're a national and international festival that attracts overseas and national authors, we're also deeply rooted in the local context. The Kannada programming within our Bhasha sessions remains the most prominent in terms of numbers and volume. It's a delicate balance — being expansive yet local, national yet regional, diverse yet focused. That's the essence of our festival.

We face a complex challenge with these multilingual sessions. Authors get disappointed if large crowds don't attend their talks. It's a double challenge — not just programming the sessions, but ensuring we have an engaged audience. We're committed to making it work, balancing inclusivity with practical considerations.

Crossover audience

We faced a similar challenge at Bangalore International Centre. Now we do at least five Kannada events a month. Over time, BIC has become a hub for Kannada programming, but in the initial days, it was incredibly difficult to attract an audience. Our audience was attuned to English — rightly or wrongly. It takes time to develop a reputation as a place with quality Kannada programming that's worth attending.

The trick is to appeal to a crossover audience. We look for Kannada authors who also write in English, or whose work has been translated into English. This approach helps us slowly assimilate a broader audience into our programming.

If you look at our Kannada list this year, it's not just classical literature. We've got contemporary pieces, a session on young Kannada writers. But what we've really tried to do is use these Kannada sessions for social commentary and slice-of-life narratives. We've included people from All India Radio, Kannada cinema, activists, and voices from Kannada society. While we have well-known intellectuals and authors like HS Shivaprakash, we've deliberately tried to make the programming more generally interesting.

This wasn't driven by audience demand. It was a conscious choice based on a couple of core principles. First, diversity of voices — ensuring we represent different perspectives, from right-wing to left-wing viewpoints. We didn't want to become a homogeneous festival.

The second principle was inclusivity. This manifested in two ways: linguistic diversity, which meant bringing in multiple languages, and representation of progressive issues. We wanted to ensure marginalized voices were represented — LGBTQ, transgender communities, and other underrepresented groups.

Rahul Dravid factor

There's nothing more important for a literature festival than getting people to overcome their inertia and come out. So we do two or three things to make that happen. It's a kind of clickbait marketing.

(Rahul Dravid at Bangalore Lit Fest 2017)

One approach is to have an opening speaker with general appeal. One year we had Rahul Dravid, for instance. We try to invite someone who will attract people, and they'll come for that specific person. Having travelled to the venue, they might think, "It'll take me an hour to go somewhere else, so let me hang around here for another hour or two and see what else is on offer." They might come for one speaker, but then stay to explore what else is happening. And suddenly they find something that interests them, and then they become regulars every year. One of our goals was really about creating new audiences. So we bring in recognizable names.

The second thing we did to increase attendance was to focus on families. Many of us have forgotten — especially the older generation — the challenges of parenting children around eight or ten years old.

Out of our eight stages, three are dedicated to children. Our philosophy is that if you program enough for children, it becomes a family day out. There's something for children, something for parents. In many festivals, children's programming is non-existent. This approach has helped us a lot because people come with their kids. The children are engaged in sessions that interest them, parents can attend their preferred events, and overall, you get a sense of a larger community at the Lit Fest.

What makes a Bangalorean?

We've maintained an inclusive angle from the beginning. We decided to make the festival free and to remain behind the scenes. You'll never see us organisers hogging the limelight or going on stage. Many people don't even know who made this possible — even the authors who have come and gone. During correspondence, they might have emailed Shinie or Srikrishna or me, but we remain nameless and faceless. We welcome everyone like just another volunteer and don't introduce ourselves as festival runners.

The whole spirit is about community.

If you look at Bangalore culture, language is a big marker of identity. But it’s not language alone. So, what defines a citizen of this city? What makes a Bangalorean? To me, the Bangalore Literary Festival and community funding fundamentally answer this question. In a larger sense, the Bangalore community is one that comes forward to support causes that are non-transactional and bigger than themselves. I always call this "privately enabled public purpose" — where the purpose is public, but it's realised through private initiative.

This is how I view the Lit Fest and Bangalore itself.

(As told to NS Ramnath)

Editor’s Note: Organisers of cultural festivals — be it for literature, art, music, dance or films — face a set of existential dilemmas. How do they make their efforts sustainable and independent? Is it time to look beyond corporate sponsorship for more creative options? Till then, the task of preserving our cultural heritage hangs in the balance.

Join our special Ask Me Anything (AMA) chat with V Ravichandar, organiser of the Bangalore LitFest, and Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, the director of MAMI and founder of the Film Heritage Foundation (FHF) on Friday, December 20 from 6:30 PM to 7:30 PM. Register: https://lu.ma/ribi5smz