[Image:Supernova remnants by NASA/CXC/U.Texas. A supernova, or the violent death of a star, happens in one of two ways: when a massive star runs out of fresh nuclear fuel and collapses on itself, or when matter piles up on an already dead star, making it unstable. Will Indian internet startups—flush with funding— go the same way? After all, rapid unadulterated growth can hide several sins in a business.]

[More on This: This article was updated on January 17, 2016, to include a table on hyperlocal delivery startups in 2015, showing cash burn per day; and examples of startups that seem to be going down the right path.]

Just a few days ago, the front pages of newspapers were full of stories reporting that Grofers shut down operations in nine cities. I’m not speaking here with the benefit of hindsight. But it was meant to happen.

To get to what I’m trying to say, visualize the math on a transaction I am just about to describe. A friend spotted an employee from Grofers at a neighbourhood store. For those who came in late, this is a phone-based app that allows you to order pretty much anything and it gets delivered to your place. The intent is to save time you would otherwise spend shopping.

Anyway, to get back to the point, this bloke wearing a T-shirt that indicated he is from Grofers, picked up a half litre bottle of Pepsi and a Cadbury Dairy Milk chocolate.

My friend was intrigued and asked him if this is all he intended to deliver. The boy said yes.

“Kaisa chalega yeh?” (How will this work?) my friend asked. His enquiry was directed to finding out how will it make any money.

“Sir, aise hi chalta hai.” (This is how it is) the boy replied and rushed to complete the delivery.

I don’t have a clue if the customer paid delivery charges on this order or if it was free. But think about the expenses Grofers may have incurred on acquiring this customer, the time spent on procuring the order, monitoring, delivery, accounting and remitting the money if it was a cash-on-delivery transaction.

Even if Grofers did charge Rs 49 for delivery (which I doubt they did), the transaction would have cost more than what the actual goods did. Sometimes, these transactions actually turn out to be free (as in the case of Foodpanda) for customers by applying cashback and first-time use coupons.

Sure, as a tool to drive adoption, these losses are fine. But how many of these one Pepsi + one chocolate customers are sustainable customers? Nobody cares, dammit! That’s what it all boils down to. Which is why I thought it only appropriate I write a note to start ups on where the fault in them lies.

Dear Startup,

Nobody, and I mean nobody has a problem if you die. That is what is meant to be.

Ninety-seven percent of you will fail. About one percent will get acquired. Another one percent will go on to become paper unicorns. That is until the paper burns up as you run through several million dollars before you go down. (For the uninitiated, a unicorn is a startup with valuation upwards of $1 billion.)

Only the final percent of you will actually become sustainable digital-first enterprises. And that too, only until you are challenged and replaced by virtual-reality-cum-anticipation-sensing robots that order things and experiences before I need them.

But let’s come back to you. My problem is that you will die for the wrong reasons.

You will not die because your product sucked. Or your team fell apart. Or your competitor got funded beyond what is rational.

You will die because you were supposed to. Your math never added up. You could never have made money, no matter how hard you tried.

There is no learning. There is no nobility or glory in failure of that kind because you would’ve learnt nothing. Except that all the funding in the world can’t help you if your costs to revenue equation is in the negative.

The only one who would have learnt something is your venture capitalist (VC)—the one who made that bet. He learnt not to bet against Indian consumers. Not to bet against that little calculator in their heads.

Why it is inevitable

In the aftermath of the several dramas, hostage-taking, lay-offs and downsizing of Indian startups, I thought it is time to reflect.

We saw pain in food tech, hyperlocal e-commerce companies, and insta-groceries. We’ve seen deaths in e-commerce, online travel, on-demand cabs and private labels (“strategic-M&A” is still death by another name). Payments will be next. Do I really need 20 electronic wallets besides the little worn out leather one in my pocket? Name the space and there will be blood: education, mobile and video content, couponing…the list goes on.

Mind you, I am not being pessimistic—every startup that dies manages to etch a new neural path in a consumer’s mind as it tries to change an old “analog” habit.

In that sense, startup deaths are noble. They pave the way for another one to come along some day and actually make money off that behaviour-shift that the dead ones lost the battle in trying to create. It’s not really bad for the founders—the resilient ones learn their lessons, pick up the pieces of their lives and start work on their next venture. The principles of Darwinian evolution send the rest of the founders back into nice corporate jobs, and the circle of life goes on.

I am being realistic about it. Rapid, unadulterated growth can hide several sins in a business, and that’s what happened in these firms. I’ve run across founders who did not know how much they were burning, how much cash was remaining, how their unit economics worked. The firms were held aloft by the constant pouring of fuel by the investors.

Unfortunately, all that fuel could not help these firms attain escape velocity. Their rockets were weighed down by huge overheads, bad design and piloted by inexperienced-but-overconfident astronauts.

And then gravity made a giant sucking sound.

“Wherever the hurry to build a billion dollar valuation overtook logic, there shall be pain”

I recently wrote a piece "Your Start-up Is Dying" about the waste in how startups were acquiring customers and then not focusing enough on their experience and retention.

But I realised that there are bigger errors that we are making in blindly copying models from the West. So this piece, in a sense, is a prequel.

Let’s begin with the fatal flaw in our clones.

VCs and founders find it easy to launch clones of Western models because they perceive lower risk in future funding rounds, possibilities of a strategic sale and a general comfort around financing such a business model. They have readymade examples from the West of unicorns, or mega-funding rounds. Clearly, there is comfort that even if things don’t pan out too well, they will be able to sell the startup to a Western or Chinese strategic investor.

They are not wrong. The potential is intoxicating. You see millions of smartphone-addicted Indians, a ready audience for your established-in-the-USA business model, and you want to press the launch button. Success seems to be only a matter of time, not of chance.

Even the clones are cloned—you see the launch of a multitude of clones—as if there is some security in numbers, as if they are fighting a joint battle against evil forces.

But those who forgot that the clone war is being fought on Indian soil pay the price.

We have a devastating problem that blows out the projections of every startup, and puts us many years behind the Chinese internet economy we love to compare ourselves with. Here goes:

Clone Flaw #1: We spend in dollars and earn in rupees

You buy your Macs and pay for your hosting cost and your fuel in dollars. You pay your rent and talent in near-dollar terms. But your discerning Indian consumers count every paisa and leave only rupees on the table.

India is one of the most expensive places in the world for a startup. Even at seed stage most startups need between $200-300,000 to kick off and another $2-5 million to prove that they have a business model that works (or doesn’t, as the case may be). Silicon Valley startups launch with as little as $20,000 and there are genuine incubator networks that propel them along. Salaries and rents are not cheap in India.

To put that in perspective, let’s look at local services startups in the US. A plumbing job on average costs $200 and if you make 15 percent on it, you’ll make $30. In India, the same job costs about Rs 300 and that’ll get you Rs 45. Even on a purchasing parity basis, the US plumbing job makes you Rs 600 a job, a far cry from the Rs 45 in India.

How many thousands of plumbing jobs per day do you need to earn back the imputed salaries of founders who studied at the IITs? (Of course, they are paid via equity. But someone needs to do a rational analysis whether a venture can afford them.) Or the actual salary of a lead software engineer? Or the rentals for your offices? Can such a startup actually afford an office at all?

Indians spend little and that too carefully. That simple fact makes most startups unviable.

Clone Flaw #2: Our absolute unit economics suck

Your percentage gross margin or contribution margin may look promising, but on an absolute level it earns you very little.

Here are the numbers for a reasonably sized vertical e-commerce company (sales of over Rs 1 crore a day). It has a gross margin of over 24 percent and is one of the few that make a positive contribution margin. Not bad given the haemorrhaging one sees elsewhere.

Looking underneath the numbers, it has an average transaction revenue of Rs 900. The contribution after discounts, returns, logistics, but before customer acquisition cost (CAC) was 5 percent or Rs 45 per transaction. Accounting for CAC, the company ends up losing over Rs 100 per transaction on a marginal basis. Over and above that you have to account for crores in fixed costs for team, rentals and other infrastructure.

It’s a coincidence that both examples above earn Rs 45 a pop. You can come to different conclusions on the chances of survival of these startups.

In the case of local services, when will you ever make enough money to pay off your costs since it’s unlikely Indians will start paying more for plumbing jobs anytime soon? We’ll soon see pivots in this space and, more importantly, a focus on owning the customer, versus owning the plumbers. Survival here will become not about the plumbers on your network, but about figuring out how you can inspire customers to use you on multiple occasions. This is a frequency problem. Your low frequency customers can kill you.

Question is, will you be able to drive high-frequency behaviour?

In the second case, the startup will never make money without a clear and clever plan to upsell and drive the average transaction value to 2x the present number. It has an amplitude problem. Your low value customers will dry you up. The next question then is, how soon can you get the transaction value up? Of course, you can solve this by finding ways to upsell, cross-sell or by motivating higher frequency purchasing but that comes with increasing complexity and costs. It needs to find a sweet spot between acquisition and retention efforts.

In both cases, the firms are living dangerously. With such a thin contribution margin, any expense on growth, any headcount they add, builds up huge pressure to do even more transactions, which in turn leads to more overheads to tackle the resultant complexity—and the founders and investors get into what I call the treadmill problem. But more on that later.

Simply put, with such low “absolute” unit economics, each product developer you add is creating pressure to do thousands of more transactions per annum just to cover her wages.

Clone Flaw #3: Depth, density and the Indian mindset

The battle with unit economics is easily won with a small conjuring trick:

Click that trackpad on your Mac and pull the cursor all the way to the right in an Excel sheet. And voila! The model works. At scale, in a few years, and with a few optimistic assumptions, it all works. Quick! Give us that $30 million Series C funding or we’ll go to another investor.

Startups assume that scale will solve their unit economics issues. But wait. You are dealing with a complex, fragmented audience. The depth and density of the Indian market is a fraction of the West or even of China. (China’s internet market is worth trillions of dollars and by several estimates, India will take seven-eight years to reach where China is today.)

There are two Indias: the top 10% that can afford your clone offering, and the remaining 90% that can’t or simply won’t.

Discovery, conversion, retention are expensive propositions in India. If your business does not have natural network effects or massive economies of scale, you could be in a tough spot.

The Indian consumer is value-driven, not convenience-driven. We have all the time in the world to research and find the best price. Most have time to find a competing offer. We hate paying for service. And loyalty—what is that?

Indians will not pay for delivery, service or extra conveniences and will accept deals from your competitors with both hands. Does your clone-model account for this?

Servicing the 90% can become a continuous drain on your business. There is no farming with them, only hunting.

Most founders don’t see that maintaining their existing base will be a cost that will bleed them. Your “light” customers become a load on your business. You can horribly miscalculate the cost of changing the customer’s behaviour. And once you have spent money acquiring them... I have seen startups routinely fail to calculate the cost of customer retention, with deadly consequences.

If you think Grofers was silly, allow me to offer another example: I recently met a firm that showed me how they planned to earn Rs 400 off every transaction worth Rs 2,000. The economics looked good until I delved deeper. They planned to pay Facebook Rs 700 to acquire every customer and they had no plan on how to retain the customer. There was an airy assumption that they’ll get 25% retention—with no basis in customer behaviour, competitive intensity, nothing. It was as if they were working hard to raise money from investors to give to Facebook.

Google and Facebook absolutely love this. Indian startups are like giant funnels of VC money. They see gullible startup founders channelling marketing money from their investors. They have this wonderful hypnotic tool called “remarketing” and startups are lured into spending on the same consumers again and again, while they laugh their way to the bank.

They say, “Here’s an easy way to lure back customers who have visited you but you failed to excite; we’ll bring them back to your website or app; and you can hope this time they’ll transact.”

Most startups spend that money again, without changing anything about themselves, without making any change in the customer’s journey. It’s laziness-on-demand driven by a cheaper cost-per-click offered on remarketing.

Of course, remarketing is a great tool, but it’s just lazy marketing if you keep putting money in it without rethinking the fundamentals of why you need so much of it. It looks cheaper, but you are burning a hole in your own pocket. Think about it. If your business is not generating any buzz or momentum on its own, and is inherently not sticky, remarketing is not the solution. It will not help you jump orbit.

Clone Flaw #4: You compete with a man without a calculator

You are competing with a kirana shop owner, a restaurant owner, a beautician with her own Facebook following. These people know the business, they know their customers, they have the relationships. They can do their own delivery. But we are building startups that want to solve a problem that probably doesn’t need solving.

The point is that you are fighting a competitor who doesn’t measure his own efforts and costs. These cost structures have never been examined under the harsh light of unit economics. Most of them don’t pay taxes, nor do they have regulatory/compliance costs. The typical kirana shop has a delivery boy who will arrange shelves in the morning, deliver during the day, and act as a watchman by sleeping at the shop at night. The marginal cost of home delivery to the kirana owner is near zero.

Let’s consider food tech. Just examine what happens at lunch time—all consumers want the delivery of a sub-Rs 200 order in a two-hour window between noon and 2 pm. Imagine the peak/off-peak demand curve it creates for delivery boys. It’s sustainable only if you can drive density—each boy delivers 5-10 boxes in each office. Unless you are vertically integrated (run your own kitchen and enjoy the 70% gross margins of the food business) you have no hope of making money versus the neighbourhood restaurant which has a delivery boy who cuts onions in the morning, sets the tables before lunch and knows the delivery beat dead-on.

Think hard about the segment you operate in. It’s very nice to draw pie charts and show that you have an addressable market worth billions. But think through who you compete with and what is his cost of doing business. Of course, your scale, assortment and efficiencies will drive these kirana shops and restaurants out of business someday. But when and at what cost? You can’t be paying taxes and bearing compliance costs and expect to win soon.

Clone Flaw #5: The treadmill problem

The lack of depth and density combined with multiple clones fighting the same battle creates another issue. VCs are under pressure to get the bridegroom dressed up for the next swayamvar (an ancient Indian ritual where a bride walks through a list of suitors to choose a husband by garlanding him)—let’s open in 10 cities in next six months, or let’s get 10,000 transactions a day—so that we can attract the Series C from a bulge bracket VC.

In the desire to create the most eligible clone, startups end up wantonly spending on customer acquisition. Resources are spread thin. The cost structure balloons and a few months into this, you discover you are not the rocket you thought you were, but are running on a treadmill—running faster and faster, expending more and more energy, but going nowhere.

Here is an illustrative Excel sheet for an online grocery startup (it eventually shut down).

| All Numbers in Rupees | |||

| Deliveries / Day | 500 | 1000 | 2000 |

| Basket Size | 1000 | 1400 | 1500 |

| Gross Margin % | 17% | 19% | 22% |

| Gross Margin | 170 | 266 | 330 |

| Warehousing Cost | 25 | 25 | 20 |

| Delivery Van | 102 | 84 | 68 |

| Delivery Van % | 10.2% | 6% | 4.5% |

| Manpower Cost / Delivery | 145 | 125 | 110 |

| Manpower % | 14.5% | 8.9% | 7.3% |

| Other Expenses | 10 | 14 | 14 |

| Contribution / Delivery | -112 | 18 | 118 |

The story was that we’ll build efficiency and start making money once we do over 2,000 deliveries a day. But folks, you are in India, you are in a tough market, in a tough business. As you scale, the points of failure go up, not down. Your short shipments will keep going up, the challenge of managing inventory will go up. And finally, even if you earn just Rs 118 per transaction after managing all this complexity, is it really worth it? Will you forever be on a treadmill that keeps needing more and more transactions per day to cover fixed costs, that keep going up rapidly with scale? Breakeven is a distance away and profits a mirage.

Clearly, no hyperlocal grocery business will make money for a long time. My guess is seven-eight years out, if not longer. Unless a firm creates a uniquely Indian model— asset-light with low inventory, low complexity and combines it with a high-density consumer cluster—there is no rational reason for any of them to churn out a rupee of profit.

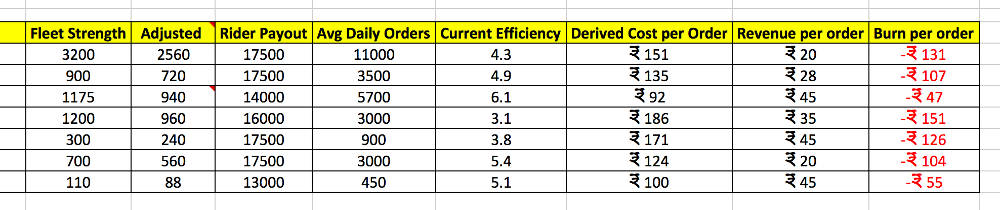

This treadmill effect has killed several hyperlocal delivery players already; the model could never have made money. Low network density, intense competition, and high attrition in delivery boys ensured they died quick (but painful) deaths. Here are estimated numbers for hyperlocal delivery startups in October 2015. The names have been blanked out. Half of these have already wound down, but the wastage is there for everyone to see. Mind you, these are losses that evaporate; these are not investments. These startups serve local businesses, i.e. there is no brand franchise or stickiness being generated as a result of this carnage of cash.

[As of October 2015. Source: A survey of hyperlocal players.]

[As of October 2015. Source: A survey of hyperlocal players.]

Fast-paced growth in most startups has proven to be like building a structure as the foundation keeps falling apart. Escape velocity takes on a whole new meaning when your math sucks like this.

The only thing that will work

So you need to work harder, be more innovative than the West. Your clone has to address uniquely Indian economics and mindsets. Unless you focus on thinking about how to create network effects and low churn (i.e. low or zero customer retention cost), you’ll never make money and your goalposts will keep shifting as the rising complexity of your business forces you to create an ever growing cost base.

What I find utterly baffling is that while our startup entrepreneurs put up Amazon, Uber and Airbnb as their idols, they never focus on how these folks did it. They never tune into the fact that Amazon’s founder Jeff Bezos knows that he is playing a thin-margin game and winning depends on how tightly Amazon is run.

It’s ironic that while Amazon prides itself on frugality, the clones in India are hiring people by the thousands, setting up fancy offices with free lunch for their teams. Their fixed costs, payrolls are nothing short of astronomical. A joke doing the rounds is that there are more top-tier McKinsey and Bain crop of consultants employed in Indian e-commerce companies than in the consulting companies’ Indian operations themselves.

Why do we need so many people? Do people add to the complexity and inflexibility of your operations or do they reduce it? Ditto for Uber. It runs a 50-country operation with much fewer people than Ola for its India operation.

Do Indian startups believe that gravity does not exist? Or is the Indian unicorn a winged horse, unbound by gravity?

Final words

What has happened in 2015 is good (see ‘Eight Things That Will Change for Startups in 2016’). It has shone light on our blind clones. But this is not the 2000 tech bubble. This time it’s different. Last time around there was no demand, no habit and no zillions of handheld devices on 3G and 4G connections that Indians wanted to stare at over 300 times a day.

We now enter the third generation of the startup ecosystem in India:

Generation 1.0 (1999 – 2007): Hype of the West + Hype of India

Generation 2.0 (2007 – 2015): Hype of the West + Hope of India

Generation 3.0 (2016 – 2023): Reality of India, the second largest internet market.

The issue this time is not the demand. The market is there for the taking. This time it is about the cost of doing business and how you build your business. Failure is a burden startups will have to bear. Most models are established. The math is visible. The complexity is not hidden. Now if startups fail, or if VCs continue to have blow-outs, there is no one else to blame.

Examples abound of good startups that are doing their work quietly, away from the media hype. Some are building world-class products and competing with the best in the world.

Businesses like Urban Ladder and CaratLane are aimed at organizing fragmented markets to create “online” brands with positive unit economics.

The same can be said of some vertical e-commerce players in the lingerie space or the social discovery platforms for fashion. If they are lean, these destinations will create sustainable value from aiding consumers discover merchandise.

Shuttl, I think, has found the perfect niche between poor experience with public transport and expensive cabs.

OYO Rooms too is actually filling a gap (assuming they will stop cash burn after having acquired their competitor).

In the Fin-tech space, if you look beyond payments, there are sustainable opportunities in online insurance that are ripe for startups to dis-intermediate and pass control to consumers so that they may compare and transact.

And finally, there are startups that have been around for a while now, and that continue to innovate and maintain their market share and economics. BookMyShow is a case in point that can charge consumers by being convenient.

The new ones that come up for funding will be asked tough questions. The fact that you fail to raise your funding rounds may be a blessing—it will force you to think harder and come up with a solution that fits the Indian market and circumstances. And then you are ready to win.