[If somebody graduated as a medical doctor in 1950, everything they learnt about liver diseases was proven or went obsolete 45 years later.

The Agnew Clinic 1889 by Thomas Eakins: a portrait of Dr. D. Hayes Agnew, professor of surgery, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.]

Much was left unsaid when Big Data in the Age of Biology was published here a few weeks ago. While it did touch upon the idea of half-life, it did not plead that the idea must be embraced urgently and that there is a moral imperative to it.

Those embedded in science define this as the time required for a given amount of a substance to reduce by half as a consequence of decay.

By way of example, people who practice medicine and pharmacology study the half-life of various elements in drugs to understand how long it will stay in the human body. They then attempt treatments based on this understanding. If a drug stays in the system too long, it may cause damage. If it stays for too little a while, it may not do the job.

Figuring the half-life of a drug in any individual is a difficult proposition. There are multiple variables at play from how a given drug interacts with a certain individual’s system to what may the individual’s system be like.

Much the same thing can be said about ideas; or the truth for that matter. What do we know about it? When Samuel Arbesman, scientist-in-residence at Lux Capital, dived to research it, one of the outcomes that emerged was that the “half-life of truth now is 45 years”.

He offers multiple pointers on how to look at it. For example, if somebody graduated as a medical doctor in 1950, everything they learnt about liver diseases was proven or went obsolete 45 years later. Does that mean what they were taught was wrong? Or did they drive themselves into obsolescence by not educating themselves?

The irony lies in that their obsolescence will be worshipped as “experience” by those outside the domain. That is how it has always been.

If morality be deployed as a tool to think through the issues here, it raises a few questions:

- Do those with obsolete knowledge bases have a moral imperative to continue their practice?

- Is there a moral imperative on each individual to reject those who are now obsolete?

- What role do regulatory authorities like the government have? For that matter, does the government matter?

May I submit that those who are in power will do nothing that will disturb the status quo. To the contrary, challenger narratives sound threatening to them. So while they may have a moral imperative to call it a day, they will do whatever it takes to keep challengers out.

But taking status quo for granted is a morally untenable proposition as well. Because accepting it allows monopolies to emerge and undermines entrepreneurship. If it is allowed, it strikes at the most fundamental of all human instincts—the right to choose how to live and the pursuit of happiness.

The Half-Life of Ideas

Those who are invested in power will do all they can to cling to it. That is why a silly idea raised its head in Delhi a few days ago—that a gag of some kind be imposed on the media. Apparently, because media outfits wield disproportionate clout, are prone to misuse it, peddle fake news and influence public opinion. Proponents of the argument shouted from every platform that mattered, that the media must be gagged.

Some sane counsel eventually prevailed and it was nixed.

In the interim though, the ensuing rhetoric attracted much attention, and led to vociferous debates. But, having been in the media business for as long, “amused” describes the emotion all this evoked. Like I wrote in my weekly column in Livemint, in today’s age, this proposal is best described as “ill-advised”. It was destined to crash-land. My smugness had much to do with conversations in the past with veterans in Indian politics.

They work off a principle—that there is a half-life to political ideas in India. So, they pick their battles wisely.

How all this works was recounted over much jovial banter one evening by a gentleman who was nominated to the Rajya Sabha a few years ago. While politicians are elected for a five-year term, most are acutely aware their half-life in office is actually a little less than three years. The math is very simple.

a. The first six months of an elected politician’s career is the honeymoon period with those who voted for them. Their mistakes are pardoned; the people imagine there is a reason why they do things a particular way. Suave politicians know this. That is why the toughest calls they must take during their terms are taken during this period.

b. Once the honeymoon is over, silence follows. People are now waiting for the much-promised big bang changes to fructify. Politicians though know change takes a long while. They know their constituencies will start to get impatient, but will wait a little longer. In India, this period will last 12 months on the outside. By then though, 18 months of a politician’s five-year tenure would have passed.

c. This is the time political veterans know, snipers will take position and start taking shots. The opposition will scrutinise every decision and tear it to shreds. As the days go by, the din for crucifixion will grow louder.

Policymaking is one thing; implementing and waiting it out until change begins to show is another. To that extent, the earlier they move to make a decision and implement it, the better off they are.

Once 36 months have passed, they know that nothing they do will see the light of day while they are in office. This is also the time when the mainstream media and voters start to lament that the much-promised changes haven’t been fulfilled. But politicians don’t care much. This is the time to start prepping for the next elections. Two years may sound like a long time away, but in a democracy as chaotic as India’s, it takes time to prepare for an election campaign. What people perceive as promises that were reneged upon must be repacked. New ways to hammer away at the opposition must be strategised.

All this places into perspective why a half-baked idea such as policing fake news had to be aborted. If this idea had been announced earlier, much like the ill-thought through demonetisation was, it may perhaps have sailed through with much applause. After all, everybody is concerned about “fake news” and the implications of it all on “impressionable minds” in this age of unreasonable technology.

My takeaway from this episode was that after listening in to a story and before breaking out into wild applause, it may make sense to pause a while to think over the narrative that has been sold. It may just be re-packaged snake oil.

This is true not just for individuals, but for entrepreneurs and the entities they run as well. It cannot be dictated by the popular mandate. Their raison d’être is not just to survive, but to thrive. To do that, they know they must ignore half-baked ideas that have no significant half-life.

The Doubling Time

The converse of half-life is the Doubling Time—also called the Rule of 70. This is the period of time it takes something to double in quantity.

The doubling time of medical knowledge was 50 years in the 1950s. By 1980, it had come down to seven years. In 2010, it was three-and-a-half years and by 2020, two years from now, it is projected to be just two months. That is why those at the frontiers of the domain are exasperated and wondering what it may take to prepare people in the field to cope with changes.

Doubling Time is a concept that can be extrapolated to understand whether or not to apply an idea across other domains as well.

Muzzling the media in the 1970s worked well. That was a different India where most people had no access to technology, the population was dramatically poor, and any balderdash could be sold to the masses.

If the idea of Doubling Time is applied to India’s GDP, as compared to the late ’70s, large numbers of people have moved out of poverty and have moved into an altogether different quadrant. They are now part of the lower middle class and the middle class. Indeed, there still are 500 million poor people in India. But they are getting out of the morass.

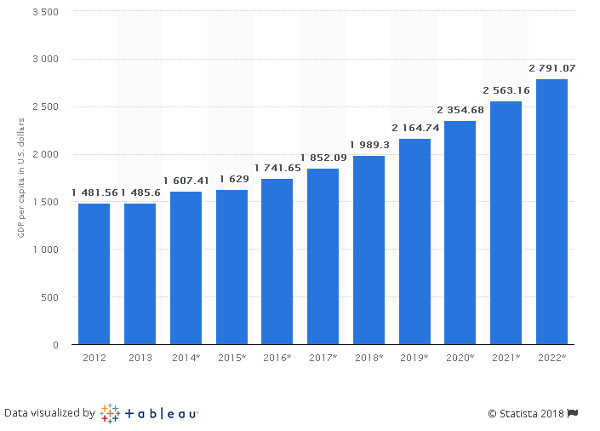

The Doubling Time effect will ensure that at an average projected growth rate of 7.5% in GDP, the Law of 70 (70 / Average Number) will ensure that in just about nine years, India will be a middle income country. This means an average per capita income of $2,791 by 2022.

It is currently at $1,852 and was $1,481 in 2012.

India: GDP per capita in current prices from 2012 to 2022 (in US dollars)

[Source: statistica.com]

If people with per capita income at $1,852 started to shout foul when the powers that be thought they could be muzzled, it is unlikely they will tolerate absolutely anything as they get richer and move up to $2,791.

When looked at from an entrepreneurial prism, it means a few things. It opens up a market, and much like the government can’t get away with things, businesses will not be able to either. So, while silly ideas can be rejected outright, promises cannot be reneged upon. People are growing richer and have the staying power to fight longer- drawn battles.

Sure, governments may choose to impose fines on an entity registered within the borders of a country, but how will it deal with digital nomads? These are people who choose not to be residents of any one nation, are constantly hopping from one place to another, and live in a parallel universe that law-makers haven’t begun wrapping their heads around.

There is much that is changing and who is to know what the impact of the Doubling Time may be on economies?

Dunbar’s Number

One way to look at it is through the eyes of Christian Lange, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1921. There is a middle path. “Technology is a useful servant, but a dangerous master,” he once said.

This ties in to the thought that all ideas have a half-life and the Doubling Time of knowledge has multiplied exponentially. Denying this would be silly; embracing it totally would be ridiculous as well. That is why Dunbar’s Number, coined by anthropologist Robin Dunbar, is a good thumb rule to go by.

Dunbar studied why primates spend so much time grooming. Based on his studies, he could roughly predict how large a social group a primate can form based on the size of its frontal lobe. On studying the human brain, he proposed, humans can at best handle social groups of up to 150 people. Anything larger gets too complex.

How outdated Dunbar was and how silly he sounds in a world where social media networks allow you to connect with people in the thousands is a point commentators have made. But Dunbar sounds like a prophet now that Facebook is under the scanner, Google is being looked at suspiciously, and people are wondering what trick Amazon may have up its sleeve.

He was right. There are only so many people and their ideas we can keep up with. Their ideas have a half-life. While the Doubling Time of knowledge that is accumulated may go up, there is only so much our heads can hold. More pertinently, what ideas do we hold?

This is where relevant networks are needed. But there is only so wide our networks can go to stay relevant, as Dunbar has proven. Dunbar’s Number has been studied in much detail over the years and the patterns that emerged out of six billion calls made by 35 million people through 2007, Dunbar’s Cluster was proposed.

This suggests that an individual is very close to only five of the 150 people s/he can maintain contact with. The next layer comprises 10 people. Outside this circle, there are 35 who matter. The final group of people with whom one can maintain any meaningful contact, tots up to 100.

In many cases, people are unable to make the 150 connections they are capable of forming. They imagine, however, that there are large networks of people they have access to because of their presence on social media.

Contemporary wisdom has it that every entrepreneur must stay abreast of all ideas, keep learning all the time, and have a well-oiled network in place. It seems, the technology to propel all of this exists. What we do know, however, is that when put in the wringer of half-life, Doubling Time and Dunbar’s Number, this proposition does not stand to scrutiny.

There are a few things though that do stand to scrutiny. Nassim Nicholas Taleb put it out as a list of “the sins to remember” and ones every entrepreneur must commit not to have: Muscles without strength, friendship without trust, opinion without risk, change without aesthetics, age without values, food without nourishment, power without fairness, facts without rigor, degrees without erudition, militarism without fortitude, progress without civilization, complication without depth, fluency without content.