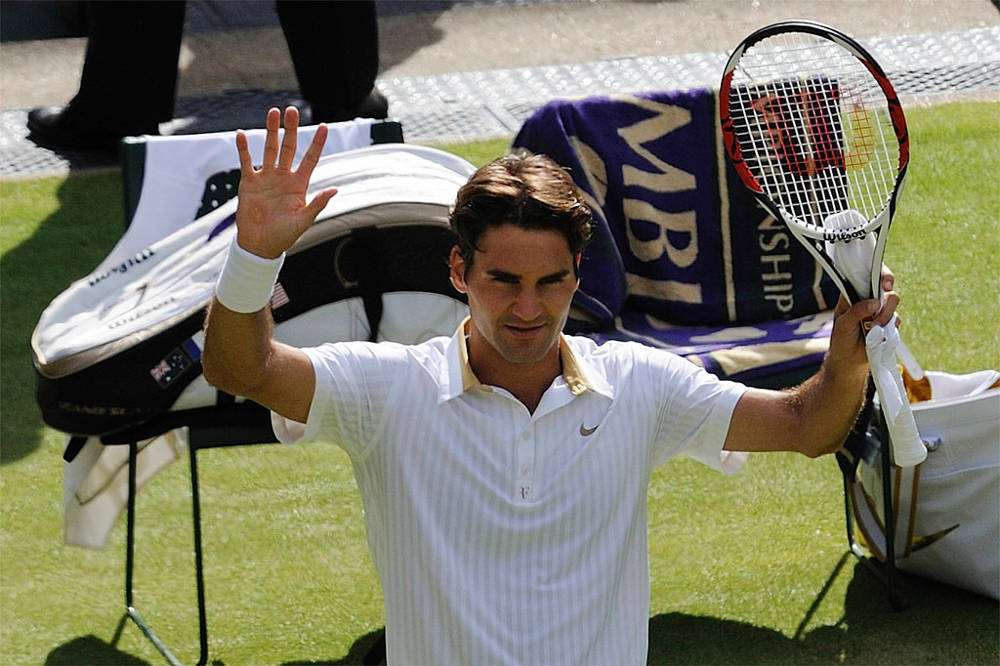

[By Justin Smith under Creative Commons]

A few hours from now, Roger Federer, a man aged 36, will stride towards the Centre Court to take on the 28-year-old Marin Cilic in the finals of the Wimbledon. If Federer loses, headlines, commentators and writers will speak of what a brave battle he fought to get this far. And if he wins, people will gush about how he beat the odds once again. And more speculation will follow on when will the best athlete the game has ever seen retire.

Pushed to the wall, may I submit Federer will win the game later this evening? And that he isn’t anyplace close to retirement. Not for anything else, but because all evidence suggests he will win the game. But this is a narrative nobody, me included, wants to buy. Because it isn’t a sexy narrative to tell. What all of us want to hear instead are stories of humans who defied the odds and got to where they are on the back of determination and talent, after having fought all that is railed against them. But this is unappetizing.

People who understand this best are storytellers. If some context be needed, the best storytellers work on a simple premise. Leaf through the pages of any newspaper, magazine or book that documents the rise or fall of a legend. Inevitably, successful plots that get the most attention follow familiar terrain. The central protagonist starts against the odds, dreams big, meets with failure, keeps at it, learns from the mistakes, finds a mentor, finally makes it to prime time and is now in philanthropy mode. Alternatively, they are to the manor born until they go philandering and squander it all away.

How much more linear can it get? But everyone loves it. Because the human mind craves the familiar. Examples?

While Sachin Tendulkar is now spoken of as a case study about the victory of the middle class, what memories do you have of Vinod Kambli? Both started to play cricket together. By all accounts, Kambli was the underprivileged one. The son of a machinist and a kid who grew up in a poorer suburb of Mumbai as compared to Tendulkar, newspaper reports have it he was more talented than Tendulkar. These reports also have it that Kambli lost the plot and started to implode, just three years into his professional career.

Angry epitaphs were written in trying to seek a narrative, including one that his career was killed by self-serving cricket administrators. For instance: “No one should take offence if a machinist’s son displays attitude by sporting earrings or playing pranks: the rigours of a long journey can leave strange scars, the need to make all kinds of statements, the incessant fumblings to forge an identity. What must be remembered is that he has made the journey fuelled by talent alone. And talent, in any field, is rare; it ought to be fostered and respected.”

It is a narrative we like to hear. It sounds familiar. That the poor will be poor because they can be trampled upon.

If that be true, what explains the phenomenon that is Tendulkar? He too got on the crease with Kambli. But as history has it, Kambli was a better player, all thanks to the circumstances he grew up in: “The small patch of land that served as his first cricket pitch was surrounded on all sides by high-rise buildings. The scoring system was dictated by the lack of space, and the higher a batsman hit the ball into the buildings the more runs he scored. It explains why Kambli was one of the best over-the-top hitters of spin bowling.”

Spare a few moments on the thought though on how much more ridiculous can it get? In poring over Tendulkar’s background, at least in financial terms, their backgrounds sound only marginally different. And if familial ties are anything to go by, again, on paper at least, Kambli’s was a more closely knit family.

About Tendulkar, what most people know of is that he owes much to his older brother Ajit. He was a mentor and coach to the young boy in his early days. What few people know is that Ajit was his half-brother because his father re-married his first wife’s sister after she died, soon after Sachin was born. He grew up calling her mavshi (aunty), not mother.

And ironically, in their late teens, Kambli and Tendulkar caught the eye of the legendary Indian cricket coach Ramakant Achrekar, who took them under his wing. Had Tendulkar failed though, the narrative that surrounds the legend that is Tendulkar and the failure that is Kambli may have been different. All the reasons ascribed to Kambli’s failure now may perhaps have been extrapolated to Tendulkar.

This phenomenon, dubbed the “Narrative Fallacy”, is among the most basic and well-documented ones. It has been exploited the most by storytellers of all kinds, smart investors, and most recently by Artificial Intelligence (AI). People need narratives to make sense of what is a chaotic world. For some more perspective on the Tendulkar-Kambli saga and how ought we look at the phenomenon that is Federer, I turned to Sukhwant Basra.

The former sports editor at Hindustan Times, he is now a tennis coach and is at work with India’s prominent tennis player Leander Paes to create an academy to groom talent. Between the both of them, they have seen and interacted closely with Federer, Tendulkar and Kambli. And the consensus view, the both hold is this:

- As things are, age is an over-rated virtue. If any evidence be needed, consider Paes. He is 44 now, is widely considered among the best players to have dominated the doubles tennis circuit in the world, continues to play, and has the best record among the top three Indian players.

- Talent is over-rated as well. If talent was all it took to be top dog, we wouldn’t be talking of Federer in hushed tones or written Kambli off.

I asked Basra to put it into perspective because Paes and he have discussed it at length. To Basra’s mind, what it boils down to is this. Kambli could hit the ball out of the park in his early years not because he was born talented, but because he practiced in cramped quarters. It compelled him to create a style that would allow him to stay on the crease. This meant hit the ball as high and as hard as he could.

Tendulkar, on the other hand, lived in a suburb where he had access to wider parks and practiced a game of a different kind. So, when compared, Kambli looked more talented to the untrained eye. But what Tendulkar had, Federer possesses, and Kambli lacks, is focus. It compels them to “practice deliberately” for long hours. As for talent, they have it in equal measure.

Much the same thing can be said of Paes. He has stayed in the game for as long as he has because his father understood the nuances of what lies at the intersection of sport and medicine. He inculcated deliberate practice into the young Paes’ routine. Talent alone could only have taken him so far. He too, practiced deliberately.

Add to deliberate practice advances in medical science and technology over the past decade. It insists that if an athlete knows how to train smart, they can stay on top of their game for longer than most humans like to believe. This is very different from the romantic notions of sport our minds love. In Federer’s case for instance, Basra points out reports have it his team uses the Matrix Rhythm Therapy (MRT). This allows them to map his body when it is at its optimum.

The premise here is that the body has a certain rhythm. When interrupted by strenuous activity, like a long game for instance, it tires out and the chances of injury go up. So, at the end of each game, they map what the muscles in his body look like as against what it was at its optimum. Armed with this insight, they then get down to work on just the right places that need to be restored.

This means, even micro traumas that may not trigger a response from the body in the form of pain, can be detected before they blow up into an injury. These are advances of the kind people like Paes understand as well and deploy, among other things, to their advantage. That is why people like Federer and Paes have lasted as long.

There are other nuances Basra pointed to on how the game has evolved. The evolution of the tennis racquet, for instance, has changed the nature of the game. Once upon a time, balls used across different surfaces were not uniform. But there are standards now. It allows players to practise for the kind of surface they intend to hit.

But these don’t make for good narratives. There are no heroics embedded here. Instead, these sound like clinical tales bereft of humans defying the odds. Be that as it may, it is a truth the game and the players have acknowledged—those who have kept pace and are on top of the pyramid.

As for sports critics and die-hard fans, they either don’t get it or choose to look the other way.

What continues to remain embedded in everyone’s mind is a man called Bjorn Borg who retired at age 26, the tantrums of John McEnroe, the sheer talent and genius of Boris Becker and literature of the kind written way back in 2006 by David Foster Wallace that spoke of Roger Federer as religious experience. What can get more compelling than that?

“The specific thesis here,” Wallace famously wrote, “is that if you’ve never seen the young man play live, and then do, in person, on the sacred grass of Wimbledon, through the literally withering heat and then wind and rain of the ’06 fortnight, then you are apt to have what one of the tournament’s press bus drivers describes as a ‘bloody near-religious experience’”.

Again, it boils down to the fact that us humans love stories. To sum it all up, Basra says, “Fans are fools and get emotional about their idols and want them to live up to some image of the past. But their idols have moved on from the past.”

That is why, we will do well to get past our Narrative Fallacies as well. If we don’t, there is a real danger. Advances in technologies like Artificial Intelligence are dumbing things down to create platforms of the kind where you hear only what you choose to hear. Amazon’s algorithms are learning what you may like and compels you to shop more. Facebook is beginning to understand the kind of people you like to be friends with and goads you towards them. Google understands your preferences and shows you just that. Effectively, they are at work to create filter bubbles around us to keep us where we are, even as they have moved on.

It is inevitable then we work hard to stay relevant. Else, our prospects may be as gloomy as that of Kambli. Or it could be as bright as Federer—who is destined to win Wimbledon later today because he has crafted the future.

(This is adapted from The escapades of Indira Gandhi, the romance of Roger Federer and originally published in LiveMint).