By Jens Kastner

Imagine a city of the future, a city where commuters are chauffeured to work by self-driving cars and where artificial intelligence systems control every power plant, traffic light and light bulb, making road accidents, power cuts and even traffic jams a thing of the past. Where you can spend as much time in a virtual reality as you do in the physical world.

Thanks to 5G, the latest protocol for mobile communications, this vision may be realised much sooner than you think. The world’s leading telecom companies are already testing the next generation of wireless internet and the first 5G services could be rolled out as early as 2019.

The new networks are expected to be 100 times more efficient and many times faster than 4G, according to UN telecom body the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). This will open a vista of new technological possibilities.

The gains in network speed and reliability will enable billions of internet-enabled devices to connect and coordinate themselves seamlessly in real time. On the roads, self-driving cars will be able to sense each other’s movements and adjust their speed and direction to avoid collisions.

Beneath the asphalt a vast network of smart sensors will control cities’ water, power, waste and transport systems, unlocking vast gains in efficiency.

However, the transition to 5G not only promises to improve public services and people’s quality of life; it could also be a game-changer for businesses and governments across the world. By 2035, more than $12 trillion of economic output will depend on 5G worldwide, analysts IHS predict, and the 5G value chain alone will support 22 million jobs. With key emerging industries like the Internet of Things (IoT), virtual reality and autonomous vehicles all relying on the rollout of 5G, the countries and operators that take the lead in mastering and deploying these next-generation networks are likely to gain significant financial and competitive advantages.

Like the transitions to 3G and 4G, the battle for 5G supremacy is being fought mainly by the leading telecom players including European companies Ericsson and Nokia, Samsung of South Korea and the US’s Qualcomm. But this time, China’s Huawei and ZTE have also emerged as forces to be reckoned with. And they may have a decisive impact on the outcome.

China’s 5G Dream

China’s telecom firms were little more than also-rans during the transitions to 3G and 4G—and paid the price for it. Both they and the Chinese government appear determined not to let that happen this time.

The government is keenly aware of the potential opportunities offered by the transfer to 5G and has been preparing for it for years. It founded the IMT-2020 (5G) Promotion Group as early as 2013. This government body is responsible for coordinating the government agencies, operators, vendors, universities and research institutes working on new wireless internet technology.

Making China the global leader in 5G is also one of the cornerstones of Made in China 2025, the ambitious industrial strategy launched by the Chinese government in 2015 that aims to make the country the world’s leading high-tech manufacturing power. As the factories of the future are sure to depend on 5G connections to function, the government knows that leading and shaping this technology will bring enormous benefits.

A recent report by the China Academy of Information and Communication Technology (CAICT) made clear what is at stake for China. It predicted that the rollout of 5G infrastructure would drive RMB 6.3 trillion ($947 billion) of economic output in the country by 2030.

The country’s telecom groups have answered the call and are expected to spend a combined RMB 2.8 trillion ($420 billion) on building out 5G mobile networks between 2020 and 2030, according to a study from the CAICT published in June. Such vast investment is understandable given the scale of China’s internal market—the Asian superpower had 950 million 4G network users as of the end of September, almost triple the entire US population.

The Chinese government’s planning is starting to pay off, as China nudges ahead of the pack in the race to make the 5G world a reality. In November, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology announced it had officially launched the third stage of trials for 5G networks and that the country’s three major wireless carriers—China Mobile, China Unicom and China Telecom—would begin installing an initial commercial version of 5G networks in 2018.

Huawei and ZTE, already well positioned to become major global players in 5G due to the wide adoption of their mobile equipment across Asia and Europe, have also shocked their rivals by the speed at which they have developed new network technology. At the PT Expo China 2017 in September, Huawei became the first company worldwide to demonstrate a new device combining several key 5G technologies, which is capable of transferring data at 32Gbps—a speed one German newspaper called “crazily fast”.

[Xu Zhijun, Huawei's rotating CEO, introduces the company's 3GPP 5G pre-commercial system at the World Internet Conference in Wuzhen, Zhejiang province, China, in December]

“Huawei demonstrated one big thing: they are ready for the next generation of mobile telecom, not only in theory, but also in practice,” read a report by German online publication teltarif.de.

What the report added was even more important: “Huawei has presented a major contribution for an industrywide standard for 5G key technologies and their inter-operability.”

Setting New Standards

It is crucial that Chinese companies leverage China’s pole position in the 5G race to shape the global standards in their favour. If they fail to do so and the standards stray too far from what they have been working on, there is a real risk that large chunks of the massive investment—in the billions of dollars—Chinese companies have already spent on R&D for pre-commercial 5G products could be lost.

“It will be strategically important for all equipment vendors, Chinese and otherwise, to get ahead of 5G standardisation because 5G will require a more complex ecosystem of partners to enable services than previous generations of mobile networks,” says Malcom Rogers, a telecom market analyst at UK-based market intelligence provider GlobalData.

“Working early to shape 5G standards will cut down on future R&D costs, establish valuable partnerships with operator customers and reduce time to market once 5G is ready for commercialisation.”

According to Rogers, equipment vendors, by working with partners can ensure that their early investments in trial 5G equipment will be able to be deployed without any major overhaul once 5G has been fully standardised. Such partners include mobile network operators, handset chipset manufacturers, cloud integrators and IoT platform providers, as well as standardisation and regulatory bodies. Their early investments include antennas, base stations, core networks, backhaul and data centres.

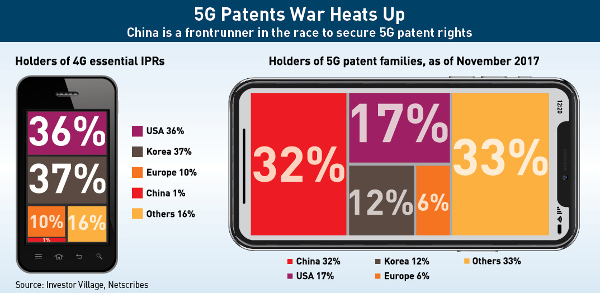

Shobhit Srivastava, an analyst with India-based technology market researcher Counterpoint Research, points out another key reason why China is so committed to shaping the development of 5G. Intellectual property rights (IPRs) related to 3G and 4G, Srivastava says, are mostly owned by Ericsson, Nokia and Qualcomm.

The result of this is that Chinese companies pay huge amounts to the foreign players in royalties. Exactly how much this amounts to is difficult to estimate due to the complex cross-licensing deals between the companies, but is almost certainly in the billions of dollars.

“So, they are in a real rush to get many IPRs that are going to be essential for the future 5G standards. This is not only to save on 5G-related royalties but also to cross-license their 5G IPRs against IPRs in the conventional telecom technologies,” he says.

Fifth Time Lucky

When it comes to the importance of setting global standards, the Chinese players have learned from bitter experience. China played virtually no role in the development of 1G and 2G networks in the 1980s and 1990s, with the technology being dominated by Ericsson, Nokia and Qualcomm.

In the 2000s, when the rest of the world started to move onto 3G, which allowed mobile users access to the internet, China decided that it would shun dependence on Western technology. Instead, it developed its own 3G standard, TD-SCDMA, rather than adopting the standards—CDMA2000 and WCDMA—being used elsewhere. But TD-SCDMA was not adopted by any telecom operator other than China Mobile even though it was recognised by ITU as a 3G standard.

“As the TD-SCDMA handsets only worked on the China Mobile network and therefore couldn’t be used for roaming, consumers were reluctant to sign up. Chinese planners had envisioned that the sheer economics of scale of the Chinese supply chain would convince the rest of the world to sign on [to TD-SCDMA], but it didn’t,” says Edison Lee, an equity research analyst at Jefferies Hong Kong Limited.

“Qualcomm managed to stay ahead of the pack during the migration from 3G to 4G, but when in 2012 the ITU started thinking about 5G, China realised that 5G is going to be a single global standard that will no longer be built on legacy technology. This gave China a big, brand new opportunity to own a certain share of crucial IPRs,” he adds.

The Chinese players are doing everything they can to seize this opportunity. At the Mobile World Congress 2017 last February, Huawei, Intel and their telecom operator partners announced they would work together to drive globally-unified 5G standards. They also said they would create a unified 5G industry chain, from chips and terminals to network infrastructure and test equipment.

But before Huawei has any chance of doing this, the Chinese will first need to win a much bigger battle against their US rivals.

What’s the Frequency?

Lee notes that besides the race for 5G IPRs, there’s also fierce competition between Chinese and US interests in terms of what frequencies the eventual global 5G networks will be working on. Whereas China is enthusiastic about the medium frequency, which offers wide coverage, the US supports the super high frequency. This makes it easier for operators to find big chunks of unused spectrum, but offers shorter transmission distances and is more vulnerable to blockage by objects such as trees or houses.

“US academia believes they have achieved a breakthrough to overcome this, so that they can use super high frequency instead of the lower frequencies that are heavily contested in the US by both commercial and military uses,” Lee explains.

“The Chinese, in turn, fear that a turn to super high frequency will once again allow the Americans to outmanoeuvre them in terms of core telecom technology. The Chinese will thus try to push for 5G at medium frequency and scale up the industry in order to reduce the cost, so that the rest of the world will not lean toward adopting super high frequency,” he adds.

So serious are the struggles taking place behind the scenes, it is expected that the first 5G networks will go live in 2019 without any agreement on standards being reached. The battlefield on which this regulatory fight will play out is a task force under the ITU called the third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), which is meant to broker agreements on what performance requirements 5G will have to achieve.

The 3GPP breaks the project down into working groups. Each working group will come up with engineering solutions for each component backed up with trial data in order to reach consensus as to which proposal is the best. These will ultimately be combined into a standard.

“It is a consensus building group and supposed to be democratic, but if you rely on consensus building, it will take forever,” comments Lee. “So, they narrow down to the two or three best solutions and if the group can still not agree, they go for a vote.”

According to Lee, China started participating in these groups in 2012. It has since been “pretty aggressively” increasing the number of its people in the committees and sub-committees, so that by now many of them have Chinese chairmen and vice chairmen.

“Theoretically, these chairmen would not have extra weight and are supposed to be just administrators, but in organisations like the UN where lots of countries participate, there are many countries that will never submit actual proposals,” Lee says. “So, when China needs support on one solution that is not dramatically inferior to the other solutions on the table, of course, China will try to get support from their smaller country friends for the vote.”

China scored an early victory in the working groups in November 2016 when the 3GPP decided to make China’s Polar Code error correction technology part of a 5G global standard. The decision was hailed throughout China as proof that the country is a contender in the race to define and develop 5G, but set teeth gnashing in the US.

The US Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which can barely hide its deep dissatisfaction with the 3GPP’s standard-setting process, put out a terse statement in the wake of the decision. Though the statement did not name China, it hinted darkly that some countries were seeking to control how global standards were being set.

Western Headwinds

The battle over standards is not the only area where the Chinese players are encountering strong opposition from the US. Huawei and ZTE have been banned from America’s telecom infrastructure market since 2012 on national security grounds.

The companies have responded by focusing on other key markets such as Australia, India, Japan, Latin America and the EU. There they are giving Ericsson and Nokia a run for their money on their home turf, according to Neil Wang, Greater China president of researchers Frost & Sullivan. However, even in these markets the Chinese groups risk being shut out due to their lack of close partners within the industry.

“The challenge remains that the major rivals like Ericsson, Nokia, Qualcomm, Samsung and Verizon own many more patents than Huawei and that market and technical alliances are made between those competitors. Examples are Verizon’s association with Samsung and Ericsson, and AT&T’s partnership with Nokia,” says Wang. “Chinese players still have a certain distance from them in the eyes of the outside.”

Huawei is working closely with 5G consortiums that include US companies like AT&T and Verizon. But, according to Rogers from GlobalData, this pales into insignificance compared to the massive amount of collaboration occurring between Japan, Korea and the US as these markets aim to be the first to launch commercial 5G services.

“Huawei should continue to track what the US is doing, as it will likely influence the markets into which it can sell,” Rogers warns.

Unclear Signals

With the race for 5G entering the final furlong, the eventual outcome still looks far from clear. According to Lee, there is a high likelihood the fight over patents will eventually end up in the courts. However, Lee believes it is a safe bet that China’s initial share of 5G patents will be somewhere around the 10% mark.

“While I think they are targeting a 20-25% share, 15% is certainly achievable in the intermediate term, which would put them in a much stronger position in the competitive landscape than during 4G,” he says.

The outcome of the battle over frequencies looks equally uncertain. The US government currently appears to be digging its heels in, as the FCC has already allocated super high frequency for 5G. But US industry does not appear totally confident that the US will win this battle. In June, Fierce Wireless reported that US telecom operators have been pressing the FCC to revisit medium-band frequency to make sure US technology can be aligned with the frequency range if necessary.

Given that the availability of free spectrum is a very big factor for telecom operators, Lee believes that a compromise may be reached, in which the world settles for medium-to-low frequency with super high frequency being used as a supplement in densely-populated city centres.

The 5G world may not run on Chinese rules, but there is no doubt that the balance of power is tilting eastward. And the race for 6G is about to begin.

[This article has been reproduced with permission from CKGSB Knowledge, the online research journal of the Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB), China's leading independent business school. For more articles on China business strategy, please visit CKGSB Knowledge.]