[Clockwise from left: Mother of Georgia - photo by Unrecognizablepineapple, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons; Metekhi Church - Photo by Rikitza, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons; Sighnaghi town, photo by Uma Narain]

Georgia caught my attention as I scanned the map for a sylvan, restful and safe holiday destination. It ticked many boxes.

With the towering Caucasian mountains in the north, the Black Sea to the west and the Caspian Sea to the east, it promised a picturesque landscape.

I am also intrigued by how geography shapes a country’s history and culture. Georgia sits on the cusp of Eastern Europe and West Asia, and shares borders with Russia, Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan—it was a hub on the silk route and figures prominently in current geo-politics. Despite successive long periods of Byzantine, Mongol and Soviet influences, it has retained a native character and identity. And of course, I was also enticed by the idea of sampling Georgian cuisine and wines—emerging global favourites.

The final push to pick this as my holiday destination came from the sweltering Mumbai heat and the promised respite of crisp mountain air—the baad-e-naseem (gentle breeze) as Faiz would say.

A six hour flight from Mumbai via Kuwait brought us to Tbilisi (there’s a direct flight from Delhi). For Indians with a US visa, entry to Georgia is visa-free—a pleasant surprise. For others, the process is hassle free. It takes just 3-4 days to get an e-visa.

With five days at hand, a relaxed and flexible itinerary, and lots of warm clothes, I was ready to explore.

Tbilisi: A City of Stories, Streets of Memory

We prefer staying in the town centre. In Tbilisi, this is Rustaveli Avenue, a 1.5-km-long central thoroughfare stretching from Freedom Square to Rustaveli Metro station. The street is itself an artefact, bursting with history, art and culture, and with several iconic monuments.

The street is named after the 12th century poet Shota Rustaveli whose epic poem ‘The Knight in Panther’s Skin’ was dedicated to Queen Tamar, the first woman to rule with the title ‘king of kings’. Her 29-year reign is celebrated as a Golden Age of stability and cultural renaissance before the invaders came. The poet Shota Rustaveli is revered as the “coronation of thought, poetic and philosophical art of medieval Georgia”. Many streets, institutions and monuments bear his name.

Art of Dissent

Despite the drizzle and bone-piercing winds, we took a walking tour. The highpoint was 7, Rustaveli Street, which houses the new cultural hub, Georgian Museum of Fine Arts—it has Georgia’s largest private art collection which had remained underground till recently.

[The Georgian Museum of Fine Arts]

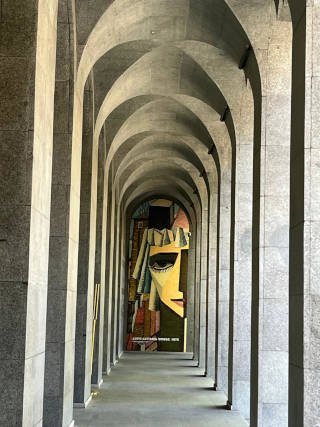

The sidewalks of Rustaveli Street are adorned with cute miniature figures of musicians and performers perched on small pipes. The museum is a Modernist structure with an eagle atop the facade and a horizontal corridor with angular arches that end in a huge painting. No English-speaking guide was available and I thought this is for the best because art needs to be sensed, not explained. The collection is chronologically displayed on three floors and we decide to start from the top floor.

[The arched corridor of the Georgian Museum of Fine Arts]

The brochure says the museum’s mission is “to unite and promote Georgian, Soviet and post-Soviet art in one art institution… many of the exhibited works have never been shown to the wider audience”. During the Soviet era, only works that conformed to the state agenda were encouraged. Life had to be shown happy, heroic and optimistic. Yet, some artists found subtle ways to express dissent and realism. And some of these works hit me hard:

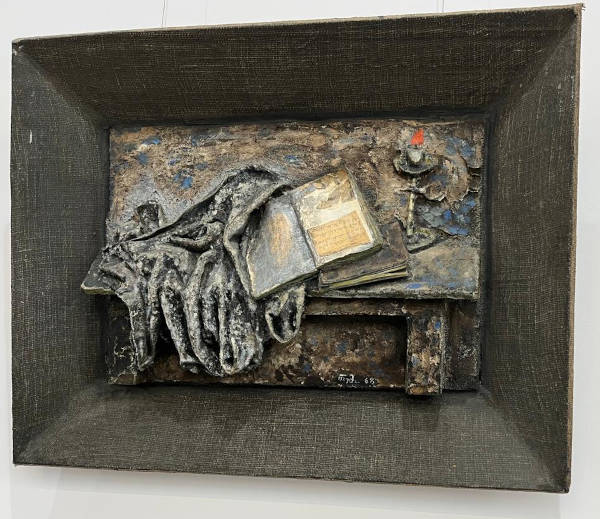

[Temo Japaridze’s The Dust of History (1968)]

[Temo Japaridze’s Broken Smile (1975) and Crucified Generation (1965)]

Temo Japaridze’s The Dust of History that shows dismembered limbs, a tattered book and a flickering lamp on a dull background; Broken Smile (1975) that shows a sad clown; and Crucified Generation (1965) that shows the crucifixion of a young boy.

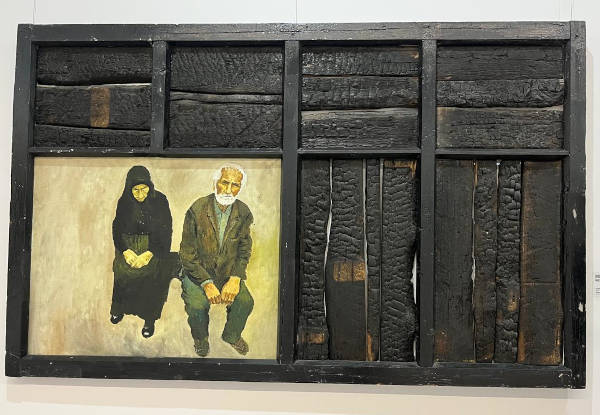

[Thrown out. Refugees (2010) by Gogi Chagelishvili]

Thrown out. Refugees (2010) by Gogi Chagelishvili, which shows a seasoned wood wall with shut doors and windows and an old couple seated on a bench in a small opening, the man wearing a skull cap and the woman a hijab.

[Portrait of Wife (1975) by Otar Chkhartishvili]

Portrait of Wife (1975) by Otar Chkhartishvili which shows a woman’s role and identity through her anatomy—a sad face, rounded breasts and an elongated reproductive passage.

Warmth Worldwide—‘the kerosine is running out’ (2004) by Vladimir Kandelaki shows a haggard old woman at the stove with pots and pans on the wall.

Pictures of cars belonging to Hitler, (2012) & Stalin (2012) by Oleg Timchenko with telling captions: ‘He alone who owns the youth, gains the future’ and ‘the death of one man is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic’.

I came out humbled and in awe of the courage of these artists, chroniclers of fortitude amid suffering and the real history of Georgia—more compelling, more sensitive than any account captured in words.

Ironically, just across the street I saw protestors outside the Parliament of Georgia. A passerby explained: “People are angry with the ruling party for the breach of the election promise. The vote was for a pro-European and pro-Western policy (aspirations for EU and NATO membership) but the government has tilted towards Russia.” The protestors were also questioning the government’s decision to allow Russians who fled to Georgia to stay without a visa.

[St George slaying a dragon, Freedom Square]

Freedom Square, the eastern end of Rustaveli street, is the site of declaration of independence in 2003, when hordes of people carrying red roses gathered to mark the non-violent change of power—the so-called Rose Revolution that paved the way for democratic reforms. It is now a busy intersection of six streets with a column bearing the statue of St George slaying a dragon.

[Outside the Opera Ballet Theatre]

[Rustaveli Theatre]

Unfortunately, the Opera Ballet Theatre, a stunning late 19th century Moorish style structure and the adjoining baroque-rococo style Rustaveli Theatre were closed for casual visitors. But the famous stone church, the Kashveti (‘to give birth to stone’) Church of St George, was open. The Orthodox church had survived attacks that destroyed other monuments. It has beautiful frescos painted by the well-known Georgian painter, Lado Gudiashvili.

We headed to the Pasanauri restaurant for a well-deserved meal: Saperavi wine, a delicious Georgian salad that I decided I would order at every meal, Georgia’s signature dish Khachapuri (a cheese-filled fresh baked crispy bread), and deliciously grilled juicy meat.

Old Town: A Living Museum

The next day, we took another walking tour over cobbled streets to see monasteries, churches, forts, sulphur bath-houses, and the famous puppet theatre in the Old Town. We pinned the monuments on Google Maps and followed the directions, starting from Freedom Square.

[Metekhi Church and King Vakhtang Gorgasali astride a horse - Photo by Rikitza, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

Our first stop was Meidan Bazaar, a cave-like underground market selling artefacts, old paintings, spices, honey, wine and trinkets. We then walked to the Mtkvari river front. On a cliff on the left bank sits the Metekhi Church, with a statue of King Vakhtang Gorgasali astride a horse. He ruled Iberia (present day eastern Georgia) in the 5th century, founded Tbilisi and also several monuments in the city. Across the river is the beautiful Rilke Park. One can take a scenic cable car ride from the park across the river, to the hilltop statue of Mother Georgia, but it was closed for repairs.

[Mother of Georgia - photo by Unrecognizablepineapple, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons]

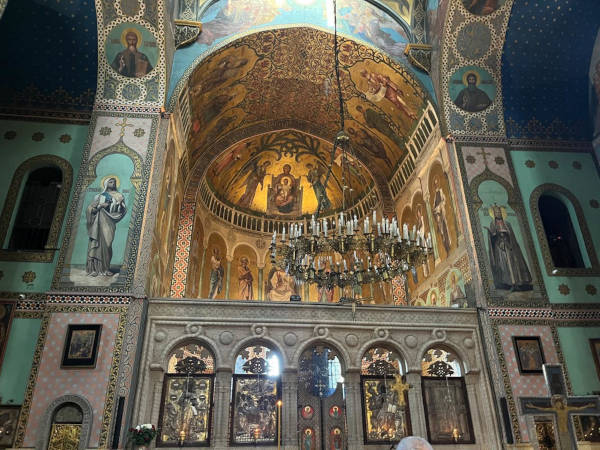

[Inside Sioni Temple]

We walked back to the Old Town to see the revered Sioni Temple for Mother of God, built by King Vakhtang. Preserved at the temple is the venerated Holy Vine Cross of St Nino (aka the Georgian Cross, or the Grapevine cross), a major symbol of the Georgian Orthodox Church. This was the first region in the world to declare Christianity as the official religion in the 4th century, and to adopt St Nino’s cross ‘with slight drooping horizontal arms’. According to legend, Nino, a Cappadocian nun, received the message and the grapevine cross, as a benediction from Virgin Mary, to spread Christianity in the region.

[Narikala Fortress]

The next monument we visited required physical stamina—we trudged up a steep hill (383m height), climbing hundreds of steps to reach the 4th century Narikala Fortress. The panoramic views melted away our fatigue—Tbilisi town and river Mtkvari on one side, the Japanese garden at the back and the domes of Abanotubani, a cluster of sulphur bathhouses to the side. Built by Vakhtang Gorgasali in orthodox style, the interior walls depict stories from the Bible.

[The sulphur bathhouse of Abanotubani]

Our next stop was the sulphur bathhouse of Abanotubani, to wash away any lingering fatigue. The water is harnessed from subterranean hot springs. In fact, Tbilisi gets its name from these hot sulphur springs—tbili means ‘warm’ in Georgian. The brick domes on the ground are the roofs of the bathhouse. One can choose from the ordinary to the exclusive chambers—the latter have nice blue tiles and modern decor. Both are clean and the service is efficient. It is said that Alexander Pushkin and Alexander Dumas bathed here.

Satire and Subversion

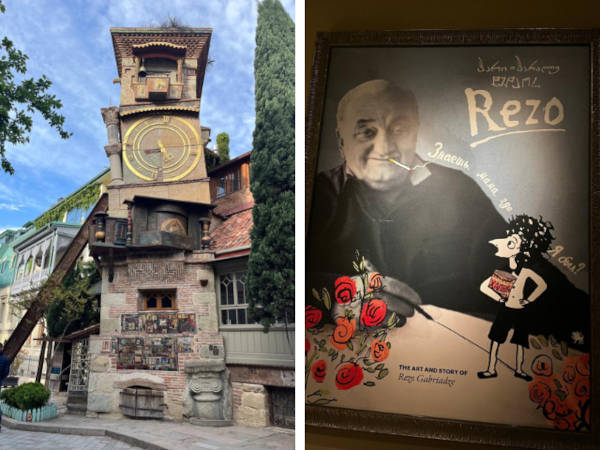

An hour later, fully refreshed, I am ready for the last stop, the Rezo Gabriadze Marionette Theatre, the first puppet theatre in Tbilisi (1981) and the most popular sight on Shavteli street in Old Town.

[From left: The Rezo Gabriadze Marionette Theatre; Rezo]

Rezo, as he is popularly known, is the most celebrated Georgian theatre and film director, playwright, painter, sculptor, actor and philosopher. The Soviet regime’s censorship made Rezo turn to the lesser known format of puppet theatre to avoid government attention, but he ended up attracting more attention. Even today, the shows are booked at least one month in advance. Those who couldn't book still flock to the cobbled patio to admire the tilted Clock-Tower designed by Rezo himself, where at the stroke of each hour a golden angel pops out of the painted balcony to ring the bell with a hammer.

This evening, Marshal de Fante’s Diamonds, a satirical gem written by Rezo, was on the cards. Of course I didn’t have a booking, but I managed to get a ticket—an extra chair in the aisle—through the kind favour of the director of the play.

The theatre is a small intimate performance space; the stage is specially designed for puppet theatre; subtitles in English and Russian are projected.

[Inside the puppet theatre: ornate balconies on either side for the auditorium]

For this play, Rezo picked a well-known folklore from the 19th century—at a wedding celebration a post master brings two telegrams from Paris for the impoverished General Vano Phantiashvili: news of the demise of the general’s uncle and the inheritance of the world’s largest diamond, Monte Rosa. The second telegram prompts the general to undertake a hasty trip to Paris. What follows are hilarious mis-adventures and intrigues, a difficult and unwilling lady-love, and a manipulative matchmaker who sets a trap to force the general to give up the claim to the diamond.

It is not difficult to catch the allegorical references to events closer home. The puppet characters bear the mannerisms of well-known political leaders.

After the show, we head for dinner. The Old Town smacks of different Asian flavours—Persian, Arabic and Central Asian.

Kakheti: Wine Country

There are options for several day trips out of Tbilisi. We take one that starts from the nearby Opera House on Rustaveli Street, has an English-speaking guide, and includes Kakheti vineyards, the Chronicle of Georgia monument and a visit to the charming walled town of Sighnaghi.

It is nice to be part of a small group of mixed nationalities—Russia, America, Turkey, India. Our affable guide regales us with interesting anecdotes about Georgian history and culture.

[The Chronicle of Georgia]

Our first stop is the Chronicle of Georgia on Keeni Hill to see the pre-historic grand narrative of Georgia captured in a monument.

First shock, on the hilltop the wind chill whips hard; second shock, about hundred steps to climb! But the scale and magnitude of the 30-40 metre tall pillars on a raised platform are awe inspiring. A cluster of 16 pillars, each with figures of kings, queens and heroes carved on the top half and stories from the life of Christ on the lower half. Just walking around and observing the agriculture, pottery making and brewing technology, and the grapevine cross depicted on the pillars feels good. At the back of the monument the Tbilisi sea, an artificial lake built around 1953, adds to the charm.

Next stop, the vineyards.

Our guide tells us about archaeological excavations as recent as 2008 that revealed that Georgia was ‘first’ in wine brewing and human civilisation. Archaeologists found grape presses and clay fermentation pots called karas and egg-shaped clay pots called qvevri about 50 km south of Tbilisi, dating back 6,100 years. That means the South Caucasus region may have been the birthplace of wine, not Western Europe which has only a 3,000-year-old history of winemaking. The discoveries included a well-preserved hand-stitched leather moccasin dating back to 3,500 BCE—indicating that Homo Erectus might have been living in Georgia since the Palaeolithic Era, the earliest hominins outside Africa.

[Vineyard by the roadside]

An hour-long drive through the countryside brings us to the vineyards, yet to come into full bloom. We stop at a couple of wine-tasting places; some also sell oven hot khachapuri to go with the wine; some have cellars where one could order something nice to eat. With so many flavours mixed up, it isn’t easy to decide on a preferred wine. The sommelier helps our group decide on the right wine.

So, there are about 500 varieties of grapes in the region and Georgia alone exported about 103 million litres of wine in 2022. Of course, most breweries use modern European methods, some still follow the qvevri vats—where grapes with skin and pip are buried in the ground for 6 months. No sugar, yeast or sulphites are added. The combination of grapes produces the difference in sweetness. I could gather some popular names and appellations of wines in this region:

-

Tsinandali wine - dry white

-

Mukuzani - dry red from Saperavi grapes

-

Kindzmarauli - dry and semi sweet Saperavi reds

-

Napareuli - whites and Saperavi reds.

After the tasting, we hit the road again. I asked our guide why Georgian wines are not so well-known. He explained that the islamic rulers didn’t allow wine making and so, Georgia had to restart the process.

We stopped at an old monastery on top of a cliff to visit St Nino’s church and catch the great view of the beautiful valley below. The countryside is dotted with monasteries and churches.

[The town of Sighnaghi]

We then headed to Georgia’s most beautiful walled town Sighnaghi that has an 18th century Defensive Wall around town, broad enough to walk on, and a museum of works by the famous painter Niko Pirosmani. To protect the town, vehicles are not allowed inside the town, so we walked on the cobbled street, enjoying the feel of the town with terracotta roofs, roadside stalls selling curios and other local artefacts. We stopped here for an hour for a late lunch at the Terrace Sighnaghi Restaurant.

Soon it was time to head back to Tbilisi and some more stories about Georgia from the tour guide who described his country as a peace-loving nation; a country with 240 days of sunshine; superior produce of tomatoes and aubergine, and the meat of Georgian sheep which is much in demand in neighbouring countries. As the trip came to an end, he dropped us at Freedom Square and recommended dinner at Bernard’s for an authentic Georgian meal.

‘Road to Russia’

[On the way to Stepantsmida]

The next day was for the most spectacular drive to Stepantsmida aka Kazbegi. From Tbilisi, about 150 km straight to the Greater Caucasus mountains near the Russian border in the north. It would be a three hour drive passing from verdant valleys to high mountains, to the base of the majestic snow-capped cone of Mount Kazbek, visible from afar.

This trip was not about visiting any important town on the way (there are none—even Stepantsmida is a sub-town) or monuments and monasteries. This was about an immersive experience into the pristine natural beauty of Georgia. The journey was the destination.

As soon as we left Tbilisi, we were into a pastoral landscape. The route is through Mtskheta, Ananuri and the tranquil Zhinvali reservoir—we took frequent breaks ‘stopping by the woods’ on this fine morning to admire, to soak in and reflect on God’s lovely landscape. This is the ‘promise…. (we have) to keep’.

A little further, we came across hundreds of trucks with international number plates, parked on the highway and realised that we had been driving on the historic Georgian Military Highway, almost following the footsteps of history—the route traversed by caravans and merchants long long ago. When Russians occupied Georgia, they used the ancient track to build this sturdy military highway popularly referred to as ‘Road to Russia’. It was used for moving troops during World Wars. These trucks from various countries were headed to the check-point at Larsi, a little ahead of Stepantsmida, to enter the mountain-tunnel for onward journey. There is no other way to cross the border except this tunnel. Georgia is still a transit country—it earns tax from the 3,000 trucks that pass through Georgia every day.

As we neared Gudauri village, we could see the snow capped peak of Mt Kazbeki (the dormant volcano) in the distance, the snow covered alpine meadows and the Gergeti Trinity Church perched on a cliff. This is the white wonderland loved by skiers.

[Gergeti Trinity Church, Gudauri]

We stopped for a nice warm Georgian lunch at Gudauri with smiling waiters dancing to country music. Loads of photographs later, we resumed the journey only to be stopped a couple of miles short of Stepantsmida. Heavy snow had blocked the road and there was no sign of it being cleared for a couple of days. Now I understood the reason behind the caravan of trucks. So near yet so far.

We headed back to the town of Borjomi, our next stop—a town known for Borjomi mineral water. Here we receive the mail about approval of the visa to Armenia for which we had applied two days back.

Armenia beckoned and we undertook the 10-hour cross country drive to reach Yerevan late at night. But that’s another story.

Toolkit: Why go to Georgia?

Besides all the reasons mentioned above:

-

Georgia is quite affordable in terms of fare, boarding and lodging. Bookings are available even last minute.

-

The scenic drive through Georgia is comparable to a drive through Europe.

-

Citizens of almost 100 countries can travel to Georgia visa-free. Others can apply on the e-visa portal at a surprisingly small fee.

-

Great for hiking and nature trails

-

It is a safe country. One can safely walk around even in the evenings.

Major towns

-

Tbilisi (capital town is a must visit)

-

Kutaisi (Monasteries)

-

Batumi (Black Sea coast)

-

Kakheti (wine region)

-

Borjomi (resort town known for the commercially bottled mineral water)

-

Svaneti (Alpine scenery)

When to go?

Spring and Summer are the best times to go. It can be quite hot in July and August but it is the best time to go to the Greater Caucasus mountains. Avoid winters.

May-June and September-October (late spring and early autumn) are shoulder months for going to Georgia.

Local travel

Most places are walkable. Tbilisi public transport cards are economical and can be used at Metro stations and buses. Ride Hailing apps like Bolt and Maxim are popular and cheaper than services in India and much cheaper than fares in European cities.

What to pack

Even in summer you need sufficient warm clothes and thermal inners, a wind cheater, an umbrella and walking shoes. It is a fairly conservative country, especially if you are visiting churches and monasteries.

Where to eat

It is safe to drink tap water in Georgia.

Staple dishes are Khachapuri, Khinkali (dumplings), Dolma (minced meat and spices wrapped in vine leaves) and Churchkhela (a popular snack of nuts strung on a thread and dipped in grape resin), Lavash.

An elaborate meal with drinks costs around $12-15 per head.

At Tbilisi, I recommend:

-

Pasanauri

-

Metekhi with dance Shadow performance

-

Megruli House for Georgian grilled meat

-

Bernard for Georgian meal

-

Republic for European food

-

Lumiere for ice cream

-

Keto & Kote

-

Machakhela (Khachapuri, near Meidan)