[Image by Steve Buissinne from Pixabay]

Good morning,

Last Friday, when Reserve Bank of India (RBI) governor Shaktikanta Das announced a review of the monetary policy, we were all ears. The pronouncement that India’s GDP will contract by 9.5% in FY 2021 has dominated all conversations since then. What kind of policies may follow in the months ahead? Is this the time for austerity? Or does the government spend?

We spent the weekend on Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea by Mark Blyth, professor of International Economics at Brown University. Allow us to reproduce some snippets from his book.

He submits that “Austerity doesn’t work. Period.”

Blyth has it that austerity follows a cycle. “Bailing led to debt. Debt led to crisis. Crisis led to austerity.”

He goes on to make the point that as a thumb rule, policy makers are attracted to adopting austerity because there is a history to it. “The discussion of the cases of austerity from the 1920s, especially the French case, shows us that austerity is generated in part by the inability of societies, as Barry Eichengreen first proposed, to agree on an equitable distribution of the tax burden. There is a strong parallel to be drawn between France in the 1920s and the condition of the crisis-shocked countries today. The alternative to cut is to tax. Given this, there are two other ways out of the crisis in addition to the usual choices of inflation, devaluation, endless austerity (deflation), and default.”

Therefore, he argues, in a follow-up in Time magazine, “Given then that cuts lead to more debt and less confidence, does it follow that we can have whatever level of debt and deficit we like with no consequences? Absolutely not… Countries that have successfully reduced debt have done so when others are expanding and their own economy is booming, which makes perfect sense.

“This is why austerity is a dangerous idea: it doesn’t work in the world that we actually inhabit. In the imaginary world of austerity, cuts always happen to someone else.”

Think about it.

In this issue

- Culture eats tech for breakfast

- The Biggest Bluff

- The new power marker

Culture eats tech for breakfast

In a conversation with Indian School of Business professor Bhagwan Chowdhry last Friday, former TRAI chairman RS Sharma spoke about some of the conflicts that emerged when people from the private sector worked closely with government bureaucrats during the Aadhaar project. Even calling someone by first name (a common practice in the private sector) instead of sir or madam (which is how bureaucrats expect their juniors to address them) became a source of discomfort.

The differences ran deeper than that, as RS Sharma writes in his recent book The Making of Aadhaar: World’s Largest Identity Platform.

Sharma writes that there was no doubt that it was a government project, and it’s government officers who would own it, take responsibility, and decide. “But this was not happening and there were some uneasy undercurrents.

“I was worried that those in other departments had started to look at this project as a private project driven by Nandan [Nilekani]. To make matters worse, in April 2011, a report in the magazine IEEE Spectrum also emphasized the theme of Indian expats driving this project, stating that as efficiency was not a strength with most government bureaucracies, Nandan had turned to Silicon Valley and a core group had worked as unpaid volunteers until Nandan's office prepared the paperwork to give the team official authority.”

Sharma was angry and complained to Nilekani about the articles “that made us look like a bunch of idiots who had no idea about the project until Silicon Valley showed us the way.” He thought Nilekani would defend it. Instead Nilekani sent a mail saying:

“I think we have a larger problem, which is that my original goal of integrating the best knowledge and skills from outside into the government on a sustainable basis has failed completely. We should discuss that sometime.”

Eventually they figured out how to work together. “The tensions that had initially threatened to derail the project were gradually diffused and over time the organization accepted this reality of coexistence of private- and public-sector people. In fact working together considerably improved the understanding among team members and we were largely able to have a good working environment.”

In The Aadhaar Effect, our colleagues Charles Assisi and NS Ramnath threw light on these tensions in the chapter The Hare and the Tortoise. Both, the private and the public sector, had their own strengths and weaknesses. The challenge was how would they cooperate and not compete. It holds several lessons for leaders.

However, many of the questions from the audience during the ISB event were around the old concerns around Aadhaar—does it violate privacy, is it safe, how does it work, etc. Sharma’s patience was evident during the conversation. He even acknowledged UIDAI could have done more to clear some of the misunderstandings about Aadhaar.

In 2018, we published a primer by Haresh Chawla—The thinking Indian’s guide to Aadhaar—which is still relevant, and much needed today. Do take a look.

Dig Deeper

The Biggest Bluff

The award-winning writer Maria Konnikova took a challenge upon herself—to learn how to play poker. Not only did she learn how to play, she went on to becoming the world champion in a year. How she went about it is something Konnikova has documented in her book The Biggest Bluff: How I Learned to Pay Attention, Take Control and Master the Odds.

While the book was published earlier this year in June, we haven’t read all of it. From whatever we have, Konnikova seems to have an incredibly compelling narrative in place and has us hooked to her story. The prelude places in perspective why she decided to learn the game—to understand the difference between skill and luck and to learn what she should control and what she must let go of.

Then there is this point when she is at the finals of the world championship. Instead of getting into the zone though, she starts to puke. That is when it occurs to her that in spite of having prepared for the event, you cannot bluff your way through chance.

We plan to spend time on the book this week after being reminded of it by an extract published in The Atlantic magazine.

“At the time, I was at sea in my personal life. It wasn’t an ideal moment to pursue an abstract question about a game I knew almost nothing about. My husband had been recently laid off, and a lot of our lives were in flux. But I quickly found myself consumed by poker. The game served as the perfect laboratory for my own questions about the role of luck in our lives. Poker isn’t the roulette wheel of pure chance, nor is it the chess of mathematical elegance and perfect information. Apart from the underlying mathematics, poker depends on the nuanced reading of human intention, interactions, and deceptions. It gives you parameters that are just clean enough to allow you to grapple with that uncertainty.”

Dig Deeper

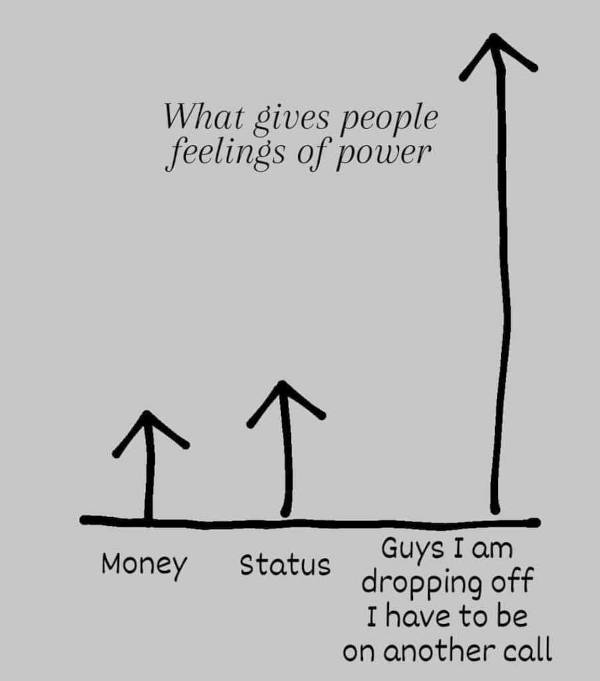

The new power marker

(Via WhatsApp)

Does this sound familiar? Are there people around you who do this regularly? Is this part of a new normal? Let us know.

And if you missed previous editions of this newsletter, they’re all archived here.

Bookmark Founding Fuel’s special section on Thriving in Volatile Times. All our stories on how individuals and businesses are responding to the pandemic until now are posted there.

Warm regards,

Team Founding Fuel