[At Point Arkwright on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast, two great ocean currents—one warm, one cool—meet to create a zone where new life thrives. It’s a quiet collision that mirrors the rhythm of all journeys: movement finding stillness.]

Bill Bryson once wrote that “nothing about Australia is small.” He was right—not its skies, not its humour, and certainly not its silences. Even the quietest of places here seems to hum with generous vastness.

Australia first entered my imagination through cricket—through Richie Benaud’s calm voice describing fields impossibly green and summers that never ended. Years later, Bryson’s Down Under gave the country a personality: dry, irreverent and endlessly curious. I read it long ago, yet his words return every time I land here.

The Search for Parking and Serendipity

One bright Sunday morning, we found Point Arkwright by accident—after giving up on parking at Coolum Beach on the Sunshine Coast. We circled the streets like clumsy midfielders chasing a ball that kept slipping away, then drove further north. What began as a mundane hunt for a parking spot turned into a morning I will remember for a long time.

Point Arkwright juts into the ocean like an elbow of land refusing to stay still. The waves rush in, the cliffs lean forward, and the sea argues timelessly with the rocks. A board at the entrance warned of strong currents and slippery stones, but the path ahead felt more like an invitation than a warning.

The Wooden Railing and the Whale Watchers

[At the entrance to Point Arkwright, the sign warns of strong currents and slippery rocks—a reminder that even beauty comes with boundaries.]

At the edge stood a simple wooden railing overlooking the rocks. I ran my hand along it without much thought, not realising it would become my perch for the next few hours. Around me, a small crowd had gathered, binoculars in hand—whale watchers. I joined them.

It was migration season, when humpback whales travel thousands of kilometres from the freezing Antarctic to the warm waters of Queensland to give birth before heading home again. Mothers and calves. Giants and gentleness.

On an earlier visit to Stradbroke Island, I had seen a board where volunteers marked the season’s whale count in chalk—a living scoreboard of one of Earth’s great annual journeys. I had thought then, and again now, how few of us pause to notice that movement back and forth is not failure. It is nature’s rhythm.

[In Stradbroke Island, a running chalkboard keeps tabs of the season’s humpback whale sightings—3,961 and counting. Proof that life, too, keeps returning.]

At Arkwright, you could sense that same pilgrimage unfolding—first far away, then closer. A man beside me launched a two-thousand-dollar drone that, he said, could travel twelve kilometres out to sea. On his remote screen, which he generously shared, I saw what my eyes could not: a mother and calf gliding side by side. The mother’s tail flapped like a flag of joy. There was a grace to their movement that made us all fall silent. No music. No narration. Just awe.

The Everyday Beauty of Shore and Memory

I turned away for a moment, needing a break from all that beauty. On shore, life carried on in its easy Australian way. A couple of surfers jogged past—all muscle, tan and sunshine. Where, I wondered, do all the beer bellies go? A Westpac rescue chopper buzzed overhead, a polite reminder that good looks do not replace good sense. The scene could have wandered out of Baywatch and decided to stay.

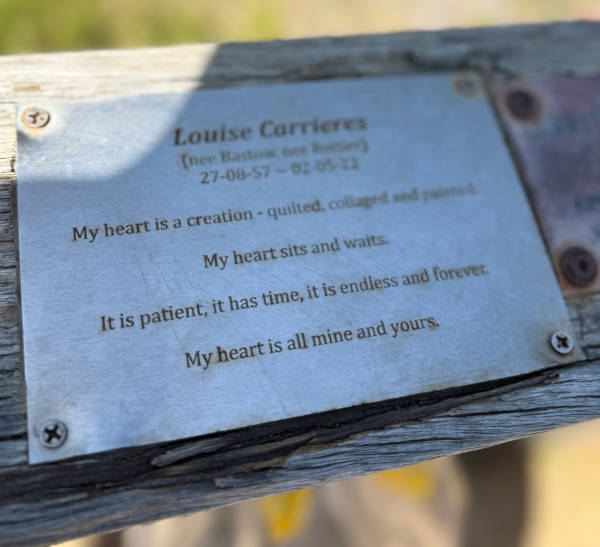

Leaning on the railing, I noticed what looked like a bunch of fresh flowers near my leg. When I looked closer, I realised they sat below small metal plaques affixed to the fence—quiet memorials for people whose lives had somehow found a home here.

One plaque read:

My heart is a creation, quilted, collaged and painted…

It is patient, it has time, it is endless and forever…

[Along the wooden railing overlooking the sea, small metal plaques remember lives that found a home here. Between the yellow flowers and the salt air, memory and tide keep their own conversation.]

The small bouquet of yellow flowers seemed to wait in stoic silence, as if for the sea to notice—or for the whales to carry her story to the frozen south. Who wouldn’t want to know more about a quilted, collaged and painted heart waiting forever?

For a while, I stood in silence as the waves crashed into the rocks. A rhythm so musical it seemed like magic.

A Wedding Under a Pandanus Tree

[Under a pandanus tree, two older lovers said their vows—five friends, a picnic rug, and the ocean for an audience. Joy, in its quietest form.]

A few metres away, laughter broke the stillness. Under the shade of a pandanus tree, two older people were getting married. Five guests stood around a picnic rug, a bottle of wine beside a cooler box, the sea as their backdrop and the sun as their spotlight.

There were no musicians, no aisle, no crowd. Only the rustle of leaves, the whisper of waves and the occasional gull passing by. It was simple and beautiful, almost private enough to miss if you weren’t paying attention—the kind of wedding where joy and hope don’t announce themselves. They just stay.

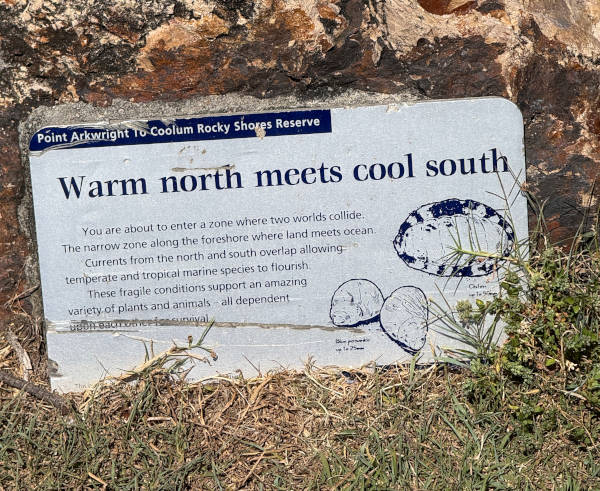

Even the land seemed to understand. A sign on a nearby rock read Warm north meets cool south. It explained how two great ocean currents, one tropical and one temperate, meet here to create a zone where new life thrives. That overlap, that handshake of opposites, is perhaps what gives Point Arkwright its quiet magic.

[Warm north meets cool south. At this rocky headland on Queensland Sunshine Coast, two great oceans meet—proof that opposites , too, can create life.]

I stooped to pick a few shells from the sand, delicate spirals shaped by centuries of time and tide. Perfect enough for an art gallery, but here they lay scattered and ignored. Maybe that is the Australian way too—to not make a fuss about beauty.

Of a Prime Minister and the Endless Tide

[Two surfers wade into the surf at Coolum beach, chasing the same waves that have shaped these shores for centuries—proof that play, too, can be a kind of prayer.]

As we packed up to leave, I looked back at the sea. Hours had evaporated. The whales were still out there, moving with unhurried certainty, following instincts older than maps. They do not rush, do not post, do not compare. They just travel, turn and return, carrying entire oceans in their memory.

I stood there for a long while, watching them disappear and reappear—as if the ocean itself were breathing.

As I watched the tide twist and turn, I recalled a story Bryson had written in Down Under. He noted, with his trademark understatement, that “it takes a certain genius to lose a Prime Minister, and it is the only country to have managed it,” referring to Harold Holt, who went for a swim one morning and never came back. Most agree it was a tragic drowning, though theories of shark attacks and secret Chinese submarines floated for years.

In true Australian fashion, Holt’s memory lives on in the most ironic of tributes: the Harold Holt Memorial Swimming Centre. Only Australia, I thought, could honour a drowned Prime Minister by naming a pool after him. That mix of mystery, mischief and matter-of-fact acceptance seems to sum up the Australian spirit perfectly.

Standing at Point Arkwright that bright Sunday morning, it felt clear that travel isn’t always about going places. Sometimes it’s about standing still long enough for movement to find you—watching whales return home, hearing warm and cool currents meet, realising that everything, from love and loss to laughter and migration, is connected by the same tide.

The endless tide that turns without reason, yet with purpose only it knows.