[By kai Stachowiak under Creative Commons]

I am no connoisseur of art. Neither do I understand the nuances of it. That out of the way, pause for a while and take a look at this painting.

[This image is a faithful digitalisation of Blue Poles (original title: Number 11, 1952), an abstract painting from 1952 by the American artist Jackson Pollock. Source, Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=35971938]

When I was first introduced to it by way of an anecdote by Roman Krznaric, a thinker and philosopher, in his lovely book How to Find Fulfilling Work, it made no sense to me—until he placed it in context.

Blue Poles, as this painting is called, was created by Jackson Pollock in 1952. When he was 23, Krznaric’s father asked him what he could see in there. After both of them stared at it for a while, the father concluded he was looking into a prison cell. Krznaric felt just the opposite—that he was trapped in a cell, looking out in frustration at the new world.

Go back to it. What do you see now? Are you inside a prison? Are you outside of it? There are no right or wrong answers.

When I look at it intently, I see the bars of a prison in which I am trapped and want to get out of.

“But how could you possibly feel that?” Krznaric’s father asked him. “You have so much freedom and so much opportunities before you.” I looked harder. But all I could see were the bars of a prison cell inside which I am.

That both of them saw two different things, Krznaric concluded, is because they come from different worlds. His father shifted to Australia as a refugee from Poland. Though a talented mathematician, linguist and musician, he finally settled in as an accountant at IBM in his adopted country. The job offered him the security and stability he so desperately needed.

The young Krznaric, now an Australian citizen, was faced with a multitude of choices. When I extrapolate myself to where Krznaric found himself, I see what the issue at hand is.

My paternal grandfather and his brother were from Cochin (now Kochi). The dominant occupation in those days was seafaring, which is what both of them got into. My maternal grandfather was a coffee bean merchant because in Kannur, the part of Kerala he originally hailed from, that was, historically, the business of choice—until, like many Syrian Christians, he migrated to Thrissur to set up shop.

When my dad and his brothers grew up, their choices expanded. Indians who came of age in the late 1950s craved security. The Indian Air Force sounded like a good option. He grabbed the first opportunity that came his way, got posted to Shillong and off he was to a secure life.

My maternal grandparents thought of him as good a settled boy as any for their daughter who had just about turned 20. Some years later, my dad was last posted in Mumbai and opted for voluntary retirement, and my brother and I grew up in the city for most of our lives.

As compared to our grandparents and parents, my brother and I had more to choose from in the 1990s. I studied biosciences at St Xavier’s College in Mumbai, while my brother took to physics at the same place. But the media was opening up as well. Advertising, journalism, television, all of these seemed like exciting options. So, even as I took up a distance course in economics, I enrolled for a course in journalism too. Career choices were aplenty.

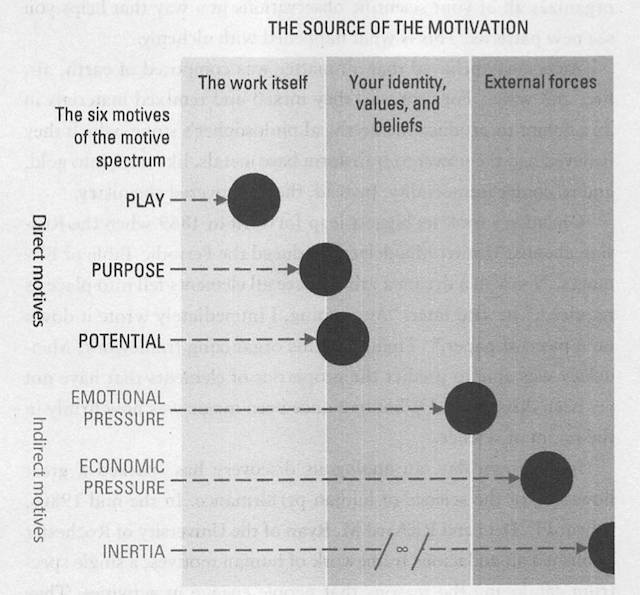

But as this chart below illustrates, there were indirect external forces at work on me: economic and emotional. India was in transition. The family needed money and society insisted I was no longer a boy, but a man, and implicitly insisted I take a call and get into the workforce.

[Source: Primed to Perform by Neel Doshi & Lindsay McGregor]

There were a few options before me. My biosciences background could take me to a pharma company, while my media and economics courses could get me a place at a newspaper or magazine. Media sounded more appealing and business journalism it was.

In hindsight, I don’t know where the 20-odd years spent in journalism went. All I know is that I loved every minute of it. But as I have articulated so often in the past in this series, circumstances conspired, and I got to a point where I finally had to confront my direct motives.

I’m in my early 40s now and a few questions stared me in the face four years ago:

Question 1: Am I living life to its fullest potential by continuing as a journalist?

Question 2: What is the purpose of my career?

Question 3: If I am enjoying every minute of journalism, and it is indeed play for me, why do I feel stressed out?

Some thought later, answers emerged.

Answer 1: No, I am not living to my full potential.

Answer 2: I didn’t deliberate much. I was too young when I got into it. There were indirect motives at play. The purpose fell into place later. But it is now ready to be scrutinised.

Answer 3: I don’t know.

Follow-up question 1: Is this what they call a mid-life crisis?

Answer: No. I need to find meaning and fulfilment.

Follow-up question 2: What is holding you back?

Answer: Only two things—money and inertia.

Krznaric makes a few arguments on why inertia kicks in. The first is that the kind of world we live in now is an abundant one. “Abundance of options becomes an overload. At this point, it no longer liberates, it debilitates,” he writes.

Let me give you one instance.

On the back of credit card points that I have accumulated, I am sitting on thousands of rupees’ worth of gift vouchers from Amazon, and various other department stores. My wish list of books on Amazon is long and the number of coupons I have can buy all of these and leave room for more. But I don’t know where to begin.

An optimal solution would be to impose restrictions on the choices I make, and go about implementing them clinically. But when it comes to making a career choice, what am I to do? There are a whole lot of things I want to try before I die. So what is holding me back?

I’m staring at two kinds of regrets.

1. The first is the sunk cost fallacy. There is this part of me arguing with myself to say, “What about all these years you have spent on the job? You know what to do and how to do it. Are you sure you want to write it off by heading out into unchartered territory?” If I fall for the question, it is entirely possible I may get bored a few years down the line.

2. Then there is the potential regret I may feel if didn’t live a life true to myself and not give all of what I wanted to a shot.

Assuming I decide to ignore these questions, there is money to be dealt with. The tension between money and meaning isn’t an easy one to negotiate.

So, I finally took a call, it is better to try than to die without having tried. With a few close friends, I started Founding Fuel Publishing. The venture is just a little over two years old now. It took close to two years of work to get it off the ground. Even as I was getting into it, I knew that all of us would have to take serious pay cuts. The lifestyle I was used to would have to give way to a more frugal existence.

One of the lessons I have learnt, though, is life has its own way of adjusting to the monies on hand. The more money you have, the more your wants. The less you have, the fewer your wants. The real call to take is: “What do you need” versus “What do you want”.

When I whittle the list down, what I really need in material terms is actually little. Making a transition to simpler living requires embracing Picasso’s philosophy: Art is the elimination of the unnecessary. What I really want is meaning and purpose.

In trying to find meaning and purpose, I made a few interesting discoveries that weren’t evident to me until I read Krznaric.

Discovery 1: I have multiple selves.

I couldn’t figure out why my wife has to devote as much time as she does to teach underprivileged children who cannot afford expensive tuition fees, serve the community through her church, participate in social events and help organise community festivals.

I can do only one thing at a time. Everything else be damned. When thought through, there is nothing wrong in either her position or mine. She is what Krznaric calls a “renaissance generalist” and I am a “serial specialist”. To find meaning, it is important that you take a call on what you really are. In her case, width matters.

That is why when I showed her the painting illustrated above, she thought she was outside a prison cell. When I presented it to my 11-year-old daughter Nayantara, she didn’t feel imprisoned either.

Unlike my wife, for whom width in interests matters, depth matters more to me. What is similar though is that over time, their meanings for both of us. The challenge is to identify when those changes occur and know how to make the transition.

So, in making career choices, what mattered to us at 16 is very different from what mattered to us in our 20s and so on. My exigencies have changed and so have my interests. There is this part of me that was interested in a pure play media business. That is why I stayed as long as I did in the media.

My affair with it continues and writing these pieces for Mint on Sunday gives me enormous joy. But there is this part of me that wants to do other things as well. I cannot do that if I am wedded to a business.

I will regret it if I didn’t give entrepreneurship and my dreams a chance. It compels me to unlearn all of what I have learnt, my limits are stretched, and suddenly I find new purpose.

Does this mean I see myself as wedded to Founding Fuel forever? It is entirely possible that I will transition at some point to being a medical doctor. I love how surgeons work. And what is to stop me from attempting to be one and learn new skills? I have at least another 40 years of life left in me. Who knows what else may catch my fascination?

Discovery 2: It’s not the money alone.

Take a good look at this chart here. For this essay, I have used Google Trends to chart three kinds of people that all of us in India watch closely.

• The blue line corresponds to Mukesh Ambani, the richest man in India and among the richest in the world.

• The red line tracks the trajectory of Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India. Beginning around 2012, people started to get more interested in him than in Ambani, who is much richer than Modi.

• Curiously, the yellow line corresponds to that of cricket Virat Kohli. While Ambani is richer and Modi the most powerful man in India, both have, with brief interludes for Modi, given way to Kohli. Kohli's popularity over Indian hearts is unbeatable.

• The only character who can compete with Kohli is a fictional creature that exists only in comic books and television for children called Doraemon and is represented by the green line.

How do you explain this? Accept that a fictional character whom most adults dismiss and an apparently silly, temperamental cricketer appeal to the heart of more Indians than the wealthiest and the most powerful. Whether or not people realise it, in their minds they listen to the heart harder, however loud the head may scream.

Discovery 3: Start with “Why”.

With Founding Fuel, one question everybody asks me is, when will you start to earn big money? My co-founders and I come from a world view that we ought to start someplace. That someplace lies in asking ourselves a tough question: Why are we doing what we are doing?

Author Simon Sinek’s hypothesis is that everybody begins by doing “What” they do, then asking “How” can they do it best and, when reality sinks in, finally asking “Why” are they doing it.

But if we were to reverse the process, getting the WHY absolutely right is pertinent. HOW you do it is then a tool and WHAT you do is the outcome. This is not to dismiss the significance of money, because money brings advantages. But money is not the intended outcome. There is a larger purpose at stake here.

Krznaric signs off his lovely book by pointing to the conversation between the protagonists in Zorba the Greek:

“There is one last way to break with your past and begin a new stage of your career journey, which is to take some advice that appears at the end of the 1964 film Zorba the Greek. Zorba, the great lover of life is sitting on the beach with the repressed and bookish Basil, an Englishman who has come to a tiny Greek island with the hope of setting up a small business.

“The elaborate cable system that Zorba has designed and built for Basil to bring logs down the mountainside has just collapsed on its very first trial. Their whole entrepreneurial venture is in complete ruins, a failure before it has even begun. And that is the moment when Zorba unveils his philosophy of life to Basil:

Zorba: Damn it boss, I like you too much not to say it. You have got everything except one thing: madness! A man needs a little madness, or else...

Basil: Or else?

Zorba: ...he never dares cut the rope and be free.”

[This is a mildly modified version of an article first published in Mint on Sunday under the slug Life Hacks, a column that appears every Sunday. This has been reproduced with permission.]