[Image by Damon Nofar from Pixabay]

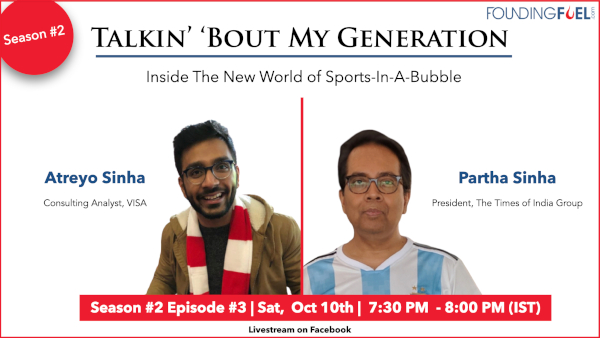

By Atreyo Sinha & Partha Sinha

As an opinionated duo, my father and I have never had a shortage of topics to discuss. Whether it’s at breakfast debating politics, at dinner after a movie digging up plot holes, or just generally annoying my mother, quick wit and constant jabber form the backbone of this family’s identity. And somewhere in all that constant banter, there is a distinctly Indian male characteristic that brings us together—an immense, often problematic reverence for sport.

You see, neither Sinha is particularly athletic (although my dad will likely cite a footballing injury that nipped a promising goalscoring career in the bud), or even outdoorsy, for that matter—but our armchair fandom begins with cricket and football, and continues into tennis, F1, basketball, golf, and pretty much anything else that can be classified as a sport. With the Indian cricket team and Arsenal Football Club however, that fandom may be a bit more devotional.

For years, sport was the thing that brought us together every weekend: an excuse to watch Arsenal, have a drink, and get invested in a series of events way out of our control. I’ve lived away from home for over seven years now, so often those catch-ups were long FaceTime calls and live texts discussing the game. So when the pandemic struck and almost all sports were suspended, we were left with a void that we weren’t sure how we would fill.

Like any other facet of life, the pandemic has made us (just like all fans) rethink our relationship with sports. What it has also done, is reinforce some of the fundamental differences between the two generations. For my father and his friends, watching cricket always meant a trip to Eden Gardens. As TVs became more commonplace, some traded their tickets for brand new screens, but the core idea never changed: you watch the game at the local ground. On the other hand, as much as I love a stadium visit, watching sports remains a TV activity at its core for me. In fact, when I’m not watching a game on TV, I’m playing FIFA or NBA 2k—so when sports returned on TV with empty stadiums and simulated crowd noises, I wasn’t particularly bothered. But for my dad, and many his age, the game is an epic battle in an arena. He finds the new iteration of the game unwatchable, and his discomfort is echoed by several commentators who claim their work is that much harder without a crowd’s emotions to draw from.

But as sports gradually returned in different ways and forms, we were confronted very directly by an unavoidable reality. The reality that sport may just be a spectacle, as Russell Brand, a West Ham fan, puts it, “meant to keep us entertained and distract us from the real issues out there”. On the one hand, it’s now a level playing field. There was always a hierarchy of fandom: fans who went to the stadium and followed the game in a community environment sneered at those social media/armchair impostors who watched and supported through screens. That hierarchy has been challenged, and fandom has been democratised. But on the other hand, the pandemic has exposed our lopsided priorities as a society. We prioritise based on class, utility, and profit—audiences all over the world are watching multi-millionaire athletes play full contact sports, but are being told to avoid hugging their grandmothers. Bizarre as the comparison may seem, Covid-19 has merely uncovered stratifications that existed well before our mask and hand sanitiser days.

Take for example some of the numbers involved. The IPL’s 2020 edition kicked off in the UAE recently, and it is being played instead of the T20 World Cup which was meant to be hosted by Australia at around this time of year. One would think that the World Cup, an international affair—in a perfect year like 2020—might take precedence. But of course, the Rs 4,000 crore ($600 million) IPL was the event that all parties decided would be the best to conduct, the same way that the bilateral India-Australia series will be taking place ahead of the T20 World Cup as it is estimated to net about $300 million for Cricket Australia.

But will these tournaments be the same without fans? Of course not. And yet, somehow, the return of these sporting spectacles brings a certain sense of normalcy into the Sinha household. For all his opposition to simulated crowd noises and empty stadiums, my dad is sure to tune into every single game, while I start reading the newspaper back page first.

When the pandemic hit, my dad and I were both in the midst of huge career changes. I was wrapping up my final semester at graduate school looking for a job, while my dad was starting a new role in a fairly new industry—he was moving from advertising (he had quit McCann) to a media house (Times Group). My interviews, originally lined up to be in person, were all rescheduled and reorganised to be over Zoom, while my dad’s first day meeting his entire team was a series of back-to-back-to-back video calls. Add to this the general sense of uncertainty and anxiety from being quarantined at home, and we absolutely needed something to relieve all that stress. Except the only problem was that all sports, with the exception of a few Ukrainian volleyball and Russian table tennis games, were cancelled. Trust me when I say neither my dad nor I have watched as many old highlight tapes on YouTube as we did for those two months. At that point, Lionel Messi GOAT Skills CRAZY Dribbling | Despacito 4K 1080p was a way of life.

When we got the news that the Premier League was going to restart in mid-June, we were elated. Soon after, that elation turned into dread when we learned that the first game back would be against the defending champions, Manchester City, at their home ground. The game was a disaster—Arsenal lost two key players to injuries in the first half hour, and the substitute defender conceded two goals and saw a red card within 20 minutes of coming on. But even then, we were happy to have football back in our lives. My dad said, and I quote, “Premier League stress is a good counter for Covid stress”.

Despite the small glimmers of good news, the opinionated Bengalis in us couldn’t help but look right into something that sport was making very obvious: the idea of Covid privilege. In some ways, this is where the generation gap or difference in sensibilities didn’t quite matter. Even within elite athletes, most of whom are handsomely paid and more than comfortable, there were some players who could ‘afford’ to sit out, while others had to utilise what could be turning points in their relatively short careers. Many NBA and baseball players in the US decided to sit out the season restarts. Gene Orza, former chief operating officer for the Major League Baseball Players Association, pointed out that if you’re a player who has made $30 million in the last three years versus another player who has debt coming out of his ears and needs to capitalise on this opportunity, the decisions are being made from very different places.

And once again, via the pandemic, the maxim ‘life imitates sport’ rings undeniably true. One of the biggest reasons my dad and I are such big fans of sports and people who play or watch them, is because teachings from sport will undoubtedly trickle into other aspects of life. While data on one hand consistently shows that Black Americans and other minorities suffer disproportionately from the virus, the rising numbers at home in India remind us that ‘social distancing’ is not a plausible solution for many impoverished communities.

So, while sports can be a fun, light topic for the boys in the house to banter over, it can also serve as a solemn reminder of the harsh realities faced by millions everyday. And like most other things in our daily lives, the commercialisation and profiteering off of sports—originally meant to bring together people despite income, race, class, or colour—is a reminder that few things will be left pristine if they have monetary potential. Perhaps that is what my dad really dislikes: behind his aversion to simulated crowds, there is a deeper sense of the beautiful game slipping away from the hands of the common person. Across most of the world’s top sporting leagues, local fans are already priced out of stands on a consistent basis, youth players routinely get replaced by mercenaries with no connection to the locals, and now it seems that maybe, just maybe the fans are expendable too.

As for me, however, the story is a little different. I was born into a world where sport was already commercialised. I grew up in a suburb of Mumbai where my classmates supported teams from Newcastle, Valencia, and Los Angeles. In many ways, the televising of sports led to their global appeal, and my generation was right in the line of fire. We benefited from the upsides of profit-oriented sports: we could support both our local teams and teams thousands of miles away all at once.

This is to say that it’s not all bleak: just as Covid has unearthed some of the darker realities of sport, it has also paved the way for an incredible amount of innovation. The IPL and the NBA have already shown that creating a ‘bubble’ with high-frequency and high-volume testing and isolation can basically flatline the virus’ spread. On the field, too, innovations have been aplenty. Borussia Monchengladbach’s supporters filled their stands with cutouts, while fans all over the world have been tuning in via large video conference courtside and pitchside screens to be as present as they can at the real venue. The NFL is partnering with Oakley to design a helmet-mask hybrid for their games, and multiple sports authorities have been working on rings, bracelets, and other devices that can monitor player health round the clock.

Despite my earlier grim prognostications, it is evident that there can be a silver lining to most difficult situations, and sports is indubitably a prime example of that. After all, as a pair of lifelong Arsenal supporters, delusional optimism is a necessity, and a way of life. And I’m optimistic that while fans will soon be allowed back into stadiums, some of the lessons from the pandemic will have seeped into sports, for the players, the organisers, and the fans alike. Safer, cleaner stands will hopefully be complemented by greater accessibility in sports broadcasting; greater off-field fan engagement will hopefully be coupled with better health protocols for players and staff; affordable ticket prices will hopefully be paired with less schedule congestion. Athletes will hopefully realise the impact they have and continue to advocate for social change, and ultimately, hopefully dad will come around on this new-age stuff, too.

Of course he will. We love sports way too much.

Partha Sinha: Inside the new world of sports-in-a-bubble

Partha Sinha points to some fundamental differences in how his and his son Atreyo’s generation relate to sports.

1. “Play for us, was an outdoor activity; play for them was a button on the console,” he says.

His generation got drawn to sports by playing in the ground—and then it moved to going to the ground to support the neighbourhood or school team, and then the clubs and the national teams.

But for his son's generation, their entry into sport started with TV and moved on to PlayStation.

What was given was that “Sports needed to be real,” he says. “The narrative of sports gave us heroes. Skills, power, perseverance won. The drama of sports was written with values that were close to our heart.”

2. “Simulation was like cheating. But they're comfortable with the idea of simulation in sports,” he says.

His generation was outside the arena, and was never in control of the game. Whereas they love controlling as much of the narrative as possible—they play in managerial mode in FIFA.

That said, with Covid, now that live sport disappeared, there’s a void.

And simulation has become a part of the game.

“The game started happening in an empty stand. And that empty stand brought in the legitimacy of simulation. This is where our two generations need to reconcile—the idea of fake being a part of sports narrative.”

So will sports change?

Not dramatically, he says. Instead of drawing from spectators, players will now draw from each other.

And it will accentuate the idea of a "Covid bubble”. Where “those who matter—the players and those on the bench—are Covid tested and are playing contact sport. Everyone else—like fans, who actually don't matter—are advised not to get out of the house.”

But the truth is, that's happening everywhere. “Covid was supposedly the ultimate form of democratisation. But we don't know how to live without hierarchy. So we created hierarchy very quickly—a Covid bubble in sports as well as in life.”

Join Partha and Atreyo as the two fans compare notes on the many ways they see the game changing.

If you haven’t registered to watch the show already, register here: https://bit.ly/FFTAMG

In the meantime, here’s a playlist of Season 1, E01-07.

Bookmark the series. (The show is supported by a column on Founding Fuel, and an ongoing conversation with the Founding Fuel community on our Slack channel.)

Still Curious?

- Read: Who took away my film? Where Damodar and Harsh Mall debate what entertainment will look like post-pandemic.

- Read: Fantasy sports & future of sports. In this edition of This Week in Disruptive Tech, NS Ramnath tells you why you should care about Dream Sports' recent fundraise.