[Image by linushajan from Pixabay]

Welcome to the first edition of The Growth Factor Weekly (TGF Weekly). The newsletter will explore some of the biggest questions around small businesses through the stories of MSME owners, bankers, investors, customers, employees and technologists. It will reach your inbox every Saturday at 9:30 AM IST.

It will be curated by Founding Fuel’s senior writer NS Ramnath, who is researching industrial clusters in Tamil Nadu on a Bharat Inclusion Fellowship 2020. Bharat Inclusion Fellowship, an initiative of CIIE.CO of IIM, Ahmedabad, is aimed at addressing the knowledge gaps that prevent entrepreneurs from developing effective solutions for the underserved. TGF Weekly will share insights from the research as it progresses.

The newsletter is a part of the conversation we will have with our community—on our website, over video conferences, webinars and a Discourse platform we are setting up. We will keep you posted.

Please do share this newsletter with friends and colleagues who might be interested in this theme. Thanks for being a part of what promises to be an incredible journey of learning and insights.

The systems view | The curious case of an unused LPG cylinder

Earlier this week we had a fascinating conversation with Puneet Gupta, co-founder of Kaleidofin, a platform that helps customers choose the right mix of financial solutions from a variety of providers. Gupta, an MBA from IRMA, was a part of the microfinance team at ICICI Bank, and a co-founder of IFMR Group before he started Kaleidofin with Sucharita Mukherjee in 2018.

Gupta shared an encounter with a lady in Bihar that had a huge influence on how he looked at the problem of financial services. He and his team members were on the field in Bihar trying to understand how people used cooking gas, how often they used the LPG, how many times they got a new cylinder in a year, etc. It’s an important question because as Gupta explained, it was a good predictor of the income and wealth of a family. Then they came across a woman who said she had a cylinder but never used it.

“I could not relate to it, because in my house it’s a natural disaster if we ran out of cooking gas,” Gupta said. So, he asked her for more details, and found two reasons why she left it untouched.

- All her utensils were bought for use on a traditional chulha (clay stove). They didn’t work on the cooking gas stove. If she were to use LPG, she would have to upgrade her entire cookware.

- Cooking on a chulha aligned well with her schedule. Her husband is a migrant worker and her kids go to school. The moment she's done with her morning chores, she has to go to the field to work before it gets too hot. But, before she leaves home, she puts rice and adds just enough firewood to the chulha. By the time she comes back, the firewood has burnt itself out and the rice is ready. While rice might take less time to cook, on an LPG stove she has to supervise that, and that did not go well with her daily schedule.

Gupta said, he sensed that she would eventually see the advantage of LPG and figure out a way to adjust her lifestyle to fit that in, but right at that time, an LPG cylinder was not relevant for her.

[Image: Kaleidofin]

Her goal was not an LPG cylinder; her goal was to get multiple things done—send off children to school, earn a living from her work in the fields, and also get the cooking done. Cooking gas is a useful technology, but sometimes, it could end up being a light bulb in a house which didn’t have a power connection.

Finance has exactly the same issue, Gupta said. “Most people have built systems whereby they run their finances, taking into account social agreements that people have with each other. People self-insure themselves.”

Observations such as these from the ground shaped how Kaleidofin built its own value proposition. It placed primary emphasis on the life goals of its customers—for example, a child’s education, expanding a kirana store—and in helping them achieve their goals through finance.

Dept. of unintended consequences | When going debt-free comes back to bite you

[Image by Dewald Van Rensburg from Pixabay]

Abhishek Dhingra is an MBA from The Asian Institute of Management, Manila and runs Mr Pronto, a chain of shoe and bag repair shops. “B-schools teach you that debt is good because it helps you grow. But when you own your business, and when your cash flow is good, you want to reduce the debt,” he said.

That’s what Dhingra started doing as his chain stabilised after reaching 15 outlets. He was on his way to becoming debt-free.

And then, COVID-19 struck. Revenues went down to zero. But he had to pay rents and salaries, so expenses remained the same. He went to his bankers, and they said, “Under the COVID scheme we can give you 20% of your outstanding loan.”

Only, his outstanding loan had now come down to Rs 6 lakh, which meant he would be getting about Rs 1.2 lakh as additional loan. “It’s a joke when you consider my requirements are Rs 10-12 lakh,” he said.

This is the problem with using a single criterion (which is, existing loans) to extend support during a pandemic. It does not help at all, he said.

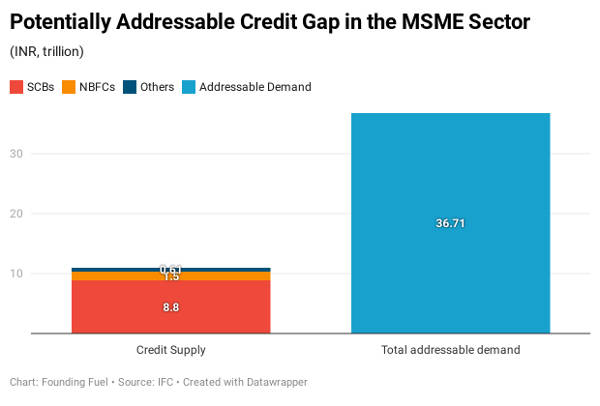

Chart of the week | Who will fund the MSMEs?

A report by IFC two years ago estimated the total addressable credit demand from MSMEs at Rs 37 trillion, 3.4 times more than the credit available.

Click here for an interactive chart

Most of the formal credit to MSMEs comes from public sector banks, but by another count, MSMEs get only 15% of their credit requirement from formal credit. For the rest, they depend on their own network.

The big question is how will things play out during the pandemic? Will the informal sources provide enough for the majority of MSMEs to recover and go on? In a conversation with Founding Fuel recently, Manish Sabharwal, chairman of Teamlease, and a Reserve Bank of India board member said, it’s “unmodellable”.

Here’s a more detailed answer from Sabharwal:

“In India, SIDBI and others cover a very small proportion of total MSMEs. I think MSMEs are also more resilient because they also don't really have traditional sources of financing. Everything that is a bug for low productivity is a feature for low resilience.

“When I think of India from a productivity perspective, we have a different trajectory. But in this pandemic MSMEs are more resilient, farm employment is more resilient, self-employment is more resilient. And that's why the economic shock of the pandemic may get absorbed and that's why I think we will get back to normalcy much earlier. Fifty percent of India is self-employed and 45% works in agriculture. And that is the shock absorber.

“Of the 63 million enterprises, less than one million have formal bank credit. So it's not likely that the 62 million will suddenly be given bank credit in an emergency. The biggest lesson for me in this pandemic is that economies don't do things in emergencies that they can't do in peacetime. You can't ask an economy to do something in an emergency that they can't do in peacetime.

“So, we should be more outraged in peacetime and less outraged in wartime, we should be more upset about the lack of labour reform in peacetime than we should be outraged about job creation now.

“Only one million out of 63 million MSMEs have formal credit anyway and they will get some form of help. But, will the 62 million figure out from informal sources how to manage it? It’s unmodellable.”