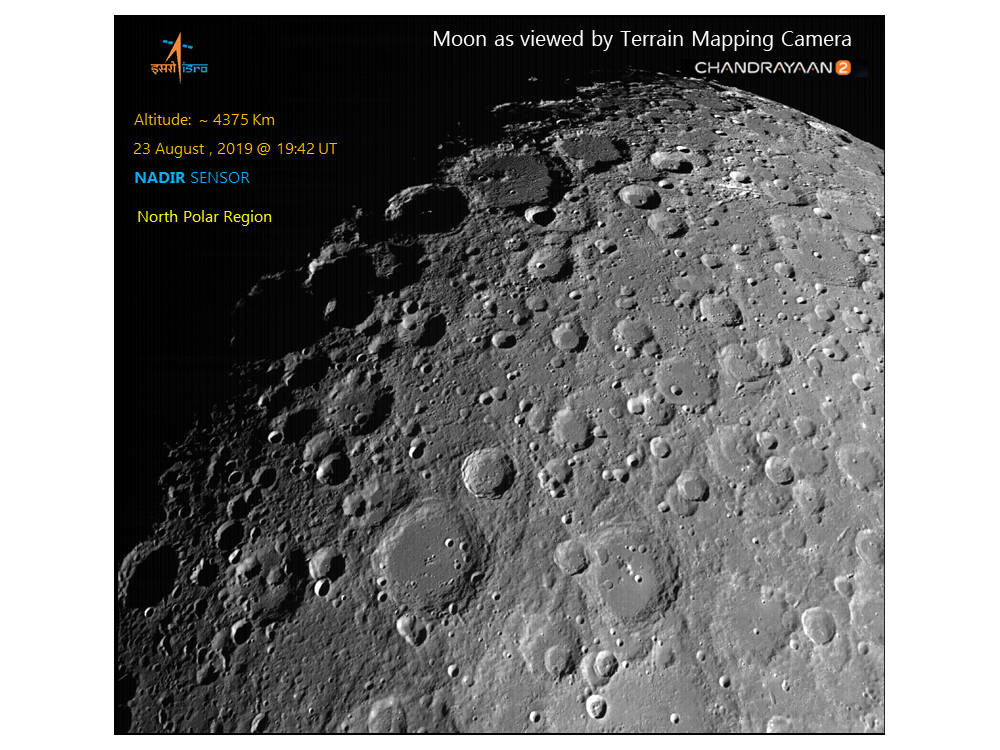

[Images of Lunar Surface captured by Terrain Mapping Camera -2 (TMC-2) of Chandrayaan 2. Photo from ISRO]

Note: This Week in Disruptive Tech brings to you five interesting stories that highlight a new development or offer an interesting perspective on technology and society. Plus, a curated set of links to understand how technology is shaping the future, here in India and across the world. If you want to get it delivered to your inbox every week, subscribe here.

Aiming for a Billion

Here is an ISRO story from Dr APJ Abdul Kalam.

“While I was working at ISRO, I had the best of experience which won't come from any university. I will narrate that incident. I was given a task by Prof Satish Dhawan the then chairman, ISRO and director, Indian Institute of Science, to develop the first satellite launch vehicle SLV-3, to put ROHINI Satellite in orbit. This was one of the largest high technology space programmes undertaken in 1973. The whole space technology community, men and women, were geared up for this task. Thousands of scientists, engineers and technicians worked resulting in the realisation of the first SLV-3 launch on 10th August 1979. SLV-3 took off in the early hours and the first stage worked beautifully.

“But the mission could not achieve its objectives, as the control system in second stage malfunctioned. There was a press conference at Sriharikota, after the event. Prof. Dhawan took me to the press conference. And there he announced that he takes responsibility for not achieving the mission, even though I was the project director and the mission director. When we launched SLV-3 on 18th July 1980, successfully injecting the Rohini Satellite into the orbit, again there was a press conference and Prof. Dhawan put me in the front to share the success story with the press. What we learn from this event is that the leader gives the credit for success to those who worked for it, and leader absorbs and owns the responsibility for the failure. This is the leadership.”

Listening to this story, it’s easy to ignore a more fundamental lesson. Such hiccups are common when you are aiming for something big and bold. It’s not just SLV that started with a failure. Of the four ASLV launches, the first two failed. Of the first seven GSLV launches, three failed. Even PSLV, ISRO’s workhorse, started with a failed launch back in 1993. All complex, tightly coupled systems open themselves to failure. You move on, but keep learning.

ISRO’s Chandrayaan 2 did not complete one of its mission objectives as planned—to softland the Vikram lander on the Moon. It was a sad news to wake up to (and in the case of millions of Indians who were awake to watch it live, a sad news to go to bed with). But, when it comes to science and space, it’s important to remember that it’s a marathon, and it’s not yet over.

Dig Deeper

- Meltdown: Why our systems fail and what we can do about it, by Chris Clearfield and András Tilcsik (extract) | Big Think

- India in Space Science, by AS Kiran Kumar, chairman, ISRO (2016) | Kashmir University, Srinagar

Dept. of Business Ironies

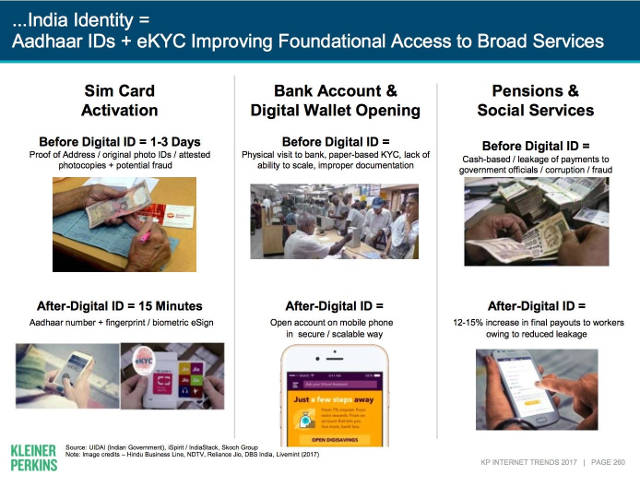

Soon after its commercial launch in September 2016, Reliance Jio scaled up spectacularly fast. Within a month, it had signed up 16 million customers. It reached 50 million in 83 days, 100 million in 170 days, and 200 million in less than two years. It’s often hard to onboard so many customers so fast because dealing with paperwork—collecting KYC documents—can be a big bottleneck. Jio, however, used Aadhaar-based eKYC to do the job not only faster, but at a fraction of the cost. This slide from Mary Meeker’s report captures the benefits companies such as Jio derived from Aadhaar.

By the time the Supreme Court barred the use of the Aadhaar platform by private players, Jio had done its job. Today, we will be hard pressed to think of any other organisation, private or government, that collects as much data as Jio does. And it has plans to collect a lot more. When Mukesh Ambani says data is the new oil, it’s not just an academic observation. He means to mine it. And all these without many questions being asked by the civil society.

The irony is a film from Jio Studios.

AADHAAR - 1.3 Billion unique IDs, one troubled soul!

— Manish Mundra (@ManMundra) September 6, 2019

Experience the journey of life, love and hope as Pharsua scuffles through the system after enrolling for Aadhaar.

Presenting the teaser of #AadhaarTheFilm.

Releasing on 6th December!https://t.co/wiHVdO8UYE pic.twitter.com/6iP6UVBoVu

Dig Deeper

- Free to profits: How Jio, Mukesh Ambani’s $30bn startup, will make returns | Factor Daily

- Reliance strengthens content bid for Jio | Mint

Warren Buffett, Facebook and Deepfakes

Some of the more popular stories about Warren Buffett are about how fast he decides about some acquisitions. “I can smell these things. This one smells good,” he told one founder. But, Buffett also agonises over some of the other businesses he buys. During such times, he hires two investment advisers. He asks one of them to make a case for the acquisition, and the other to argue against it. He listens to both sides. He knows the best arguments for and against it. Then, he decides. The fight between the two ideas happens inside Buffett’s head.

But such duels can take place outside too. Chess players pick strong seconds, and play against them to get stronger. Generative adversarial networks, or GANs, work in the same way.

Suppose you want to create a new work of art in the style of Michaelangelo or Van Ghogh or Picasso that could even fool experts, how would you do it? Do it like Buffett. Get two neural networks, give them both training data, but ask one to generate a fake work, and the other to spot the fake. And create a feedback loop between the two, so the process continues till such time the second one cannot distinguish a fake from the real. You can use the same process to show Elizabeth Warren as saying something that she never said.

Let’s come to Facebook. You might have seen this deepfake of Mark Zuckerberg.

Facebook is worried because its platform could be used to spread such realistic fake videos. It’s already facing heat for violating democractic processes, and as the US presidential elections approaches, there might be a flood of such videos showing people— politicians, judges, journalists, common people—saying things they never said. The heat will turn up. Tighter regulations will loom larger. It won’t be good for the business. Facebook has to figure out a way to spot the fake videos before any of that happens.

And approaches like GANs can make it really difficult. So, Facebook has asked its AI team to develop deepfakes so it also gets the capacity to identify them. It has also set aside $10 million to fund detection technologies through grants and challenges.

Dig Deeper

- How social networks can be used to bias votes | Nature

- Zao’s deepfake face-swapping app shows uploading your photos is riskier than ever | Conversation

AI

Which change would most likely cause a decrease in the number of squirrels living in an area?

- A decrease in the number of predators

- A decrease in competition between the squirrels

- An increase in available food

- An increase in the number of forest fires

Even four or five years ago, it would have been difficult for an AI program to answer such a question that demands slightly more sophisticated language and logic skills. A new AI system called Aristo has shown it can.

In a recent conversation with Alibaba’s Jack Ma, Elon Musk hinted that it’s not the way to think about AI. He said:

“I think generally, people underestimate the capability of AI. They sort of think like, it’s a smart human. But it’s, it’s really much—it’s going to be much more than that. It’ll be much smarter than the smartest human. It’ll be like, can a chimpanzee really understand humans? Not really, you know. We just seem like strange aliens. They mostly just care about other chimpanzees. And this will be how it is more or less in relativity. In fact, if the difference is only that small, that would be amazing. Probably it’s much, much greater. So like, the biggest mistake that I see artificial intelligence researchers making is assuming that they’re intelligent. Yeah they’re not, compared to AI. And so like, a lot of them cannot imagine something smarter than themselves, but AI will be vastly smarter—vastly.

Dig Deeper

Watch the full conversation

The Problem with Big Data

After launching iPod Shuffle, Apple faced an interesting problem. Apple told its customers that the device will randomly pick up songs from their library, and play it for them. Yet, many listeners complained that it was not random, and that it follows a certain pattern. When you are dealing with large numbers—and iPod was a big hit—more people experience extremely unlikely outcomes.

It’s not just Apple, this phenomenon has led even scientific researchers come to interesting, but wrong conclusions. An essay in The New Yorker explores this phenomenon, and underlines how we have become more prone to such errors in the age of Big Data. Hannah Fry writes:

“It’s not that scientific fraud is common; it’s that too many researchers have failed to handle uncertainty with sufficient care. This issue has only been exacerbated in the era of Big Data. The more data that are collected, cross-referenced, and searched for correlations, the easier it becomes to reach false conclusions.”

Dig Deeper

- What Statistics Can and Can’t Tell Us About Ourselves | The New Yorker

- Fooled By Randomness: My Notes | Farnam Street