[Photograph by Florian Pircher under Creative Commons]

Should you buy a 3D printer for your home yet?

Perhaps, no.

It’s a truism that we overestimate the short-term impact of technology, and underestimate its long-term impact. There are many reasons for this. One of them is that many ignore the speed at which technology advances. McKinsey famously underestimated the market potential of mobile phones. But then, in the 80s mobile phones looked like bricks. The early versions of computers occupied entire rooms.

The hard drive of IBM’s 305 RAMAC above had a storage space of around 5 MB.

The other reason is that we pay too much attention to the experiences of early users. They expect too much and end up getting disappointed. “It’s been recycled as a bedside table,” a customer who bought a 3D printer last year told Bloomberg. Sales to hobbyists might drop 18%. Yet, that’s no indicator of things to come. A fantastic slideshow at Engadget that starts with a photosculpture from 1860s gives a fantastic perspective. As Winston Churchill once said, the farther back you can look, the farther forward you are likely to see.

When it comes to exponentially growing technology though, we just have to look around. With a 3D printer, now, or in the not too distant future, you can: make your own Nike shoes at home, construct a house in a day, build a metal bridge, wear a piece of jewellery, get a new bacteria-resistant tooth, and take a selfie—sort of.

AI and the wisdom of the crowd

Big data has its limitations, as Nate Silver pointed out in The Signal and the Noise: Why Most Predictions Fail but Some Don’t, and it often needs human intervention. But that will be less and less so in the future. MIT Researchers have built a Data Science Machine that can do some of what needed a human touch—and well. Competing against human teams to find patterns in huge unfamiliar data sets, it did better than 615 teams of the 906 that participated.

We just have to look around to see that computers are fast covering the ground. A lot of money is being poured into it. Facebook wants its algorithms to do what humans are good at—language and vision. Some of those Buzzfeed headlines—the clickbaits that you fell for—were actually written by computers. Independently, they might look like small steps, but together, it could represent a leap. James Surowiecki’s book, Wisdom of the Crowds: Why the Many are Smarter than the Few was about how aggregated human judgement can often be better than expert judgement. What if that aggregation is done by computers? Welcome to Networked Intelligence. Elon Musk says Tesla’s newly introduced auto pilot feature is all about that.

“The whole Tesla fleet operates as a network. When one car learns something, they all learn it. That is beyond what other car companies are doing,” Fortune quotes Musk as saying. It’s like a positive feedback loop applied to a network—promising to get better and better.

Where will it end? It will plateau out at some point, argues Pedro Domingo, author of a new book on AI, Master Algorithm. “Look at all the exponential curves like Moore's Law. Exponential curves always taper off in the end, so what you have is these S curves that go up slowly at first and then fast and then slowly again until they stabilize. I think we’re going to see exactly the same thing with AI. We're still in the early days of that, so the world after this phase transition has happened will be very different. We were just talking about some of the ways in which it will be different, but there will be many others. It’s not something that’s going to go on without limits.”

Three charts that tell you where self-driving cars are going

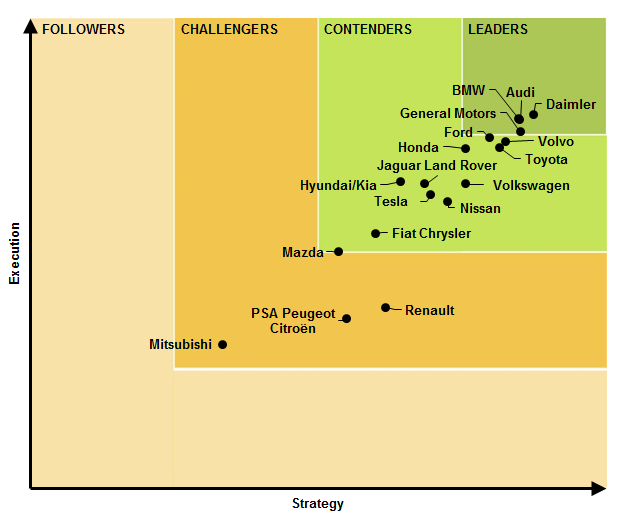

1. Navigant Research Leaderboard Report looked at the strategy and execution of top auto makers, and placed Daimler, Audi and BMW right at the top of the chart. When The Washington Post asked Navigant where it would put tech players Google and Uber, it said, near Mitsubishi.

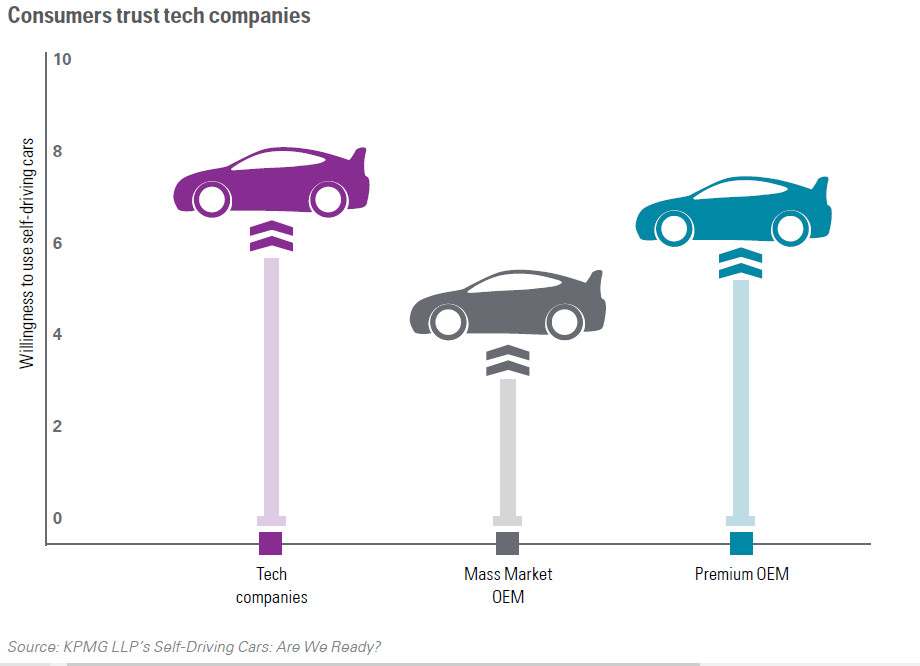

2. Customers trust tech companies more than OEMs, says KPMG .

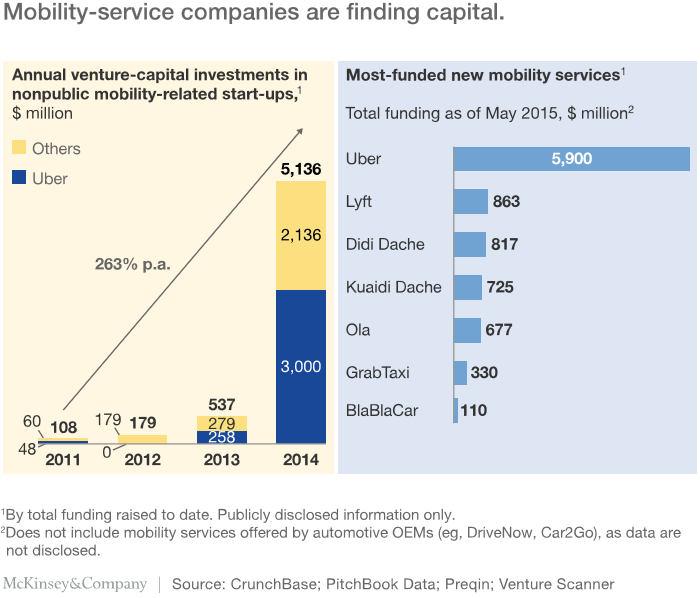

3. Mobility-related start-ups might not be visible at the forefront of technology, but they will be driving the demand, a chart from McKinsey suggests.

The sharing economy and jobs

There is yet another book on how technology is stealing good jobs. Written by Steven Hill, Raw Deal: How the Uber Economy and the Runaway Capitalism are Screwing American Workers argues that the sharing economy replaces full time jobs and accompanying benefits, with freelancing jobs which often pay less, and have no benefits. Hill is not against technology, or capitalism, he said in an interview to Bloomberg, he just wants a better deal for workers.

That seems to be top-of-the-mind for governments too. Singapore is studying the ride-sharing market, and wants to create a level playing field for the companies. In UK, politicians are still arguing on what it is, and how services such as Uber and Airbnb will impact people. In Australia, the opposition party seems to be optimistic over all. In the US, a survey revealed job seekers are more open than ever—more than 50% of job seekers have considered working in the sharing economy according to a study—thanks to flexibility, earning potential, and freedom from office environment, even though lack of full-time benefits is a discouraging factor.

How to save rhinos, fix roads, and prevent disasters

Using drones, of course.

Conservationists in the wild use camera-enabled drones, backed by some sophisticated software to identify the likely targets—from a specific herd of elephants, or a crash of rhinoceros—for poachers, and try to stop it. It seems to have worked.

In the US, a company is working with a university to make drones that would inspect bridges—which was traditionally done by workers using scaffolding or extension ladders. Drones inspecting bridges will just be one part of a jigsaw with many pieces. Researchers at Leeds are working on building robots that would fix urban infrastructure—repair street lights, fix potholes, and spot cracks in pipelines. The smart cities of the future will correct themselves. A quality some human beings might be lacking.

A couple in the US recently found outside their second floor window a peeping tom staring at them, a drone with a camera. It flew away soon after it—rather, the person operating it—realised it had been spotted.