[From Unpslash]

When we started to brainstorm some time ago on how do we celebrate the idea of India at 75, one idea resonated with everyone. What will it take to identify the stories of lesser known places across the country that contributed to the India we live in now? Who were the people that made it happen? The only caveat was that well-documented places be left out.

While the idea was appealing, it appeared daunting as well. Just how could we possibly pull this off? India is a large country, the stories are dispersed, and this is what professional historian’s do.

The only way out was to reach out to people in the Founding Fuel network with deep expertise in their domains and an understanding of its history. We did just that with a request: What place do you think we must visit? What happened (or happens) there? Who were the main people in that story? What is the untold story of your recommendation?

We told them, these need not be limited to a political event or movement. It could include landmark science and technology institutions; modern India’s evolving culture (art, theatre, music); or new sensibilities and awareness. In fact, anything in their field of expertise that they believe has had a significant impact on contemporary India or holds the potential to be transformative.

The response was immediate and overwhelming. While there were places we had no clue about, there were others that were always in sight, but the backstories to which we had no idea about. We spent hours listening to compelling stories and were hard-pressed to choose. But we had to stop someplace. That is why this list is limited to 21.

We hope you enjoy reading about this as much as we enjoyed putting it together. And we certainly hope these places weave their ways into your hearts and heads as places that must be visited.

Happy Independence Day!

Team Founding Fuel

1. Akashvani Bhavan, Kolkata

Ruling the airwaves over generations

[By John Meckley, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

This iconic building was built in 1958, when All India Radio Kolkata, the second oldest radio station in India established in 1927, moved its (arguably haunted) headquarters from 1 Garstin Place to this prime location next to the Eden Gardens.

Accorded a Grade-I heritage status by Kolkata Municipal Corporation, the structure has a unique architectural style, representing the amalgamation of Hindu and Buddhist forms of art.

Akashvani Kolkata is considered to be the birthplace of modern music and cultural renaissance of Bengal. Some of the famous personalities once associated with this station were: Birendra Krishna Bhadra, Pankaj Mallick, Bani Kumar, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Sombhu Mitra, Suchitra Mitra, Ajitesh Bandopadhyay, Soumitra Chatterjee, Kanika Banerjee, Uttam Kumar and many others.

All India Radio is the largest radio network in the world, and one of the largest broadcasting organisations in the world in terms of the number of languages broadcast and the spectrum of socio-economic and cultural diversity it serves. Today four Medium Wave and three FM channels are run from this Bhawan, a hub of Prasar Bharti.

Its record archives comprise a collection of rare voice documents including those of Rabindranath Tagore and Subhas Chandra Bose. One of the most longstanding popular radio programs, Mahishasurmardini, earlier performed from this location as a live program by famous artistes, continues to be the harbinger of the Durga Puja season; listening to the sonorous chants of Birendra Krishna Bhadra is a ritual for several generations of Bengalis around the world. A Bengali film titled Mahalaya, based on this radio station, was released in 2019. A series of three books named Kolkata Radio was released in 2016 to commemorate its cultural legacy.

(I was fortunate to have been associated with a well-known children’s programme “Calling All Children” between 1966-71 in performing plays, poetry-reading and debates alongside contemporaries like Shashi Tharoor and under the mentorship of stalwarts like Adity Syam, Barun Haldar and Sadhana Dutt in these hallowed precincts. We were paid the princely sum of Rs 5 per participation – my first ‘income’ from the age of 10!!)

Go down memory lane with the AIR Signature Tune.

2. Bahadurshah Zafar Marg, ITO, New Delhi

Informing India’s journey

Bahadur Shah Zafar (BSZ) Marg was once an arterial road that linked old and new Delhi, till it was developed as one of the institutional areas of Delhi through the fifties.

In 1957, Ramnath Goenka constructed the Express Building, next to the Shaheed Bhagat Singh Park on BSZ. Around the same time, The Patriot, National Herald, The Times of India group, Urdu Milap, and much later, Businessworld and Business Standard also moved in. Since then, India’s Fleet Street has been an active participant in almost every twist and turn in a chaotic, noisy democracy.

Through the sixties to the nineties, at least four generations of journalists worked in offices along this narrow one km stretch. And built their reputations, documenting the rise and fall of governments, scandals, natural disasters, covering the turning points in sports, business, and even entertainment.

When the internal emergency was declared in 1975 and civil liberties were suspended, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had Srikrishna Mulgaokar, the then editor-in-chief of The Indian Express, removed and senior editor Kuldip Nayar arrested. Soon after the emergency, Mulgaokar returned to his editorship and almost single handedly exposed Indira Gandhi and her son Sanjay Gandhi for their transgressions during the emergency. It resulted in an embarrassing rout for Mrs Gandhi in the 1977 general elections.

During its heydays, the street would be abuzz with chatter around the latest scoops and gossip, over copious cups of tea and cigarettes. This din would die down for a few hours after sunrise. Through the night, the printing presses in the basement of the buildings would crank out the early city editions, which would then be dispatched through hired cabs to towns across north India. The smell of printing ink was all pervasive.

Then, in the early nineties, Times TV began to produce its current affairs programmes like Turning Point for Doordarshan. Times FM launched the first private FM radio programme for All India Radio.

Around the turn of the century, as printing gradually shifted to other parts of Delhi NCR, publications too started shifting some of their operations to bigger, modern facilities in Noida and Gurgaon. Some new digital media firms have since filled the void.

Even today, the Udipi Cafe, the popular restaurant on the ground floor of Pratap Bhawan, which also houses Business Standard, still does brisk business. The roadside food stalls on the entire stretch are as busy, but not as much at night. The Metro has helped reduce the traffic chaos.

Clearly, BSZ Marg has seen better days. Yet, for journalists who cut their teeth in the profession for more than six decades after Independence, BSZ still evokes memories of an old world charm that’s somehow gone missing in the digital age.

3. Bihar Museum, Patna

Celebrating heritage in modern times

The new Bihar Museum, inaugurated in August 2015, is as much a paean to modern design and international collaboration, as it is to Bihar’s history. It reflects both the past and the future.

One gets a sense of that heritage even before one steps in. For example, the building, designed by Japanese firm Maki and Associates, uses weathering steel (cor-ten steel) as cladding material—a symbolic connection to the use of iron, metallurgy, and industry since ancient times.

Inside too, everything is specially designed, from stonework, to displays and even furniture. The emphasis is on creating a memorable, sensory experience for visitors as they view the priceless artefacts. By telling stories through the displays rather than just artefacts on pedestals; by letting children touch and feel the displays in the children’s gallery; and by letting visitors enter a different, quieter world. (The architect created seven courtyards, to reduce the sounds of the city.)

All of this is rooted in a sensibility that the museum has to play a role in society by bringing in new ideas, technology, and design.

Though just seven years old, the museum follows international best practices, collaborates with international museums, and is one of the few artefact museums in India which has already broken even on its operational costs.

And it’s not ready to rest on its laurels just yet. Post-pandemic, when footfalls stopped, it went digital, so people can also visit virtually. It is now building an art tunnel to connect to the old Patna museum. The Bihar Museum will house pre-1800 archaeological finds, while the Patna Museum will be modern and contemporary. The idea is that if you want to see the history of Bihar, you have to see both museums—and will be possible with one entry ticket.

4. Brabourne Stadium, Mumbai

A Lord’s in Mumbai

[By Ajay Goyal, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons]

The story of Brabourne Stadium starts with Lord Brabourne, who allotted 90,000 square yards to the Cricket Club of India (CCI), for the construction of India’s first permanent sporting venue. The intention was to build a stadium that could match the prestigious Lord’s in London. The stadium, named after the lord who built it, has etched itself into the history of cricket, through the matches it has hosted and the sportsmen who lavish it with praise. Keith Miller, the Australian all-rounder, once referred to it as the “most complete stadium”.

Brabourne became the home of the Mumbai Cricket Team, and hosted 16 Ranji Trophy finals, 14 of which Mumbai won, and was the site of India’s first test series victory, winning 2-1 against Pakistan. The match was also the first test result produced at Brabourne. Famous matches against Australia in the 60s followed, with one herculean draw in 1960 and one close victory in ‘64. The last quarter of the 20th Century proved to be lacklustre for the stadium. Following the construction of the Wankhede Stadium just half a kilometre away, test cricket disappeared from Brabourne.

A return of test cricket in 2009 brought with it a spectacular Indian victory. The opening pair of Sehwag and Murali Vijay put together a double hundred partnership, followed by a Rahul Dravid masterclass. Today the CCI houses athletes from the sports of tennis, squash and badminton in addition to its continued support for young cricketers.

But Brabourne is not a must-visit just for its cricketing history. Instead it’s about what Brabourne meant to a young nation. A symbol of an imperial past which offered an opportunity for excellence on an international stage for a young India. Brabourne served as the stage from where Nani Palkhivala once broke down the essence of the government’s budget, with the entire nation as his audience. The CCI’s lawns became more than just a cricket pitch. On those days, Brabourne became a courtroom, the Indian taxpayers the jury, and Nani Palkhivala, the examining attorney.

India is no longer young, and the hallways of Brabourne are no longer the pristine white they once were. Instead, murals of the famous Indian cricketers who have shook the stadium across the decades adorn the walls. These stars form an integral part of modern Indian history, and the sport they played still helps define what it means to be Indian, 75 years on from 1947. The spirit of the stadium can be best captured in the words of the Maharaja of Patiala: “We will build a monument in this jungle, and even Lord’s will look mediocre.”

5. Corbett Museum, Kaladhungi, near Nainital

Tiger Jim

Just 30-odd minutes from the Jim Corbett National Park sits a heritage bungalow—the hunter-turned-naturalist and conservationist’s winter home that he built in 1922. A childhood and youth spent rambling in the forests behind this and the family’s earlier winter home Arundale—now in ruins—groomed Jim Corbett (Carpet Saheb and Gora Sadhu to the locals) to be a good tracker and hunter of man-eaters. Many of his books on hunting man-eaters were written here.

Corbett sold the house when he left for Kenya in 1947. In 1965 then forest minister Charan Singh requested the new owner to sell it to the government for a museum dedicated to Corbett.

The museum displays his belongings, maps marking the spots of his kills, pictures, letters and paintings—like the one of him with the ‘Bachelor of Powalgarh’ that he killed in 1930. Book readings and plays on Corbett are also staged here on occasion.

But Corbett’s enduring legacy is captured in these lines from his book Man-Eaters of Kumaon: “The tiger is a largehearted gentleman with boundless courage, if it is exterminated India will be the poorer by having lost the finest of her fauna.”

Though a hunter, Corbett was sensitive to human-wildlife conflict and habitat destruction. He established the national park in 1936 mainly for the protection of the Bengal tiger. The Indian government named it after him in 1957—two years after his death. This is India’s first national park and the one best identified with tiger conservation in people’s minds. It was here that India’s Project Tiger was established in 1973. The park is part of the larger Corbett Tiger Reserve—which has one of the highest tiger densities in India.

6. Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary

A refugee camp

By M Rajshekhar

When it comes to conservation, there is scientific research, advocacy that seeks to merge science and local concerns, policy-making. And then, there is conservation itself, that needs both state and non-state actors.

In this spectrum of actors, Gurukula Botanical Sanctuary occupies a unique position. Much like Norway's Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which stores seeds of 1.1 million crop varieties—to ensure unique crop genetic material from across the world does not get lost to threats such as natural disasters and monoculture among others—Gurukula is a fire-fighting response to the global biodiversity crisis. Set up 50 years ago by German conservationist Wolfgang Theuerkauf, it is now run by settler-farmers, tribal and regional. What they do is extraordinary. Whenever the team hears of an endangered forest fragment in the hugely biodiverse Western Ghats, they visit the place to rescue the endangered species. This is then brought back to Gurukula where the team rears the species, in the hope of reintroducing it back to its habitat someday. As the team told Al Jazeera: Gurukula is like a “refugee camp”.

This is intensely important work because ecosystems that are in peril can be revived; extinction is permanent. The history of life on Earth might be one of resilience. But a species that takes millions of years to evolve, once lost, will not emerge again. Ours is a time when fire-fighting is needed. To know more about Gurukula, do read this and this.

7. Himalayan Mountaineering Institute (HMI), Darjeeling

Tenzing Norgay’s stomping ground

[Courtesy HMI]

The HMI was set up in 1954 to capitalise on the huge groundswell of popular interest generated by Edmund Hilary and Tenzing Norgay’s Everest ascent the previous year. The idea was spurred on by Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, who realised it was a great opportunity to channel energies of the youth towards mountaineering, and had the backing of the then West Bengal chief minister BC Roy.

As the first Sherpa mountaineer to scale Everest, the local people saw Tenzing Norgay as a living legend. He took on the role of HMI’s Director of Field Training and remained the heart and soul of the institute till his death in 1986. According to a New Yorker profile on Norgay published in 1954, there was a huge demand to rename Mount Everest after Tenzing, but that didn’t eventually see the light of day. In fact, shortly after the Hilary-Norgay duo began heading back to Kathmandu after their conquest,, there was an uproar among Nepalese and Indian media that it was Norgay who was the first to reach the summit. They wanted to prove that Indian and Nepalese climbers were on par with the foreigners. “We felt quite uncomfortable with this at the time, John Hunt (leader of the expedition), Tenzing and I had a little meeting. We agreed not to tell who stepped on the summit first,“ recalled Sir Edmund in 50 years of Everest, a multimedia project led by National Contributing Editor David Roberts. “To a mountaineer, it’s of no great consequence who actually sets foot first. Often the one who puts more into the climb steps back and lets his partner stand on top first.” The pair’s pact stood until years later, when Tenzing revealed in his autobiography, Tiger of the Snows, that Hilary had in fact preceded him.

8. The Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata

Counting on excellence

By Abhik Ray and Sanjoy Bhattacharyya

Before anyone in the country knew of statistics as a formal subject, or thought of learning and teaching it, Prashanta Mahalanobis, a professor of Physics at Presidency College, started a Statistical Laboratory from his own room in the department. In December 1931, this modest laboratory grew into the Indian Statistical Institute, one of the earliest places of research and learning in statistics in the world.

And since then, ISI has remained at the forefront of academic research globally. If statisticians from India are considered the best in the world, on par with those from Russia and Hungary, a lot of that credit goes to ISI’s pioneering work. Nobel prize-winning economist Angus Deaton wrote “Where Mahalanobis and India led, the rest of the world has followed … Most countries can only envy India in its statistical capacity.”

Sankhya, the academic research journal that Mahanalobis started in 1933, remains the most prestigious journal in theoretical statistics in the world. Leading academicians in MIT and Stanford jostle to publish their work to earn tenure. Admission into its flagship three year Bachelor of Statistics (Hons) programme is even more stringent than IIT-JEE. Only 25-odd students get in through the general quota every year. Except for a small hostel fee, the entire tuition and board is funded by the institute, without having to sign any bonds. Upon graduation, students get lapped up by leading global tech firms, often at salaries higher than the IITs.

The academic experience has been shaped, thanks to some of the biggest names in economics and statistics who have either taught or studied there. CR Rao, considered to be one of the top ten Indian scientists of all time, taught at the ISI. The Cramer-Rao bound theorem is one of the most fundamental bodies of work in mathematical statistics.

Yet, despite its global impact, and unlike many of the leading IITs, ISI continues to face an enormous funds crunch.

9. INS Khukri Memorial, Diu

The untold battle of Khukri

On December 9 1971, in the icy waters of the north Arabian sea, off the coast of Diu, an anti-submarine frigate of the Indian Navy, hunting for a Pakistani Daphne class submarine, deployed silence and stealth as weapons. It was hunting for a Pakistani submarine, the PNS Hangor. A gripping battle followed and most narratives have it that the Type 14 (Blackwood class) Indian frigate was hit by torpedoes from the Pakistani submarine. And INS Khukri was sunk 40 miles off the Diu coast and took down 18 Officers and 176 crewmen on board. This battle is solemnly remembered as the Indian Navy’s greatest wartime tragedy.

But the 67 who survived have another tale to tell. That of Captain Mahendra Nath Mulla, Commanding Officer of Khukri, a warrior who led from the front. A man who is now revered as a hero whose courage generations of naval officers hope to emulate.

Even as Capt. Mulla ordered his people to abandon ship to save their lives, he battled injury and bleeding from the head. The incredible leader gave away his gear to another sailor. And in exemplary conduct, the 45-year-old skipper chose to go down with his ship, standing on the bridge.

The Khukri crew and Capt. Mahendra Nath Mulla, Mahavir Chakra, have been immortalised at the Khukri memorial in Diu. A scaled-down model of the ship is on display. And recently, the decommissioned INS Khukri was handed over to the Diu administration so a full fledged museum be set up, lest we forget the war of 1971.

10. KEM Hospital (King Edward Memorial Hospital), Mumbai

Many firsts in India’s medical annals

By Deepa Soman and Monodip Chaudhuri

[Seth GS Medical College. By Gsmc_gymkhana - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0]

Few people outside the medical fraternity know that this hospital and the medical college attached to it were built as an act of defiance. It had to do with that when the British ruled over India, only the Sir JJ Hospital and the attached medical college were the premier medical institutions in Western India. But treatment and entry to these places was restricted to Europeans.

And so, beginning in 1915, a group of people, fired by nationalistic fervour, and armed with a phenomenal grant of Rs 2.5 lakh by Seth Gordhandas Sunderdas, a philanthropist with nationalistic leanings, started work to build something that would rival JJ Hospital. When it was ready to be inaugurated in 1926, King Edward VI was visiting India. As ruler of the sub-continent, he did the honours. That is why the hospital is named after him (KEM). But the college attached to the hospital was called Seth GS Medical College to honour the man who made it possible.

Once it opened, many Indians who were practising in England gave up their careers there and came back to set up practice here and India got its first hospital with all Indian doctors. Dr Purushottam Vishwanath Gharpure served as the first dean of the medical college and is credited with creating the oral polio vaccine.

The place has a track record of having created some of the finest teachers in the world who went on to write textbooks on medicine that at least two generations of Indian medical students used. These include Golwalla’s Medicine for Students and Practical Medicine by PJ Mehta. This also explains why the place has earned its place in the books as one of the finest institutions in the world for medical students and continues to attract people from across the world, including the West.

It isn’t without reason that the graduates are sought after. KEM has many firsts to its credit. It was first to have all-Indian doctors from Day One, building the first ICCU in India. The place is full of stories of legends such as the surgeon Dr PK Sen. He performed the first human heart transplant in India in 1968. Dr Sen was among the pioneers in the world around the time geniuses such as Dr Christiaan Barnard of South Africa were at work to perfect the technique. Dr Sen was the sixth surgeon to attempt the procedure anywhere in the world. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan for his contribution to medicine in India.

11. Kalakshetra, Chennai

A temple to Bharatnatyam

By Founding Fuel

Today Bharatanatyam is revered as a reflection of the best of Indian art and culture. It’s performed in some of the most hallowed venues. Students from across the world seek to learn with reverence, feeling they are a part of an unbroken tradition stretching back to Natya Shastra composed by Bharata Muni sometime between 200 BC to 200 AD.

Yet, in the 1900s, the dance was looked down upon by most members of society. It was solely practised by the Devadasi community. The British administration in Madras had banned it as a part of ‘social reform’. The art form itself seemed to be on the verge of extinction.

What changed? The answer, for most part, is Rukmini Devi Arundale and Kalakshetra, a dance school she founded in 1936. She revived the art form, removed the stigma around it (by rechristening Sadir as Bharatanatyam, among other things), collaborated with scholars, choreographed dance dramas, and made it popular among art lovers.

In a lush green campus, a veritable oasis amidst the rush and bustle of the city, she nurtured the institution based on the gurukul model. The morning prayer session is held under a huge banyan tree.

The learning takes place in breezy classrooms, sometimes in open air. The auditoriums are beautifully designed. Its alumni list includes several recipients of Padma and Sangeet Natak Akademi awards.

The institution has also long been a reflection of her strong personality, says V Sriram, author of Chennai, A Biography. Its visual arts department, for example, reflects her interest in handloom and textile printing.

A few years after Rukmini Devi's death, the institution was taken over by the government, and is now an autonomous body under the ministry of culture.

12. KISS-DU, Bhubaneswar

An oasis for diversity and inclusion

The Kalinga Institute of Social Sciences Deemed to be University (KISS-DU) is tucked away in a massive campus on the outskirts of Bhubaneswar.

Down a dusty road, as you turn a corner, it’s like driving into a fresh green oasis. Clean and orderly, where even the walls and tree trunks are decked out with tribal art. This is one of the buildings of the sprawling 100-acre KISS-DU campus where 30,000 indigenous children live, learn and laugh together. The campus houses preschoolers, post graduates and doctoral students, with access to world-class facilities.

The founder, Dr Achyuta Samanta, experienced hunger and deprivation as a child, and he uses those life lessons to ensure that others don’t suffer like he did. His simple objective is to ensure that every tribal child gets an education in a safe environment with all their physical, intellectual and emotional needs taken care of.

Parents are encouraged to send in their children at age five. The curriculum is designed to encourage assimilation without indoctrination and maintain their cultural ethos. They come in speaking their local dialects—most don’t speak Oriya, leave alone Hindi. Each dialect has a language lab where the young children are taught Oriya by teachers who speak their own dialects.

The way the institution embraces diversity and builds unity is a strong lesson for all of us in this 75th year of Independence.

Sport is one of the greatest unifiers and the outstanding performance of the boys and girls in the global Rugby league is proof that given the right training and nutrition even the most economically backward can lead the world.

Pride and respect for traditions is another strong unifier. The children are helped to preserve and understand their cultures and practices by a team of professors of practice. Tribal leaders ensure that the children get access to their dialects, instruments, art, culture and ethnographic traditions.

Doctorate students are encouraged to study everything from rites and rituals to traditional medicines. The amazing diversity of subjects is an eye opener for all of us who have been weaned on a diet of Arts, Science and Commerce.

None of the IITs or IIMs come anywhere close to KISS-DU. Because this institution is truly a safety net for those India has forgotten.

13. Mehboob Studio, Mumbai

A history of drama

By Abhik Ray & Arjun Chaudhuri

Mother India remains etched in the minds of Bollywood enthusiasts as one of the pre-eminent movies of Indian cinema. Similarly canonised is the studio where the movie was produced: Mehboob Studios. Producer-director Mehboob Khan built the studio in order to have a filming location in Central Mumbai, finally settling in Bandra, close to the homes of the industry’s biggest talents.

The studio earns its place on this list as a result of its services to Indian cinema. It may not be the most prolific of studios, the richest or even the largest. But it’s roster of films is studded with some of Hindi cinemas most iconic films, and its location made it a hub of scandal and creativity. Apart from Mother India, the studio filmed Guide, Kaagaz ke Phool, and more recently, Chennai Express. Mehboob’s greatest impact, however, extends beyond the movies filmed there, or the stars who set up offices in the complex. Instead, the studios’ adaptability and longevity in the face of threats to its very survival, make the studio a historic landmark in Mumbai.

The 1960s were particularly harsh for the studio. Khan’s passing, and the substantial debts he left behind prevented the studio from upgrading its facilities, and the sets fell out of favour. However, with the rights to Mother India returning to Khan’s family in the 70s, the studio once again became a hub of activity. Then came the fire in 2000, which destroyed two stages. The studio once again recovered and became the spot from which many commercial blockbusters were filmed.

In more recent times, the studio has become a centre for culture in Mumbai. Built in the leafy lanes of Bandra, in between cafes, colleges and bookstores, the studio now hosts public events, exhibitions and even literary discussions. Today, Mehboob Studio stands as a reminder of the influence that Bollywood had in building a sense of Indian identity in a post-Independence period that was highly charged with regional and religious divides. Bollywood served as the first highly visible, truly pan-Indian industry. The movies, filmed and produced in studios like Mehboob, shaped the popular thinking and values of early independent India. The studio stands as a monument for a movement which helped unify India, through Mother India.

14. Mulkanoor Cooperative Rural Credit & Marketing Society

A cooperative with pragmatic rules

By Founding Fuel

[Paddy processing unit at Mulkanoor. By Mulkanoor Cooperative]

Mulkanoor Cooperative is one of the few examples of well-run cooperatives in the country. Its success is based on a number of decisions it took early on in the fifties under the leadership of its first and long-time president A.K. Vishwanatha Reddy and the way it has been responding to the changes in the market.

Primary cooperatives—such as Mulkanoor—typically leverage 10 times their share capital, and as do their members. In the case of Mulkanoor, while it went for 10X leverage, its members’ leverage was restricted to 5X. The cooperative used the headroom to get into related businesses, such as selling seeds, fertilizers, farm equipment and so on. As it accumulated capital, it could invest in larger projects such as paddy processing units.

This essentially meant it could provide its members—all of them farmers from 14 villages in the Warangal district, bordering Karim Nagar district—services across the value chain. Provide them loans, offer allied services, and buy the products at higher than market rates.

Geographic concentration also meant it developed a deep understanding of its members—always a plus in credit businesses—and the members felt a strong sense of ownership. This reflected in Mulkanoor's other businesses too. When its members moved from maize to paddy, it set up processing centres for paddy. When the interest in cotton went up, it set up ginning facilities. When the members set up poultry farms, it pivoted to poultry. Part of the reason is its growing capital base.

With clear boundaries in terms of geography (the 14 villages cover about 18,000 hectares) and membership (open to those who own farm land), Mulkanoor showed what a cooperative with pragmatic rules and quick response times can achieve. While its model cannot be transplanted to other sectors or even geographies, there's much to learn from the principles it operated on.

15. Potti Sreeramulu Memorial, Mylapore, Chennai

The genesis of linguistic division of states

By TN Hari

[By Badri Seshadri]

If you are in the vicinity of Potti Sreeramulu Memorial House in Mylapore, Chennai, there is a good chance that you will miss it. It looks inconsequential—like hundred other buildings in any middle class neighbourhood in the city. In 1952, a leader widely acknowledged to be one of the sharpest minds in Indian politics, believed that an event that took place in the very same place was inconsequential. He turned out to be so wrong.

That year, in this very same location, Potti Sreeramulu went on a hunger strike demanding a separate state for Telugus. C Rajagopalachari, chief minister of the undivided Madras state, didn't pay much attention to it, partly because he didn't believe that states should be formed based on language. On the 56th day, Sreeramulu passed away. It led to riots. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who held similar views as Rajaji, was forced to change his mind. His death led to the formation of Andhra Pradesh, and The States Reorganisation Act, 1956.

The immediate consequence of his death is well recognised. He is a revered figure in Andhra Pradesh. Nellore District, where he hails from, is officially called Sri Potti Sriramulu Nellore district. The memorial itself is maintained by the Andhra government. His role in the linguistic division of states is less acknowledged, but as important.

16. Reliance Jamnagar

Animal spirits

By Rajesh Srivastava, Debasis Ray & Srinivas Eranki

It was an audacious bet, quite simply the largest industrial project ever implemented by the Indian corporate sector. At another level, it also symbolised the animal spirits of one of India’s greatest post Independence entrepreneurs. Dhirubhai Ambani, who started off with modest beginnings, was unwilling to accept the shackles imposed by the licensing raj. He dreamt global scale—and Jamnagar was his final hurrah, two years before his death in 2002.

After he was left paralysed by a stroke, the hugely complex project was helmed primarily by his son, Mukesh. In December 1999, when the world’s biggest greenfield refinery complex—and entire township with it—was commissioned in less than 36 months, it left everyone in awe. On June 8, 1998, a super cyclone wreaked havoc on the Gujarat coast, killed thousands and flattened incomplete structures on site. The Reliance team staged a remarkable comeback by resuming work in 12 days. That wasn’t all. By 2008, Reliance pulled off another huge expansion at the same site, doubling capacity at one go. No wonder the story of the Jamnagar refinery project remains a case study in execution. And decisively helped place Indian business on the world map.

17. Society for Education, Action and Research in Community Health (SEARCH), Gadchiroli, Maharashtra

What they don’t teach you at Johns Hopkins

By Founding Fuel

When Dr Abhay and Rani Bang returned to their home town in Gadchiroli in 1986, after completing the Masters programme in public health at Johns Hopkins University, they realised they would have to first unlearn—and then relearn how to practise medicine. Today, 37 years later, their community health model is seen as a role model to deliver healthcare to not just the remotest parts of the country, but has been adopted in many other parts of the world as well.

Yet it wasn’t easy in the early years. Gadchiroli district was among the poorest in the state. The large tribal population were wary of modern medicine, preferred traditional cures—and lived far away from the big cities where better healthcare facilities were available. It was a deadly cocktail. Many pregnant women died giving birth. Infant mortality was among the highest in the country and intoxication claimed the lives of many men and ruined families. The initial efforts to serve the tribal community were rebuffed. In fact, the Bang couple and their teams were even stoned by the villagers when they tried to help them.

Along the way, the Bangs learnt a few precepts of their own. One was to first listen to the people, understand their problems. And resist the temptation to jump in with their own preconceived notions of the problems to solve. Two, the solutions to rural health were unlikely to be found in expensive facilities, which were a preserve of the big cities. You had to live and work among the people–something that Abhay learnt during his stay at Sevagram in Wardha, where Gandhian principles of frugality and service were held dear. And research wasn’t meant to be just an intellectual pursuit, it needed to solve the needs of the community. The beauty of their model is that it does not depend upon doctors, nurses, hospitals or costly equipment. For instance, it trained a village health worker to provide home-based newborn and child care, thereby reducing the infant mortality rate—the number of infant deaths for every 1,000 live births—from a baseline of 121 to 22 currently.

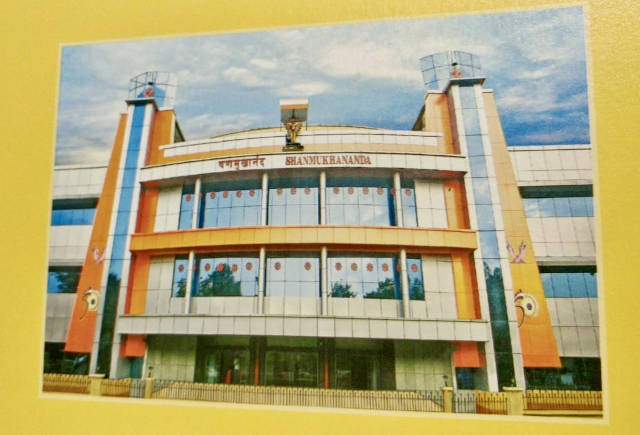

18. Shanmukhananda Auditorium, Mumbai

Rising from the ashes

By Founding Fuel

[Courtesy the Sri Shanmukhananda Fine Arts and Sangeetha Sabha]

Built in 1963, the grand Shanmukhananda auditorium in Sion is considered a shining example of Mumbai’s syncretic and cosmopolitan culture.

Every major Indian artiste has performed there. Be it the dulcet strains of Pandit Ravi Shankar’s sitar, MS Subbulakshmi’s soulful Carnatic singing or the stirring performance of the New York Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Zubin Mehta. Discerning audiences have enjoyed it all.

Before the hall was constructed, there were many Carnatic music groups in the city. In April 1944, they eventually joined hands to create the Shanmukhananda Sabha. However, there was no auditorium that could accommodate so many people at one go. Backed by the combined power of its members, the largest such auditorium in Asia, with the best acoustics, was finally inaugurated by the then state Governor Vijaylakhsmi Pandit.

Built at a cost of Rs 27 lakh, the auditorium played a pivotal role in Mumbai’s cultural landscape for nearly three decades. Till a devastating fire destroyed the stage and parts of the auditorium in 1990. During a school performance, a child on stage inadvertently dropped a lit candle on the curtains—and within minutes, the fire spread across the stage and the roof of the auditorium.

The cost of repairs was formidable. And the insurance claim was meagre. The Sabha did not have the funds to go ahead with the reconstruction and repairs. A huge drive to mobilise funds was undertaken. The Central government and the state governments of Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, among others, and a clutch of business organisations, from BPCL, SBI, ICICI, BoB, and Jasubhai Foundation raised a corpus of around Rs 13 crore. And in 1998, the auditorium was reopened.

Eventually, the new structure turned out to be even better than the original, with the capacity to hold different cultural activities, the facade of a traditional South Indian temple, yet with a modern sophisticated state-of-the-art equipment and a well-planned infrastructure.

19. Sourashtra Boys Higher Secondary School

A catalyst for universal education

Education is the passport to a better life. But, primary education in India was plagued with lack of enrollment and dropouts.

The mid day meal scheme changed all that. It upturned the equation in the minds of parents across the country. It has been the single most significant catalyst in the growth of primary education in the underbelly of India.

It all began in Tamil Nadu.

It was during a visit to Madurai, Tamil Nadu, in 1921 that Mahatma Gandhi gave up his traditional Gujarati attire for the iconic loincloth and shawl. A high school in the temple town, which also has Gujarati connections, has inspired something even more substantial.

Sourashtra Boys Higher Secondary School, a 130-year-old institution, initially founded for a community that migrated from Gujarat, was among the first to offer midday meals to the students to incentivize school attendance. In the mid fifties, K Kamaraj, a pragmatic chief minister of Tamil Nadu, visited the school, and was impressed by the programme, and implemented it in some of the state-run schools.

In the mid eighties, another chief minister, MG Ramachandran, who had experienced poverty as a young boy, implemented it across all state-run schools. Other states followed. In the 2000s, following a Supreme Court order, it was made compulsory across the country. Several studies have since shown that the midday meal programme has led to better health and educational outcomes—higher attendance, better learning—among children.

Sometimes, the places where great movements start fall into disarray, and are preserved only for their historical value. Sourashtra School, however, has continued the tradition without a break, and has expanded to serve breakfast as well.

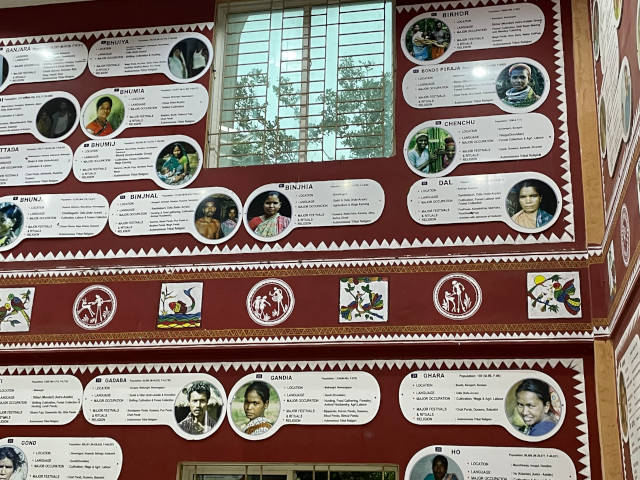

20. Tribal Culture Museum, Pune

A peek into tribal culture

By Sanghamitra Shastri and Satish Pradhan

If you’re driving in a rush to get to some place in Koregaon Park in upmarket Pune, you might just miss the Tribal Cultural Museum.

The beauty behind the museum isn’t just the history it boasts of, but it is the way in which it just exists on one of the busiest roads of the city, modestly. It’s a testament to how we also look at tribes today as youngsters and the richness they bring to our collective culture as a nation.

Established at the campus of the Tribal Research & Training Institute in 1965, the Tribal Culture Museum safeguards the stories that shape the contribution of over 45 tribes to the culture of Maharashtra with a library equipped with books that explain the tribal culture in detail.

Among the 1,300-odd exhibits on display are musical instruments, jewellery and tools, among other artefacts from tribal belts including Sahyadri, Marai, Gondwana, Danteshwari, Bahiram and Baghdeo, displayed to the public with a self-explanatory plaque below it.

Historic photographs and objects in the museum relate to tribes from the Sahyadri and Gondwana parts of the state including the Korku, Katkari and Kolam people.

21 The women of Bhuj

A runway to victory

By Founding Fuel

On December 8, 1971, the Sabre squadron of the Pakistan Air Force dropped 14 napalm bombs on Bhuj airport, completely destroying the runway.

The Indian Air Force officers urgently needed the runway to be repaired so that flights could take off and land, to help avert the Pakistani air attacks. The Border Security Force was requisitioned for the job, but they didn’t have enough labour to get the job done.

A team of 300, mostly women, who were daily wage earners, from the nearby Madhapur village were requisitioned for the repair.

They were asked to cover the runway with cow dung so that the strip was camouflaged from enemy aircraft. Working under the supervision of Squadron Leader Vijay Karnik and his two senior officers, 50 IAF, 60 Defence Security Corps personnel, and the women toiled for three days to repair the runway. There was no real equipment and they had to work with their bare hands. There was no food available for them on the first day, till a local temple stepped in on day two with fruits and sweets.

It was a dangerous mission. Pakistani aircraft continued to pummell the area. Every time a siren would go off, the women would have to scurry and take cover in the adjoining bushes. The women wore pale green sarees to camouflage themselves. And they toiled from dawn to dusk to make full use of the daylight.

Finally, on day four, the first IAF planes were able to take off.

In recognition of their valour, the then PM Indira Gandhi offered them a group award of Rs 50,000. A Times of India report says that the women unanimously decided to use that money to build a community hall in their village.

Last year, the heroics of these 300 women was meant to be captured on celluloid with the release of Bhuj: The Pride of India on Hotstar, starring Ajay Devgn in the lead. But as is wont with Bollywood thrillers, the film makes a mockery of the actual storyline, with mindless, concocted plots that stray far away from reality. The story of the heroic women was undermined in the process.