[Image from Unsplash]

In its early, heady days, the new fintech companies believed they could overtake incumbents

In August 2016, at an event organised by TiE, a non-profit, global community of entrepreneurs, in Bangalore, right after Nandan Nilekani, former UIDAI chairman, gave his landmark “WhatsApp moment” speech (where he argued UPI will be to the payments industry what WhatsApp was to telecom), there was a heated argument between Vijay Shekhar Sharma, founder of Paytm, and Narayan Ramachandran, then the chairman of RBL Bank.

The argument was on who would make the best out of emerging technologies such as UPI—incumbents or challengers? Predictably, Sharma placed his bets on challengers. Nimble startups with superior technology talent will eat the incumbents for lunch. Ramachandran said the game was far from over, and incumbents, with their existing customer base, deep understanding of how the business works and experience in using tech, still had a chance. Most of the audience sided with Sharma.

The dominant narrative around that time was that fintech startups would increasingly capture the business of established banks and NBFCs.

As a goal, it looked tempting. Indian banking and financial services companies make a collective profit of over $50 billion. An incumbent's margin, to paraphrase Jeff Bezos, is a challenger’s opportunity.

They believed their dominance will take place through unbundling the incumbents and disrupting the industry

The path, at least in theory, looked smooth and predictable. Technology was unbundling finance like the way it unbundled traditional media companies. In the media industry, Craiglist took away classifieds, Google and Facebook took away display ads, and free websites gave compelling alternatives to print media content. A typical deck of fintech analysts featured a slide with the home page of a bank surrounded by logos of hungry startups who could potentially take away different parts of the business—loans, savings, investments, wealth management, insurance and so on. There are only two ways to make money, Netscape CEO Jim Barksdale said once: one is to bundle, and the other is to unbundle.

[Image by cbinsights.com]

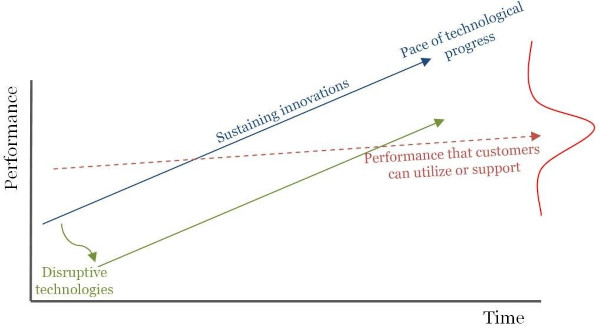

Unbundling, they argued, was only the beginning. The challengers would start with a segment that incumbents either underserved (subprime borrowers, or new-to-credit customers, or the micro, small and medium enterprises, for example) or overcharged (stock trading service), and use technology-driven efficiency to capture the market, and then climb up the value chain as described by Clayton Christensen, the guru of disruptive innovation.

[Graph of how disruptive innovation works by Clayton Christensen]

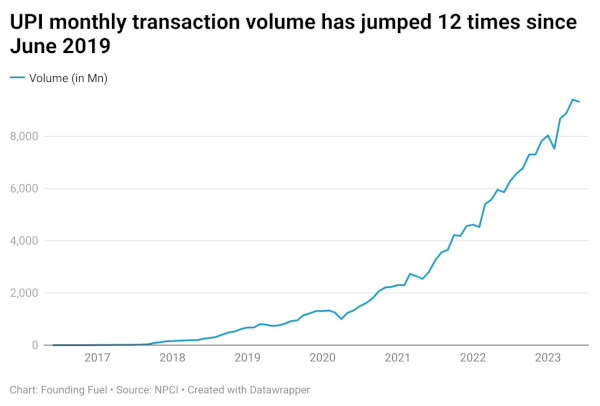

UPI did indeed transform payments, as Nilekani said it would in his speech. It scaled from a few hundred transactions a month in 2016 to over 9 billion transactions a month now. However, unlike a debit or credit card transaction, where the providers get a percentage of the transacted amount as merchant discount rate (MDR), UPI was considered a public infrastructure, and one couldn't make money out of that alone. “UPI doesn't have a business model, and it's a conversation no one was willing to have,” says Beni Chugh, who heads the Future of Finance Initiative at Dvara Research.

Instead, the conversation and the action turned to digital lending, where the real potential to earn money was. After all, humans have been getting rich through money lending for 5,000 years now. When fintech entrepreneurs said they would disrupt banks and non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), they mostly meant lending.

However, the incumbents continue to dominate the market for a number of reasons

Things didn't turn out that way. Banks were not getting unbundled, they were getting bigger. India’s public sector banks cumulatively generated profits of more than Rs 1 lakh crore last fiscal. ICICI Bank and HDFC Bank, both private banks and India’s second and third largest, outpaced Sensex in the past ten years. Some fintechs were becoming bigger too, but that came at a significant expense, especially in customer acquisition costs, often funded by the VCs. Today, many of them—especially in the consumer credit business—are stagnating and bleeding.

Fintech entrepreneurs are no longer talking about unbundling and scaling up. Instead, they are looking at ways to collaborate—either to provide technology services to established incumbents as a B2B vendor or become their partner. If you can’t fight them, join them or serve them.

The balance of power shifted in favour of incumbents because they had better business models, technology was getting commoditised and regulators favoured them.

The established players have inherent strengths: cost of capital, user base, and a distribution network

While fintech players were hoping to capture the lower end of the market ignored by the banks and scale it up, incumbents—banks, and especially NBFCs—were already expanding to the lower end of the market. This should not be surprising, partly because the government has been pushing for financial inclusion for a long time, and many NBFCs such as Shriram Transport Finance (now, Shriram Finance), a leader in commercial vehicle finance, especially pre-owned trucks, saw the potential early on in catering to segments that banks weren’t looking at.

Most importantly, banks could raise money cheaper. “It's easy to forget that banks have a phenomenal advantage in generating credit thanks to the fractional banking system. The fintech players lose out on the cost of borrowing,” says Harikesh V, executive director at Avendus Spark Institutional Equities.

Besides, incumbents could leverage their existing customer pool, whereas the fintech players faced high customer acquisition costs.

While it's tempting to think of the Indian market as 1.3 billion strong, the reality is everyone is chasing a much smaller pool of customers. “Only about 50 million have an income of over Rs 20 lakh. And about 100 million earn between Rs 3 lakh to Rs 20 lakh,” says Sahil Kini, co-founder of Setu, a fintech focussed on Open API Banking and a part of Pine Labs.

In a note earlier this year, Bessemer Venture Partners (BVP) summarised the situation saying, “Existing manufacturers in the financial services industry, i.e. banks, insurers, and asset management companies (AMCs), have a sustainable advantage on cost of capital, brand, and distribution that allows them to have a long-term edge over new tech-enabled providers.

“On the distribution side, margins are extremely low and continuously compressing due to regulatory pressures—all distributors eventually want to become manufacturers to increase margins. Moreover, in both segments, multiple players coexist without any winner-take-all dynamic,” the note added.

Incumbents are adopting technology, thanks in part to its democratisation through digital public infrastructure

Banks were always consumers of technology. Indian IT services companies such as TCS and Infosys get most of their revenues from the Banking, Financial Services and Insurance (BFSI) segment, Anand Raman, Senior Financial Sector Specialist at CGAP pointed out.

But now, banks started stepping on the accelerator, because they were realising that digitisation would make the race much harder. For example, when Arundhati Bhattacharya took over SBI, she and her top team spent a few days on an offsite absorbing insights from Microsoft and IBM and later flew to Bangalore to learn from startups there. They used that input to create a technology vision for their organisation, and a direct outcome of that exercise was the creation of a technology fund to invest in and partner with startups. Similarly, Bank of Baroda brought in Microsoft veteran Ravi Venkatesan as its chairman. Private sector banks were engaging with more startups. Yes Bank executives scoured for startups for partnership, pitching itself as one of the most technology- and technologists-friendly banks.

Meanwhile, technology was getting commoditised and easier to access. Software vendors were developing standardised, cloud-based banking software solutions that can be easily deployed and scaled across multiple institutions. This reduced the need for custom-built software and increased the availability of pre-packaged solutions. The early signs of the commoditisation was visible even in the 2000s, when Nicholas Carr published his provocative piece ‘IT Doesn’t Matter’ in Harvard Business Review. In the last ten years, it picked up steam.

In India, it manifested as digital public infrastructure—including India Stack, a set of technology building blocks that enables the government and private companies to develop and roll out various services on a digital platform.

India Stack

|

Aadhaar |

A 12-digit unique identification number issued to all Indian residents. |

|

e-KYC |

A process that allows users to verify their identity electronically. |

|

e-Sign |

A digital signature that allows users to sign documents electronically. |

|

Digi-Locker |

A cloud-based platform that allows users to store their digital documents in a secure and accessible manner. |

|

UPI |

A real-time payment system that allows users to transfer money between bank accounts without having to share their bank account details. |

|

ONDC |

Open Network for Digital Commerce, an initiative to create an open and interoperable platform for electronic commerce in India. |

|

OCEN |

Open Credit Enablement Network, an initiative to create a common platform for financial institutions to share credit information. |

On one hand, India Stack helped the incumbents to adopt technology faster. And on the other, it snatched from the startups the opportunity to build that infrastructure. As Vikram Vaidyanathan, managing director of private equity firm Matrix Partners India, put it recently, “A lot of the easy pickings on this bank tech space weren’t available here and a lot of that value was essentially captured as a public good.”

Regulators are favouring incumbents

Finally, regulators were in favour of incumbents. “RBI might not have said this explicitly, but they are clear that if you want to lend, you have to be a regulated entity. And it's not hard. One can apply for an NBFC licence or acquire an NBFC company. While it cannot guarantee that customers will never be harmed, it reduces the risk of large-scale customer harm considerably,” a person familiar with RBI's thinking through interactions over time said.

These forces were building up, and when the funding winter hit the startup ecosystem, the problems amplified. "Many fintech companies are in the initial stages of their evolution and don't have retained earnings. Their capex will have to be driven by venture investments, which are down globally,” said Mandar Kagade, principal and founder, Black Dot Public Policy Advisors.

The implications for startups are now clear. While the challengers saw the incumbents as competitors from whom they can snatch market share, they now have to look at them as more powerful partners. Some of it was forced by the RBI when it said only regulated entities can lend.

However, there are other genuine opportunities for partnership that are not dependent on regulations, but on the fundamental strengths and weaknesses of incumbents and challengers.

“There are huge gaps in technology infrastructure, especially in rural areas. This gives us, as players in this market, the opportunity to create relevant products and services,” says Sameer Mathur, CEO of FIA Technology Services that has partnered with banks for correspondent banking services in rural areas.

Technology will offer more opportunities to innovate, such as Paytm’s soundbox built for UPI transactions. “For example, credit on UPI is one of the segments where we can expect some interesting innovations,” says Setu’s Sahil Kini.

“While many assumptions that fintech players made about ten years ago turned out to be an exaggeration or plain wrong, some of the fundamental assumptions are indeed true. The most fundamental of them is that there is a credit gap in India. There is a huge opportunity to solve the problem,” said Wonderlend Hub’s Ram Ramdas. And no single entity can solve the problem. Collaboration is the way to go.

In Part 3 of this 4-part Special Report: Fintechs bet on data and algos to know the credit-worthiness of the underserved. However, there's a gap in what the data can reveal because of consumer behaviour.

Read all 4 parts here.