[Photo by Faustin Tuyambaze on Unsplash]

Forgive, O Lord, my little jokes on Thee

And I’ll forgive Thy great big one on me.

- Robert Frost

There is an urgent need to rethink the curriculum of all education. An increasing lack of trust in business institutions, the demand for more accountability for environmental and societal sustainability, and the rapid changes in technologies, shapes of industries and the content of work, is especially compelling schools of business, management, and development studies, to go back to the drawing board. This essay proposes that all schools should prepare their students to be better life-long learners and to be better citizens. It recommends that disciplines of deep listening and systems thinking must be included as foundations in an educational curriculum that teaches students how to learn.

VUCA has become a trendy managerial acronym: VUCA is short for volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. ‘The only constant is change’, one is reminded frequently. What has changed though is the pace of change and the pattern of change: it is more dynamic, faster, and less predictable. Another trendy word in business and policy circles is ‘innovation’. Like salt that must be added to most dishes, it seems that innovation must be mentioned in all management presentations. VUCA and innovation go hand-in-hand. The more the world changes, the greater the need for innovation. And, the greater the number of innovations, the more the world changes! Anything may happen: predictions cannot be made in an IVI (Innovation- VUCA-Innovation) world. Managers are expected to meet targets certainly and get things done efficiently. Therefore, the IVI world presents an existential challenge to the very concept of ‘managing’.

Management schools must predict the knowledge and skills their graduates will require in the future

Teachers of management, and managers of management schools, have an even deeper challenge. Unlike educational institutions whose only purpose may be to prepare young people to be good citizens (of which there may be hardly any left anywhere), management schools are expected to prepare people to earn money and create wealth. Therefore, they must predict the knowledge and skills their graduates will require in the future and they must design their institutions to provide these requirements efficiently. Thus, they are caught in a double bind. Their students cannot know what skills and knowledge they will need in the future in an unpredictable IVI world; and management schools cannot know precisely what to teach them that will remain useful!

In an IVI world, human beings must be life-long learners. The separation of life’s course between a period of intense education followed by a period of applying what was learned and reaping its benefits can no longer be sharp. The only useful knowledge without a short shelf-life will be the ability to be a good learner throughout one’s life. Therefore, management schools especially (and other providers of vocational knowledge too—in medicine, law, engineering, etc.) must develop their students to become better learners. Students must learn to learn, and teachers must go back to school to learn to learn too!

Learning to Learn

Data analysis

The anxiety to understand what is going on, and to get hold of the ‘facts’, is spurring the growth of Big Data and data analytics, assisted by an explosion in availability of data with the proliferation of applications of digital technology.

Systems thinking

In an IVI world, more data alone cannot help to make sense of what is happening in the world. Disparate phenomena are colliding: passions with reason; nature with man-made infrastructure; democracy with autocracy; a need for stability with a need for change. Disparate phenomena, some of which are not easy to digitise and quantify, must find their places in a mental model, and their relationships understood, to understand what is going on and why. This is leading to an emerging interest in the disciplines of systems thinking.

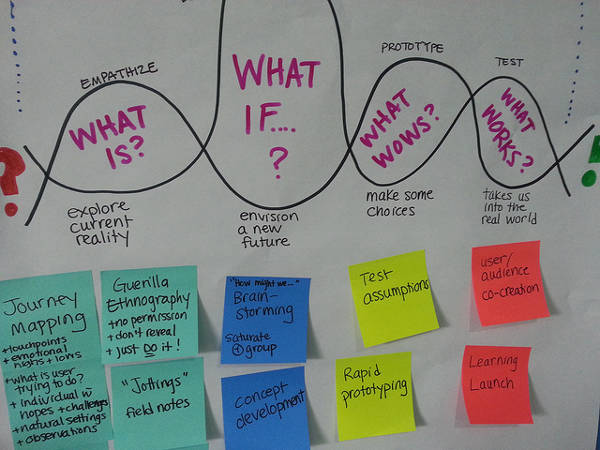

Design thinking

The nature of the human enterprise is to endeavour to improve the world, and not merely to understand it. This urge has led to the development of new technologies, and innovations in designs of institutions too. In an IVI world, the ability to systematically design good products and services that fit emerging societal and consumer needs has become very valuable. The concept of methodical design seems attractive for the design of institutions too.

Listening and dialogue

Design of trustworthy institutions requires a greater ability to listen to stakeholders’ concerns and aspirations

Design to fit emerging needs requires an understanding of what those needs are. Therefore, an essential requirement for good designing in an IVI world is the ability to listen deeply to people in the world around the designer, and to notice things for which there may not be enough data yet. Whereas new products and services may satisfy emerging ‘consumer’ needs, new forms of institutions will be required to fulfil emerging ‘citizen’ needs for more trustworthy institutions for businesses, better governance of societies, and more harmony in the world. Hence it is tempting to apply the ideas of systematic ‘design’ to the design of institutions too. The design of trustworthy institutions requires an even greater ability to listen to the concerns and aspirations of stakeholders. While designing products and services, a designer, after exploring needs, may choose to focus on attractive segments to serve, putting aside those whose needs are not easy or profitable to fulfil. Whereas designers of institutions that will be trustworthy must address the needs of those not easy to satisfy. The designer must overcome her own difficulties in listening to their needs too.

A critical difference between products and services on one hand, and institutions on the other (especially governance institutions), is that products and services can be provided by producers to consumers, whereas social institutions work when all stakeholders work together, with none as an outsider of the ‘institution’ providing the ‘institution’ to others. Therefore, institutional design requires stakeholders to listen to each other in a dialogue, and not only the designer listening deeply to potential customers.

Ethics

Several international surveys, such as the Edelman Trust Barometer, have reported that trust in institutions of business and government has declined greatly in recent decades. Many instances of poor governance and unethical conduct have come to light in many, previously admired companies. High performance of a business is not good enough, citizens say. Therefore, business schools are being compelled to include the teaching of ethics with their menus of management skills.

An MIT professor’s jest of the process of education in a classroom is: ‘Education is a process of information going from the notes of a professor to the notes of a student, without going through the minds of either!’ Ethics, teachers say, is a virtue, which cannot be taught in a classroom. Howard Gardner, Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, recommends, in his book, Truth, Beauty, and Goodness Reframed: Educating for the Virtues in the Twenty-First Century, that ethical principles are learnable through a process of inward reflection by students. He recommends that students maintain notebooks in which they record their questions and their reflections whenever they encounter beauty or an ethical dilemma. (Thus, the notes in these books will be their own inward reflections, not a transmission of information about ethics from the notes of their teachers!) Gardner says that virtues, like beauty and ethics are learned, not taught.

Gardner says that morality and ethics are virtues associated with the performance of one’s roles in society. Making a subtle distinction, he suggests that moral principles, such as do not lie or do not steal, apply in one’s roles in a family or community. They are the grist of religious commandments. Whereas more abstract ethical principles apply to a person’s professional responsibilities in a society, such as the ethical responsibilities of doctors, lawyers, and business managers. The distinction between them is not as important as the description of both, morality and ethics, as an exercise of personal responsibility in relationships with others and with society.

Levels of listening

Ethics is learned by listening to one’s inner voice and building an internal set of guidelines. If designing a good product or service requires a designer to listen deeply to another; and co-designing of institutions requires people to listen deeply to one another, developing ethical virtues requires listening deeply to oneself.

The Observer and the System

[From Pixabay]

Progressing from objective data analytics to designing products, then to shaping institutions, and finally onto developing one’s internal ethical compass in relationships with others, the observer moves from being detached from the system being observed (and designed) to becoming an integral part within the system and messily connected within it.

The change in orientation necessary, from being an ‘engineer’ designing a product or service to accepting that one can be only a humble component within the system—as much affected by the system as one can affect it—can be painful. Robert Frost’s short poem at the opening of this essay alludes to this pain.

The creation myth is that man (and man more than woman) has been created in God’s image. This idea has created a hubris in man that he can, and must control everything, including nature and women too. However, as he develops his abilities to control nature further, nature reacts. The evidences of rapid depletion of natural resources and climate change are warnings to man that he has gone too far with his scientific innovations exploiting nature to serve his greed for material progress. Who is the controller? Nature or man? Man’s little jokes on God are now being replied by God’s big joke on man.

Even the attempt of a human being to take control of himself or herself is a joke, Frost’s poem may suggest. Who is the ‘I’ within the human mind that controls the thoughts in the mind? Descartes said, “I think therefore I am”. In other words, it is only because I have thoughts that I know I exist. My thoughts and I cannot be separated. My thoughts are me and I am my thoughts. At this depth of learning, ‘I’ become when I learn about my relationship with the world: about how my thoughts and actions affect the world, and how the world affects my thoughts and actions.

Thus the ‘I’ in ‘IVI’ is not just innovation that is encompassed in the evolution of the world. ‘I’ too am an integer within the world: affecting it with my little jokes; and being affected by its jokes on me.

Systems’ Archetypes

I now present two contrasting archetypes of systems distinguished by (1) the scope of the system and (2) the relationship of the designer to the system. One is a ‘bounded-engineered’ system; the other an ‘open-evolutionary’ system.

In a bounded-engineered system, the designer is outside the system that he designs. Moreover, the contents of the system are mentally restricted to what can be rationally understood by the designer. Whereas in an open-evolutionary system, the designer is a part of the system whose design is evolving. The designer is evolving too, emotionally and spiritually.

The contrasting properties of these systems’ archetypes can be seen in the clash of two fundamental laws of science, one which applies in engineering, and the other in evolutionary biology. The Second Law of Thermodynamics, which every engineer knows well says that the entropy in a system (that is the disorderliness within it, and dissipation of useful energy within it) will inevitably increase over time. In contrast, the law of evolutionary biology says that complex systems will inevitably evolve over time, producing organisms with greater capabilities. Both laws are empirically proven. Though contradictory, both are correct, because they describe two different types of systems.

What it is to ‘know’ is different in the two systems. How one ‘learns’ is also different. Bounded-engineered systems privilege rational intelligence. Learning in an open-evolutionary system requires combinations of multiple intelligences—rational, emotional, and spiritual.

What is designed, and how it is designed, is also different. In a bounded-engineered system, the design is a ‘machine’. The ‘machine’ could be a physical product or service capability. The concept of machine also includes the design of software and algorithms to manipulate data to produce results the designer wants. In an open-evolutionary system, the designer also evolves along with the evolution of the designs of institutions and systems, and the designer may humbly learn about ‘who’ he really is—a small part of a large creation, and not the powerful creator that he imagines himself to be.

Action-Learning: The Learning Cycle

[By Christine Prefontaine under Creative Commons]

So far, I have opened up the concepts of knowledge and learning, from data and analytics, and rational/logical learning, to a broader view of learning encompassing other forms of knowledge and other ways of knowing. Now I will put these ideas together into a ‘learning to learn’ framework. Central to this framework is the concept of action-learning: of learning so that one can improve one’s actions and acting so that one can improve one’s learning.

‘Sense and respond’ may be the most basic way to describe the process of action of insects, animals, and even chemical substances. They sense something in the environment and respond to it. It is also an elementary description of the process of learning. A child learns about the world by poking at things and observing their reactions. However, a child’s mind begins to go further. She wonders why the object reacted the way it did. She may try to open up the object. Or, she will experiment by changing the way she pokes the object to see what then happens. Thus, a very basic representation of a learning cycle consists of four steps—sense, respond, observe, and then adjust response (SROA)—repeated iteratively. It is similar to the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) learning cycle. With each cycle, knowledge is improved, and the action sharpened too.

Though seemingly similar, there are two significant differences between SROA and PDCA. PDCA does not seem to give a prominent place to ‘sensing’ before planning. The other difference is in the splitting of the response step in SROA into two steps—plan and do—in PCDA.

The emerging discipline of design thinking often describe a three-step process of insighting, creating, and prototyping. The first step, corresponding with sensing in SROA, requires a designer to immerse herself, with an open mind, in the real world of potential customers. From this open-minded exploration fresh insights may emerge. Then, in the next step, creative responses may be conceived to these insights. After which, physical prototypes must be produced to make the ideas tangible and testable. This corresponds to check in PDCA. The fourth step in both SROA and PDCA, of systematically acting on the insights obtained from the trial actions, though emphasised in design thinking, is not explicitly stated in the three-step design thinking framework.

Combining the best of these three learning frameworks, I use a learning cycle with the following four steps:

- Sensing/insighting

- Creating/visioning

- Prototyping/experimenting

- Reviewing/adjusting

The fourth step feeds back into the first step to complete the iterative learning cycle.

We can now position the various learning disciplines—design thinking, systems thinking, listening and dialogue, ethics, etc.—in this framework, as well as compare the concepts and tools provided for each step.

Sensing/insighting

Both design thinking and systems thinking give great importance to the first step. Design thinkers are urged to immerse themselves in the real world of potential customers, without pre-conceived notions, to sense unmet needs. Systems thinkers are also urged to see the world through many diverse perspectives and only then to put together a view of the system.

Both design thinking and systems thinking require deep ‘listening’ without prejudice in the first stage. The difference at the sensing stage between the two may be in the scope of the system being explored and therefore the diversity of the people to be listened to. The recent surge of interest in design thinking has arisen from the business sector, where there is interest in developing new products and services for customers. Therefore, the exploration will be focused on a smaller set of potential customers and stakeholders than in systems thinking explorations into broader societal issues.

The more significant difference is the application of systems mapping tools in systems thinking. The toolkit of systems thinking has tools to analyse and to visually present the connections between diverse forces in the system. Application of systems thinking tools in design thinking will improve the quality of insights.

Systems thinkers use the image of an iceberg, most of whose mass is below the water line, to explain the power of systems thinking. They say that conventional approaches to data gathering gather information about what is visible above the water line. Whereas, deeper forces, of emotions, prejudices, and biases, that make people do what they do and think what they think, are not visible. They can be explored only by going beneath the water line into others’ perspectives, which requires deep listening.

Dialogic processes enable very deep insights into the forces causing conflicts in societies

Dialogic processes are built on the discipline of very deep listening. They enable people to understand the points-of-view of people they do not agree with and who they do not like to meet. Dialogic processes enable very deep insights into the forces causing conflicts in societies. Dialogic processes can enable people to understand their own biases and observe the mental filters they unconsciously apply which limit their understanding of others. Dialogic processes are tools for very deep learning about the world. They can provide insights also into who ‘I’ am.

Creating/visioning

The next stage of designing is to produce an innovative idea to meet the unmet needs sensed in the first step.

Robert M. Pirsig poses a fundamental question in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. Writers are taught rules of good writing. But that is not sufficient to produce a great essay or book. The beauty of a great essay lies not only in the quality of the writing itself. Even more, it is in the idea the writer is expressing. But where does the idea spring from, Pirsig asks? Creative (or innovative) ideas seem to arise magically, in creative flashes. Once the idea is there, it can be given a good shape—with the skills of good writing if it is a book, or the skills of the mechanic if it is a machine.

Creative ideas are more likely to emerge when the analytic left brain is stilled. ‘Sleep over it’, is good advice when the mind is struggling with a complicated problem for which a solution is not clear. Many techniques have been developed to suspend left brain thinking temporarily, marketed by creativity labs and consultants. They are designed to make the mind temporarily ‘unlearn’, by shaking the mind out of its habits, to clear mental space for fresh ideas.

In product design processes, the new idea may be visualised in the mind of an individual designer. Whereas in processes of social change, where many, diverse actors have to shape the future together, the new idea must be a shared vision. Therefore, visioning must be a collaborative process while designing social change with new institutional arrangements. The process of listening remains important in this step in institutional design processes. Stakeholders must listen to what other stakeholders care about to create a shared, aspirational vision to guide the next steps to take together to bring about the desired change.

Prototyping/experimenting

‘Out of little acorns, big oaks grow.’

A new idea when it forms may seem attractive in the mind. However, it is fuzzy, and needs to be fleshed out so that it can be seen better. When it can be seen more completely and concretely, one can also test it and evaluate how it might work in the real world. The building of prototypes and experimenting with them is an essential part of processes of design and innovation. If the idea is the seed, the sapling that grows out of it is the prototype. One can now visualise a tree.

‘Give the sapling a chance to build strength before you start pulling at it to see how strong it is’, is a rule recommended to designers and innovators. One can imagine many reasons why a new idea will fail. There is an anxiety to check too soon if it will work and is worthy of being invested in further. When the idea begins to take shape (the sapling appears), it behoves the entire team to concentrate on how to make it work rather than evaluate why it will not work. In other words, strengthen the idea before you put it to test.

Product and service ideas can be prototyped to test more easily than can ideas for institutional changes. Nevertheless, prototyping is essential in processes of societal innovations also before they are rolled out on a larger scale.

Major improvements have been made to processes of designing complex physical products such as automobiles and airplanes with application of computer-aided design and testing. The need for physical prototypes is greatly reduced. The prototype can be visualised on a computer screen, and it can be manipulated and subjected to digital tests. And the design can be altered and significantly improved before a physical product is made in almost its final, ready to roll out form.

The equivalent in the social world of prototypes in the physical world are ‘scenarios’. Scenarios are descriptions of what shape the system can take if certain forces in it prevail. They are sketches of what the world could become, not predictions of the future. Scenario thinking (which is an outcome of systems thinking) works with shape scenarios, rather than range scenarios that economic and business forecasters use. Range scenarios describe the consequences of different levels of a critical variable—such as oil prices, or GDP growth. Whereas shape scenarios describe alternative shapes the system can take with combinations of various forces. Range scenarios presume that the structure of the system will remain basically unchanged. Whereas shape scenarios, which are formed from an analysis of the structure of the system, can project fundamentally altered conditions of the system.

Scenarios formed from systems thinking provide wind-tunnels through which ‘what-if’ ideas about particular forces can be mentally tested. Thus, scenarios derived from systems thinking are a powerful tool for prototyping and experimenting when designing social and institutional change.

Reviewing/adjusting

The fourth and last step in the learning cycle feeds back to the first step. It is a very critical step, and a very difficult one too. At this stage, the strength or weaknesses of an idea is revealed, and its success and failure can be judged. However, not only the idea is judged, people who promoted the idea feel judged too.

The US Army instituted the practice of ‘After Action Reviews’ in the 1990s as part of its programme to become a faster and better ‘learning organisation’. After any significant military action, the leader and the participants were required to sit down and reflect about what they could learn. Some suggested questions were:

- What had we set out to accomplish?

- What have we actually achieved?

- What did we think we knew about the environment when we made our plan?

- What do we know about the environment now?

- What has contributed to the gap (if any) between what we set out to do and what has been achieved?

The purpose of these broad questions was to stimulate a blame free introspection about why the variation, and not who was to blame for it.

In the second chapter of the Bhagavad Gita, Sri Krishna advises Arjuna: “You only have a right to the work, and not to the fruit thereof.” In other words, success or failure of a project should not trouble the doers.

In practice it is very hard to avoid feeling blamed for failure even if no blame is ascribed, or to avoid wanting appreciation for success. Participants find it hard to avoid insinuating blame or avoid crediting individuals for the success. Emotions are always present. Rules for conducting good dialogues can help to manage these undercurrents and improve the effectiveness of after action reviews.

Theologian Reinhold Niebuhr noted a prayer: “God give me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; the courage to change the things I can; and the wisdom to know the difference.” (It has been reported that this prayer was found on a slab in a small church in rural England.) Well conducted after action reviews, in which one’s ego is stilled, can be sources of wisdom too.

Going Deeper and Broader

While journeying through the steps in the learning cycle, the disciplines of systems thinking and deep listening and dialogue enable travel at deeper levels.

Design thinking

Design thinking, applied to design of new products and services, is often taught without teaching concepts and tools of systems thinking. It can work quite well in the realms of customers and products and services, with the designer sitting outside the system, providing a solution to it. Nevertheless, design thinking for products and services would be enriched with the addition of disciplines of systems thinking and deep listening (and dialogue).

Systems thinking

Systems thinking and deep listening (and dialogue) are essential for change in social systems and environmental systems, and for changing embedded institutional arrangements. Whereas industrial design systems work in the realms of customers and products and services, social and environmental systems operate in the realms of citizens and institutional arrangements.

Both, product (and service) systems, and societal and environmental systems, operate in a ‘market’ of exchanges, of give-and-take. Markets for products and services, in the customer-and-business realm, operate in realms of things that money can buy. Citizen-and-society systems must operate in markets for needs that money cannot buy, where fairness and equity, and justice and dignity are values whose increase is the outcome desired, not only monetarily measurable values of financial profit, shareholder wealth, and GDP of nations.

Intangible values such as dignity, justice, and harmony, are not easy to quantify—and perhaps lose their essence when dried into quantities. Yet they must be included in an analysis of the forces that shape the world. Improvement of the quality of these values must be a principal objective of design of social systems and institutions. Systems thinking and ‘shape’ scenarios enable the inclusion of such unquantifiable and yet essential forces in models of the system. Systems’ scenarios are not constrained by the language of quantities. They can be presented evocatively in powerful pictures and stories.

Deep listening and dialogue

The purpose of such a deep dialogue is to provide participants with a space to understand the world and themselves

Design thinking is in the upper layer of the learning cycle. Systems thinking is deeper. Even further down, beneath systems thinking, are dialogue and meditation. David Bohm says, in On Dialogue, that the purpose of a deep dialogue is not to find a solution to anything. Indeed, he says, participants should enter into a dialogue without any common question in mind. Open-minded dialogue may lead each of them to internal questions, and perhaps the group may converge onto a shared question. However, the purpose of such a deep dialogue is to provide participants with a space to understand the world and themselves, which they are unable to when they seem to be always under pressure, in their professional and domestic lives, to manage and solve problems.

It is very difficult, amidst our lives’ routines, to find the mental and emotional spaces in which one can experience the Gita’s wisdom: “it is only the work and not the result that matters.” Or to find times and spaces in which one can merely observe one’s thoughts without the instinctual urge to improve something or oneself. These are the times and spaces that practices of meditation are designed to create for us. Thus, deep dialogue, in Bohm’s view, is a collective meditation to understand and learn, and not to achieve anything.

Aldous Huxley explains in The Perennial Philosophy, how the spiritual traditions within all religions—Hinduism, Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Sikhism, Taoism, and other faiths—are a search for ‘the peace that passeth all understanding’. The search leads to insights about what and who ‘I’ am, and also to why ‘I’ am in the world. Insights into why I am here can lead on to an understanding of what is ethical conduct.

Designing an Education Curriculum

[From Pixabay]

All the King’s horses and all the King’s men could not put Humpty-Dumpty together again.

Redesign of the educational curriculum has become necessary to prepare students better for the 21st century ‘I(V)I’ world, in which change has become very fast and unpredictable, and when several ethical issues of equity in society and sustainability of the natural environment must be urgently addressed. Schools of business and management must provide learning of ethics and also incorporate issues of sustainability in their curriculums. At the same time, with industries and skills changing very fast, and with questions about the ‘future of work’ itself (which is the subject of a two-year-long research project coinciding with the International Labour Organization’s centenary), the shelf-life of the knowledge provided to the students in vocational schools (which include schools of management, business, and social development) is reducing.

When the principal purpose of a good education in a short dose of a few months or years should be to teach a student how to learn throughout her life, what should be crammed into that time? This itself is a design problem: what should be put into the container and how should the contents in it be arranged?

Some ideas are suggested here for redesigning the curriculum.

Foundational disciplines

Systems thinking and deep listening/dialogue are essential, ‘cannot-do-without’ disciplines for learning to learn, especially in a dynamically changing world. They must be included in a 21st century ‘learning to learn’ curriculum.

The European Age of Enlightenment since the 18th century ushered in scientific thinking. Subjects began to be divided into specialties, each knowing more and more about less and less of the whole. The epistemic approach to knowledge was: one must know each component better to understand the whole. In practice, specialists got to know more and more about less and less. The wisdom that comes from understanding the whole, and how each part fits in it (including the place of human beings in the universe) began to get lost.

Most of the difficult, global challenges confronting the world in the 21st century, such as those listed in the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, are systemic problems. Solutions to these problems require multi-disciplinary approaches and collaboration among diverse stakeholders.

The approach to knowledge of systems thinking is fundamentally different to the dominant approach of scientific inquiry. Systems thinkers focus on the properties of systems rather than on more knowledge of their components. When components come together, the system acquires unique capabilities which cannot be foreseen merely by knowing the properties of all the components. The systems’ properties arise from the connections among the components. Therefore, the concepts and tools of systems thinking look at the properties systems have because of the arrangements of the components within them. Indeed, the more the pursuit of specialisations in the physical and social sciences, the greater is the need to put their knowledge together again (like the fallen Humpty Dumpty).

The Dalai Lama has written in his foreword to my book, Listening for Well-Being: Conversations with People Not Like Us: “Listening is the first of the three wisdom tools in Buddhist tradition, the other two being contemplating and meditating; it is the gateway to improving oneself, both mentally and physically.” He also recommends, “I believe that the notion and practice of dialogue can and should be taught to students in schools, just as we teach them to appreciate democracy. We can train students to debate different views. In this way, the concepts of dialogue and resolving conflict non-violently will be instilled in them.”

Listening is a foundational requirement for learning. Listening with genuine interest, and with a desire to learn, to other, seemingly wrong and strange points-of-view, opens windows into new knowledge and insights. It can lead to more social harmony too, which is urgently required in a world being ‘broken into fragments by narrow domestic (and ideological) walls’, as Tagore had feared. Social media, by enabling everyone to connect, is perversely forcing people into conceptually and ideologically gated communities, across whose walls they hurl abuse at others and through which they cannot listen to each other. The disciplines of deep listening and dialogue are essential for good design thinking and systems thinking as explained before. They are also necessary to make students better citizens of a globalised world.

Systems thinking and deep listening should be included as foundational disciplines in all educational curriculums.

Learning through action

Habits of the mind (and ethics) cannot be changed by lectures. As Howard Gardner recommends (ibid), deep-seated ‘lenses’ in the mind through which truth, beauty, and goodness are apprehended, can be softened and reformed only by becoming aware of them in practice. Therefore, the educational curriculum must include more periods of observation of the ‘real world’. These encounters, could be through ‘learning journeys’. These journeys could be through rich case studies, or through field visits to see real things and in encounters with real people in real places. Learning journeys can provide raw material for students to practice their skills of deep listening and dialogue and systems thinking.

Students can be taught the basic concepts of systems thinking and deep listening before they embark on their learning journeys. During which they can apply them. And, afterwards, in an ‘after action learning’ together, they can have a deeper dialogue among themselves. What did each of them see and hear? How come some noticed some things which others did not? What are the lenses and filters in our minds? How can we map all the things we have found to be important, and the questions we now have, into a shared view of the system? What are the insights we have from this systems’ view?

What should we have more of, and what less of

Curriculum design will be constrained by the time available to the school with the student. The addition of new foundational disciplines and more time for learning journeys and group work will require that the time allocated for something else in the present curriculum should be reduced. What will this be? Or, how can the other subjects be taught more effectively in less time—perhaps by taking advantage of the inclusion of the new foundational disciplines into the pedagogy? Can overlaps among courses be reduced? Can courses be combined?

There cannot be a cookie-cutter, ‘one size fits all’ design solution for all schools. Every school has its history, and therefore its inertia to change—especially if it is an established and successful school. Moreover, schools have different focuses: for example, management and business, social studies, development studies, sustainability, etc. Therefore, they must include the ‘technical’ subjects that provide domain knowledge in their fields. It is essential to include such subjects. Some questions are: How much time should be given to them, and which ones? How should they be taught to improve students’ abilities to become better life-long learners?

Finally, can our schools and universities become better, continuously learning schools and universities themselves, rather than being merely efficient teaching factories producing students to fit the job market as it is presently rather than preparing good life-long learners?