[Image by Werner Moser from Pixabay]

India is on the glide path to emerging as one of the economic powerhouses of the world. Its economy is ranked sixth in size globally (and slated to climb to second largest by 2030); it has the fastest growing annual GDP growth rate among (major) countries; the country ranked in the world’s top 10 destinations for foreign direct investment in 2017-18. With a population of 1.3 billion and a large middle class of more than 300 million, it is one of the most attractive markets globally. Specifically in the digital economy, India has a huge IT industry with a market size of $167 billion; it boasts of a 55% market share in global IT services and outsourcing; 1,140 global corporations run their tech R&D centres in India. In the tech startup space, India has attracted private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) investments of $33 billion in 2018, and it has over a dozen unicorns (startups with a valuation of over $1 billion).

These data-points are truly impressive and would make any country proud. And yet, one of the glaring historical paradoxes of the Indian economic story is the sheer absence of world-beating products from India.

Ask Indians to name three truly world class, globally loved Indian products or brands and chances are they’ll struggle to name even one. Check out the Global Innovation Index 2018 from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). India doesn’t figure in the top 50 countries. Or the Interbrand 2018 Top 100 Global Brands Ranking. There’s no Indian name on that list.

The Indian IT and digital sector doesn’t fare any better than the bricks-and-mortar industries on this count. IT services, which is the lion’s share of this sector, comprises largely of low-end, commoditised services or cost-arbitrage-based outsourcing contracts. Most of the new age tech unicorns in India are based on ideas and business models that are copied from foreign innovators (with some local tweaks). Their outsized valuations are a result of them being the gatekeepers to the large Indian market, rather than from having created path-breaking products from first principles. So, the overall trend is that India has a large domestic market, and it is a big supplier of technical brain power on the world stage, but when it comes to building innovative products, we come a total cropper. This is best reflected in Infosys co-founder NR Narayana Murthy’s candid quote: “There has not been a single invention from India in the last 60 years that became a household name globally, nor any idea that led to earth-shaking invention to delight global citizens.”

Launch of the National Policy on Software Products

It is in this light that the recently rolled out National Policy on Software Products (#NPSP) by the ministry of electronics and IT (MeitY) marks a watershed moment. For the very first time, India has officially recognised the fact that software products (as a category) are distinct from software services and need separate treatment. The Indian tech sector was so dominated by outsourcing and IT services, that “products” never got the attention they deserve. As a result, that industry never blossomed and was relegated to a tertiary role. Remember that quote “What can’t be measured, can’t be improved; and what can’t be defined, can’t be measured.” The software products policy is in many ways a recognition of this gaping chasm and marks the state’s stated intent to correct the same by defining, measuring and improving the product ecosystem. Its rollout is the culmination of a long period of public discussions and deliberations where the government engaged with industry stakeholders, Indian companies, multinationals, startups, and trade bodies to forge it out.

#NPSP will bring into focus the needs of the software products industry and become a catalyst in the formulation of projects, initiatives, and policy measures aimed at Indian product companies. One of its starting points is the creation of a national products registry that’s based on a schematic classification system. Other early initiatives that will help in operationalising the policy include setting up of a software products mission at MeitY, dedicated incubators and accelerators for product startups, development of product focused industrial clusters, preferential procurement by government from product companies, programmes for upskilling and talent development etc.

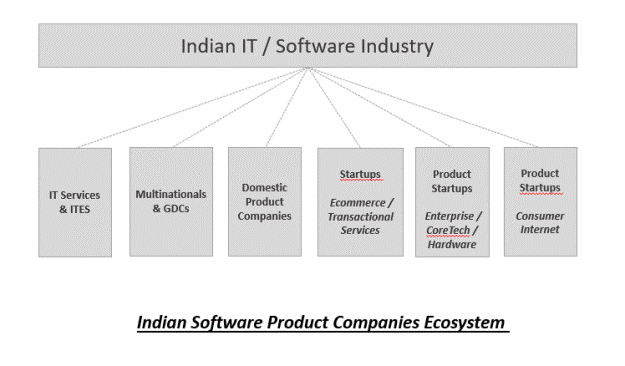

The Indian IT and Software Industry Landscape

To understand the product ecosystem, one needs to explode the $167 billion Indian IT / software sector into its constituent buckets. The broad operative segments that emerge are:

1. IT Services and ITES: This is by far the largest bucket and dominates everything else. Think large, mid- and small-sized services companies throughout the country servicing both domestic and foreign markets—such as TCS, Infosys, Mindtree, Accenture, and GE.

2. Multinationals / global development centres: These are foreign software companies serving Indian markets and/or using India as a global R&D development centre—such as Microsoft, Google, Netapps, McAfee, and IBM.

3. Domestic product companies: This is a relatively small segment of Indian software product companies selling in domestic or overseas markets—such as Quickheal and Tally.

4. Startups (ecommerce and transactional services): This is the large, fast-growing segment of startups in the area of direct (or aggregated) transactional businesses like ecommerce, local commerce, grocery shopping, food delivery, ride sharing, and travel—examples include BigBasket, Flipkart, Amazon, Grofers, Milkbasket, Swiggy, Dunzo, Uber, Ola, Yulu, Ixigo, and MakeMyTrip. You could also include the payment and fintech companies in this bucket—such as Paytm, Mobikwik, PhonePe, PolicyBazaar, and Bankbazaar. This segment has absorbed the maximum PE and VC investments and is poised to become bigger with time.

5. Product startups (enterprise / core tech / hardware): This comprises companies like Inmobi, Zoho, Wingify, Freshdesk, Chargebee, Capillary, electric vehicle startups, and drone startups. They could be serving Indian or foreign business-to-business (B2B) markets.

6. Product startups (consumer internet): This segment includes media/news companies, content companies, social and professional networking, entertainment, and gaming—such as Dailyhunt, Inshorts, Sharechat, Gaana, Spotify, YouTube, video/photo sharing apps, and Dream11.

(Note: Of course, this segmentation schema is not water-tight and there could be other ways to slice and label it.)

Why India Lags Behind in Software Products

The global software products industry has a market size of $413 billion. It is dominated by American and European companies. India’s share in that pie is minuscule—India is a net importer of $7 billion worth of software products (It exports software products worth $2.3 billion; imports worth $10 billion). “Software is eating the world”—entire industry segments are being re-imagined and transformed using latest developments in cloud computing, artificial intelligence, Big Data, machine learning, etc. In this scenario, it is worth understanding why India seems to have missed the software products bus. The reasons are multifarious, cutting across cultural, economic, market, behavioural and societal factors.

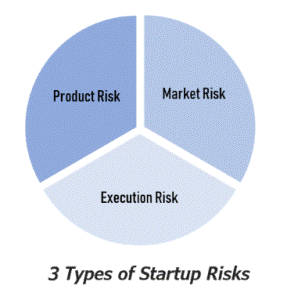

1. Cultural aversion to risk, ambiguity and failure: Indian society has traditionally valued conformity and prepares people not to fail. Our family and educational environments are geared for teaching us to eschew risk-taking and avoid ambiguity. But building products is all about managing risk and failure. When you take a product to market from scratch, you take on multiple types of risk—market risk, execution risk, product risk. For many in India, this is in stark contrast to their social and attitudinal skills and the expectancies they have built up over a lifetime.

2. “Arbitrage” offers the path of least resistance: If you pour water over a heap of freshly dug mud, it will find the path of least resistance and flow along it. Human behaviour is similar. It is conditioned to look for the path of least resistance. And “arbitrage” offers that in the IT industry—be it cost arbitrage, labour arbitrage, geographical arbitrage, or concept arbitrage.

The IT services industry leverages the cost arbitrage model via cheaper labour costs. Many of the transactional ecommerce startups in India have used geographical arbitrage to their advantage—once a successful product or model is created in another market, they bring it to India to capitalise on a local first mover advantage, build a large valuation and become the gatekeeper to the market before the (original) foreign innovators arrive in India many years later! But arbitrage means, that while you are taking on market and execution risk, you are not assuming the product risk. That dynamics played out at scale over the years—so, it is easier for a wannabe entrepreneur in India to go the arbitrage way and quickly build out a business using a readymade template, than go down the software products path, which has a much longer gestation and higher risks associated with it.

This “arbitrage” factor represents the single biggest reason why India has seen a virtual explosion in ecommerce startups, at the expense of product startups. Look around the startup ecosystem and you’ll see all kinds of transactional businesses involving activities like buying, selling, and trading. This reminds me of that famous 17th century quote by Napoleon when he described Britain as a “nation of shopkeepers”.

3. Tech isn’t enough—you need design and marketing skills: To build great software products, you not only need strong technical abilities, but also good design, marketing and branding skills to carve out a compelling product offering. Ask any startup in India, one of their most common problems is the inability to hire good designers and user experience professionals. This puts Indian companies at a comparative disadvantage—even if they have the engineers to build the technology, their inability to translate that technology into an appealing user experience often means the difference between success and failure.

4. Lack of “patient” venture capital: This is a complaint you hear often from Indian product startups—the lack of venture capital that’s willing to be patient over the longer gestation cycles software products demand. While there is some truth to it, the more likely explanation is that software product companies present a chicken-and-egg problem for Indian startup investors. Investors are driven by financial returns. If they see returns from product companies, they’ll bet their monies on them. It just so happens, that Indian investors haven’t yet seen venture-sized returns from software product companies. Hopefully this dynamics will even out as the ecosystem grows.

5. Inadequate domestic market potential: Many software products are monetised via subscription models, where the market’s ability (and propensity) to explicitly pay for the service is critical for success. Sometimes (SAAS/enterprise) companies try their model in India, only to discover there just aren’t enough paying customers. These startups may then be left with no choice but to either target foreign markets, or in extreme cases just move abroad for business continuity. Thus it has become imperative for the Indian domestic market to grow in size and scale to ensure product startups are viable.

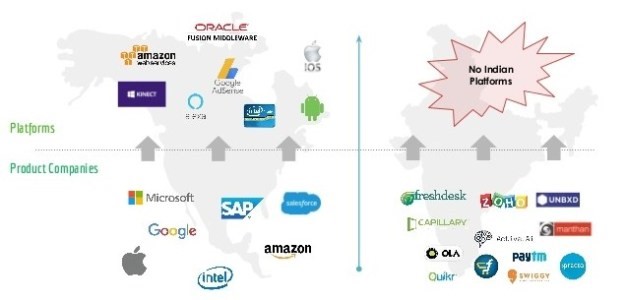

6. Platform companies from India are a non-starter: I am calling out one aspect specifically: the sheer absence of any platform companies from India. Platforms are the next evolutionary step for scaled software product companies. If you get to the stage where other industry stakeholders start building on top of the plumbing you’ve provided (thereby becoming totally dependent on you), that’s an immensely powerful position to be in—like with AWS, Android and iOS. This factor assumes even greater importance given upcoming trends in artificial intelligence, machine learning, deep learning, automation, and robotics. The companies which emerge as platform providers may offer strategic advantages to the country of their origin. As depicted by the graphic below, India is as yet a non-starter on this count.

This is deeply worrying. Imagine a scenario 10-15 years out, when Indian software companies start dominating the domestic markets and also are a force to reckon with globally, but it’s all built on intellectual property (IP) and platforms created and owned by foreign companies!

Some Suggested Action Areas for the National Software Policy

MeitY in consultation with industry stakeholders is likely to create an implementation roadmap for #NPSP. Here are some specific action points I’d like to call out for inclusion in that roadmap:

Develop the domestic market: As explained earlier, the Indian domestic market needs curated development to reach a potential that makes product startups viable without having to depend on overseas markets. This calls for a series of steps, such as policy support from sectoral regulators, funding support via special go-to-market focused venture capital funds, etc. The government could also help by announcing a preferential procurement policy from domestic software product companies. The Government e Marketplace (GeM) can help in institutionalising these procurement norms.

Catch ’em young (create early awareness): Fed by constant news in media about IT services, ITES, BPOs, and outsourcing, the average person in India is likely to be aware of IT services, but not necessarily software products. Many people may have friends and family members who work at firms like TCS, Infosys, Wipro, and IBM. But the same can’t be said about product companies. Given this scenario, it is important to create early awareness about products in schools, colleges, and universities across metros, and Tier 1, Tier 2 and Tier 3 towns.

Some of the world’s biggest product innovators like Bill Gates and Steve Jobs started writing software before they had reached high school. If we can catch people young, we actually get a much longer runway to get them initiated into the product ecosystem. If they learn about products after they’ve started working in the industry, or when planning a mid-career shift from services to products, it might be quite late.

Reduce entry barriers for starting a software product company: Like I mentioned earlier, one of big problems in the Indian software product space is that there just aren’t enough entrepreneurs starting up product businesses. Ecommerce and transactional services actually absorb (or suck in) a lot of entrepreneurial talent by virtue of having lower barriers to entry. To make a serious dent in products, you need a much larger number of product companies started off the ground. This can happen only by systematically bringing down the entry barriers—driving awareness, providing funding support, providing market development support and so on. Advocacy and evangelism by software product industry role models also can help develop confidence and conviction in people to think products instead of services or ecommerce.

Build domestic software product companies atop public goods: Silicon Valley has shown how you can build successful commercial applications on top of public goods (for example, Uber built on top of GPS, Googlemaps and mobiles). In a similar way, public goods in India like India Stack or National Health Stack (NHS) can be the base (or the plumbing) over which commercial applications get built for mass scalability. (India Stack is a bunch of tech platforms—the national payment platform (UPI), eKYC, DigiLocker, etc. NHS is a similar digital infrastructure comprising an electronic system for beneficiaries, doctors, hospitals, and insurance companies, that is being built for the Ayushman Bharat scheme.)

The good news is, this trend has already been kick-started, though it is still early days.

(This is a slightly modified version of an article first published on webyantra.com)

Also Read

Paul Allen the artist versus Bill Gates the entrepreneur