I first met P.G. Mathai sometime in early 1994. I was a young reporter at Businessworld (BW) and had just been transferred to Bombay from Calcutta. He had joined BW in Delhi as Executive Editor, and was visiting Bombay around the time I was shifting. We were at the same hotel, The Westend, in Bombay’s Marine Lines, and as he wanted to see me, there I was, knocking on his door with some trepidation as he was a super boss.

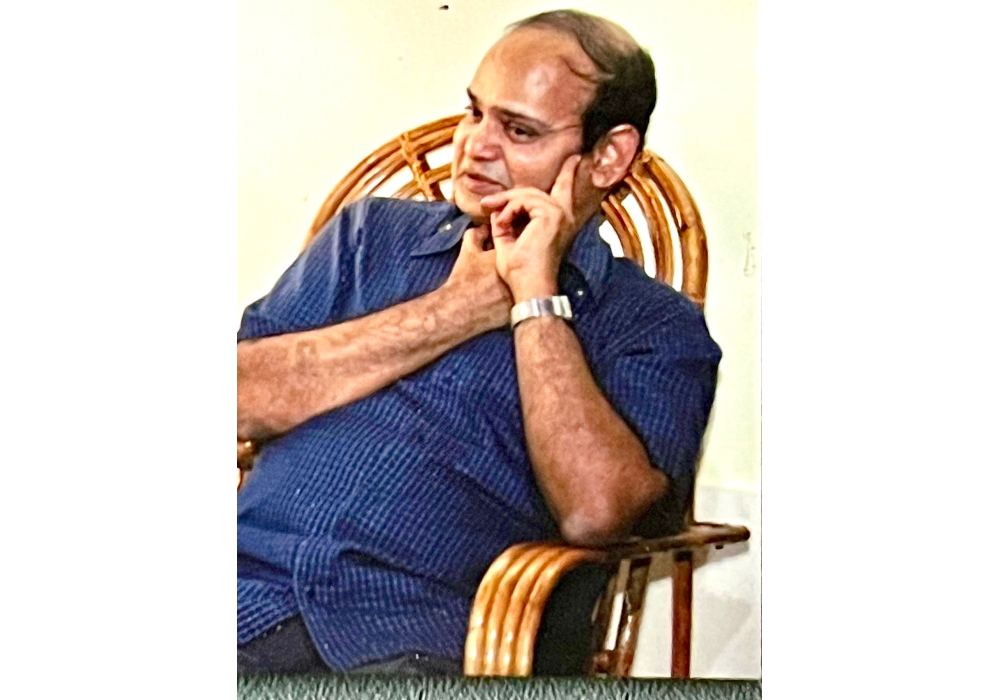

A balding man with a baby face and a deep, newsreader voice opened the door. He was dressed in a half-sleeve ‘bush’ shirt and a lungi; on the table behind was a half-consumed bowl of ice cream. Somewhat embarrassed that he had been caught mid-dessert, that deep, newsreader voice said: “I say, do you want some ice cream?”

“I say.” That was Palakunnathu George Mathai. Most of us used to call him ‘Mr Mathai’, though I don’t quite know why. And he had much to say.

Mathai came from a generation of journalists who treated journalism, especially in the written word, as the highest form of craft. Their careers had begun in the late 1960s or in the early 1970s when there was no television to speak of and print ruled supreme. Decades later, when my generation of writers began entering newsrooms, print still ruled supreme.

Newspapers, and particularly magazines employed masses of rewriters and subeditors who brought a horologist’s attention to detail to ensure that sentences, insights, and the narrative synchronised perfectly. They worked in the background, rarely got a byline, but wielded immense power, for, without their sign-off, no article could ever be published. It was very common for articles to be held back for weeks and sometimes months as the rewriters practised their magic. They were perfectionists all, and Mathai their undisputed prince.

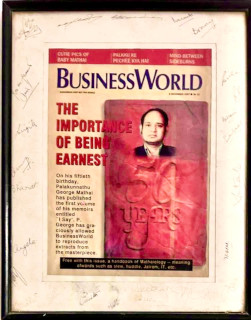

He would call you into his room and start the sentence with, “I say,”. And thus would begin a masterclass on how to write an article. It ranged from explaining the difference between ‘few’ (not too many) and ‘a few’ (some) to how to make the first paragraph more gripping. (In 1997, when we wanted to gift Mathai something special some months after his fiftieth birthday, we made a mock-up of a BW cover page, which carried the story of Mathai’s fictitious autobiography called, ‘I Say’.)

[The mock-up of the BW cover, to mark Mathai's 50th birthday]

What made him doubly knowledgeable (or dangerous to a young journalist, depending on your point of view) was he used to occasionally report himself and could therefore see through the laziness of other reporters. A typical Mathai sentence would go like this: “I say, the story needs more legwork.” ‘Legwork’ was his go-to phrase; what he meant was that the reporter hadn’t met enough people before writing the story, what the Americans call ‘shoe-leather reporting’, and would need to go out into the field again.

He practised the art of gentle admonishment. In the eight-odd years I worked with him never once did I hear him raise his voice at shoddy work. He was no smoke-spewing editor from hell, but rather an avuncular figure who knew he had much to contribute but did so softly, though firmly. There was a standard Mathai mannerism at moments like this: while commenting on the article, he would caress his own face in long, vertical strokes from his cheeks all the way down to his chin with his left forefinger and thumb. He also had the habit of remembering his days at the India Today desk, where I think he had worked sometime in the 1980s. If I remember correctly, India Today then had some of the best writers, rewriters and editors in the business, people like T.N. Ninan, Suman Dubey, Dilip Bobb, Paran Balakrishnan, and Jagannath Dubashi.

We all knew when Mathai had worked on our copy. It came peppered with words like ‘slew’ or ‘whopping’. If the copy needed important voices, they would typically come from R.C. Bhargava of Maruti or Subodh Bhargava of Eicher Motors or for that matter Jairam Ramesh, especially if the piece had anything to do with the economy. But the finished product would leave us astonished.

Mathai’s writing skills had been recognised early on. As his father was in the foreign service, Mathai spent parts of his youth abroad. In New York, he met Francis Newton Souza, the artist. They became pals and Souza asked Mathai to ghost-write his autobiography. Mathai wrote a few chapters and then dropped the project. A sketch of Mathai’s by Souza remains.

[The sketch by FN Souza]

Every summer Mathai would go off on a month’s leave. He would lock his room and pocket the key. One summer, in the late 1990s, we decided to play a prank. Unbeknownst to him, the office guard did have a spare key. The morning Mathai was to return, his secretary, Seetalakshmi, who was in on the plot, convinced the guard to open Mathai’s room and one of us plotters switched the air conditioning on.

Mathai returned buoyant after his vacation, beaming ear to ear. He opened his door and was surprised that the air-conditioner was on. Seetalakshmi casually let it slip that the machine had run continuously while he was away, and since he had the only room key, nobody could switch it off. And oh, the admin folks in Delhi had reported this to their counterparts in Calcutta (BW was those days a part of the ABP Group) as a matter of procedure. Mathai shrugged it off; none of it registered.

The next day, we wrote a very official sounding letter (“Dear Mathai; It has come to our knowledge…”) took a printout on thermal paper to make it look real (that was the era of faxes) and got Seetalakshmi to hand it over to Mathai. The ‘fax’, from ABP HQ, said that a substantial sum of money, down to a decimal number (ABP accountants were always very precise), would be deducted from his salary to pay for the much higher air conditioning bill.

Mathai was thunderstruck. He called Bidyut Chatterjee, the head of editorial services in Calcutta who played along as he was in on the prank. As did Mathai’s boss, the then managing editor of BW, P. Swami. They both said that it was very difficult to overlook the error especially given how senior Mathai was. Any leniency would reek of favouritism. Of course, if a junior employee had done something similar, the organisation might have shown some leniency because after all, no company is that cruel.

By sheer stroke of luck, the ‘fine’ and his latest credit card bill also reflected similar amounts; and now he was not sure how he would pay for both. The prank played out over a few days, after which we came clean. Mathai had a good laugh, and complimented us on our ability to pull off a prank like that. He also said such effort and meticulous thinking should go into the articles we wrote.

I can’t think of too many bosses who would be so kind.

I had my last few interactions with Mathai over WhatsApp in early May. He was gravely ill, could barely speak, and knew he was dying. Yet his messages were upbeat and didn’t reflect his condition. And as expected, his sentences were well crafted—brief, and with the right descriptor he conveyed what he wanted to say.

He died on 12 May, leaving behind many whose lives he touched by his sheer decency and whose journalism he improved. We all owe a collective debt of gratitude to Mr Mathai, who gently pushed us to do better.

That, I will say.

D.N. ‘Bonny’ Mukerjea worked with P.G. Mathai for eight-odd years.