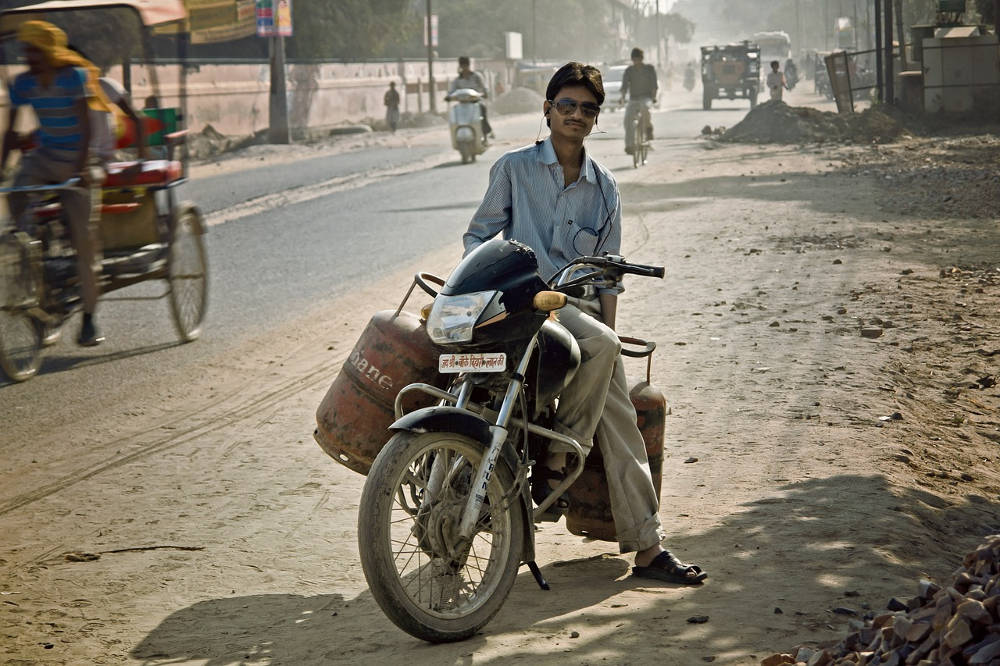

[Photograph by Tumisu under Creative Commons]

As I begin to write this, it is December 31, 2016. I just got back from an early morning walk along the beach and the lanes and by-lanes of Fort Kochi in Kerala. And as I sit down to write this essay, a few answers to questions that have been playing on my mind for a few months, are now reasonably clear to me.

- India may have just lost to China. We had on hand an opportunity to build a model of entrepreneurship that can be called uniquely Indian.

- When realisation dawns and reactions like bans of any kind are imposed by policy makers, it backfires. This includes demonetisation around which, until now, I have maintained silence.

- And even as this happens, the world is getting disrupted. India is hopelessly underprepared for what lies ahead.

I hope to god I am wrong.

It is pertinent you ask me why do I say this? Most of what I believe in now is built on the back of conversations with multiple sets of people, listening in to differing views, and poring over data.

God’s Own Country

In my mind, some pointers to what could possibly have been an Indian model of entrepreneurship have emerged on the back of my many walks through the streets of Fort Kochi. Home to my ancestors, this is known to the world outside—and that includes me—as a state rooted in communism. I am for all practical purposes an outsider—in my head and to everyone else. A “Bombay-boy” is what everyone calls me.

Indeed. My home is Mumbai. To that extent, all of what I see here is as witnessed by an outsider. And my morning walks are not driven by health, but desperation to get myself a packet of cigarettes that I inevitably run out of in the nights.

Unlike every other place in India where cigarettes can be purchased from any corner store, it isn’t possible here anymore. Not because cigarettes are technically banned, but because over time, policy makers have mounted a concerted effort against tobacco. It first started as a ban on smoking in all public places. “Do not vitiate the environment you are in with foul air” was the public stance policy makers took. Nobody could argue against it.

Over time, the courts were moved to ban vending cigarettes near schools, places of worship, tourist spots, and so on. Nobody could argue against that either. Who, after all, wants their children corrupted, their places of worship polluted, or the air around them smell filthy? Offenders are liable to be penalised by the police. Sure, you can hawk your wares wherever you choose to. But if you smoke in a non-smoking zone, you stand the risk of being prosecuted. Over time, demand plummeted.

Most vendors now think it is not worth their effort to stock cigarettes. They’ve stayed put at the same places, but sell other products that offer higher margins. And where cigarettes are available, they are sold at a premium.

As for smokers, it isn’t worth taking a rickshaw and going around the city on a cigarette hunt. And when you do find one, the chances of finding the brand you smoke are slim. Whatever is available comes at a premium. Quite honestly, it isn’t worth the effort.

In much the same way, a clinical battle is being waged against alcohol. There is no prohibition in place. But the rules are such that only the scum would go through the pain to stand in long queues to procure a bottle of alcohol. At high-end restaurants and bars, taxes on spirits are high. To make establishment costs viable that they may be able to serve alcohol, only beers, wines and prohibitively priced spirits are available.

I could not help but notice the cost of living is high here as well compared with what it is back home in Mumbai. Consider labour for instance. It is both expensive and difficult to come by than in other parts of the country. More interesting still, the forces that fill this population are immigrants from other parts of the country like Odisha, West Bengal, Bihar and North East India—all of whom converse in fluent Malayalam. They won’t work anyplace else because they earn twice what they would earn in any other part of the country—including Mumbai where I hail from.

Prince Thomas, my friend and former colleague, had highlighted the nuances and paradoxes of it all in a dispatch from 2014 in the Indian edition of Forbes magazine.

So, where are the locals and what are they doing? I must confess to feeling like a country bumpkin here. Over time, on the back of many social and economic variables, they are far better off than people like me who live in the so-called land of opportunity.

For lack of a better phrase, a unique model of entrepreneurship has evolved. Prince had alluded to this as well way back in 2012 when he wrote about two local brands of umbrellas known only to Malayalees—Johns and Popy. “Marketing gurus will tell you that only in Kerala have umbrellas made the transition from a commodity to a product,” he had then written.

For various reasons though, most people know Kerala in terms of the now clichéd line sold to tourists—God’s own Country. But how horribly wrong that perception is!

This isn’t a cheap place to visit. You need to be part of the moneyed. And monies the local population possess in any case. To vacation, they’d much rather visit Sri Lanka, Singapore, or some other destination in South East Asia. The more moneyed choose even more exotic locations.

Just that I may add some more perspective to how this state has evolved, consider my neighbour Ramesh Menon and his wife Kalpana. They operate Dal Roti, a hugely popular restaurant in this part of the city. It serves North Indian food and is much sought after for the kathi rolls.

A white American couple was waiting for their turn to be seated. First come, first served. But in Menon’s scheme of things, it was past the mandated closing time and a lot many people had to be turned away—including the American couple. “Bloody Brown mother*&#&…,” the man muttered under his breath. “This isn’t how you treat tourists who bring dollars.” In any other part of the world (or perhaps in any other part of India, I suspect) he would have gotten away.

But Menon pounced. “How did you dare you say that?” he screamed. The motley crowd assembled there didn’t quite know what to do as Menon held the man by the scruff of his collar and went in to call the police “for insulting local sentiments”.

“I don’t need your bloody dollars,” he yelled. By then the couple figured they were in trouble and pleaded to be let off. The people here, entrepreneurs, and law makers don’t take kindly to insults. They are a proud lot. More pleading and some intervention from those who knew him later, Menon let them go. “It’s New Year’s Eve. So, this once, I’ll let it pass,” he said.

“I earn enough money off our citizens who spend more per table,” he told me later over a mug of chai that we share every morning when I am there.

On an altogether different note, when I hire a taxi, I like to engage in conversations with the drivers. Including those of Uber. I was curious to understand how they are doing in Kerala. I had punted taxi aggregation platforms like this will storm this bastion. In my experience, hiring taxis here was ridiculously expensive, inconvenient and the operators whimsical. They had to be put in their place. Who better than an aggregator like Uber?

I was horribly wrong. In all my conversations the taxi drivers, or Uber partners as the platform calls them, sounded despondent. Uber hadn’t taken off the way it thought it would.

Auto rickshaw drivers I spoke to didn’t sound worried. It wasn’t Uber’s entry that had hit them. It was the ban on currency that had gotten their goat. A lot many of them were trying to install digital wallets like Paytm that business may ply as usual.

What I found interesting is that there’s an emerging model unique to Kerala. All drivers affiliated to various trade unions have converged. They are now experimenting with a platform and an app to compete with aggregators like Uber and Ola. Unlike in other parts of the country, all voices to drive these entities out have faded. Instead, the premise is, why ban a good party? “Learn and join in” seems to be the refrain.

This is not to suggest all is well here. There are multiple issues to be dealt with. A hydra headed monster like rampant drug abuse is one such that policy makers must deal with. But that is not my point.

It was time I asked myself: What did I read wrong? As an outsider looking at the microcosm that is Kerala, which exists in India, a few thoughts crossed my mind:

- If Kerala, ostensibly a communist bastion and perceived as all things anti-capitalist can morph, what impedes other parts of the country?

- The Americans created the American way of doing business. The Chinese created theirs. What is the Indian way? In fact, is there an Indian way of doing business?

- Did Indian policy makers look closely at models like Kerala’s to figure if answers exist in the long term?

- Nothing is banned here. Not tobacco. Not alcohol. No moral police patrol the streets. The ones that do are subject to derision. Everything is available. Just that the policies are designed such that what the people and state have agreed upon as undesirable are difficult to come by.

- It didn’t happen overnight. No policies were implemented surreptitiously. People are literate and informed. Much debate follows every proposal. What gets implemented often meets with resistance. But when implemented, it is done well.

When looked at from this perspective, why did the central government have to demonetise high denomination notes? Would I be off the mark if I suggested India lost its nerve when it needed to hold it most? The consensus view from both within and outside is that India lost the plot, the GDP its steam, and entrepreneurship stands to be hit.

My submission is this: Those who live in Lutyens’ Delhi lost sight of where the many, and very real India’s live.

The Real Indias

Until not too long ago, I looked at India as a homogeneous mass—a population of 1.2 billion people exploding at the seams. After China, it was clearly the largest market in the world and was there for the taking.

Two people challenged that perception. The deputy Prime Minister of Singapore T Shanmugaratnam and Haresh Chawla, a partner at Indian Value Fund and contributor to Founding Fuel. The former argued that there’s no reason for India to celebrate growth at 7-8%. The latter produced evidence that India is living on a dream and a bubble.

[Photograph by Devanath under Creative Commons]

Earlier in 2016 when Shanmugaratnam addressed Indian parliamentarians in an eloquent and provocative speech, he raised a few interesting questions.

- What is this obsession with “Make in India”? Why not obsess with “Make in India for the World”?

- In an increasingly insular world, ought not a country of India’s size and potential take the lead and open up her borders? Why ought India not lead Asia and the world? Why should China dictate terms?

- As for 7-8% growth, is it worth gloating over? Because, the trained economist argued, when looked at coldly, “It will get India to 7-10% of China’s income in 20 years.” Bluntly put, this isn’t good enough. “It is a luxury India cannot afford.”

To that extent, his prescription was, the onus lies on Indian policy makers and entrepreneurs to think long-term and disrupt. By way of example, he spoke of how Singapore pulled itself out of the boondocks it was in a few decades ago. It was hard work and took time.

Indian policy makers, on the other hand, were lulled into complacency by growth demonstrated in the Indian IT services sector. They extrapolated that growth as a proxy for all of what was possible for India. But they were barking up the wrong tree. Because IT services is a fickle business. It follows the cheapest dollar.

The Wall Street Journal reports once upon a time, Wipro “used to send a team of 100 employees to write, install and provide support for clients’ accounting software. Wipro now does such projects with eight people.”

The report quotes TK Kurien, now the executive vice chairman at the company, as saying that 40% of Wipro’s workforce does not have the skills they need for cloud computing—a skill they are scrambling to infuse their software engineers with.

Another report from the Wall Street Journal quotes chief executives of various Indian IT firms as saying the ways in which services are delivered to various customers need to be reimagined and that a bloodbath is imminent. Even as recently as five years ago, nobody had imagined this future possible.

Then there is another much-overlooked fact. Every school of thought saw India as a homogeneous entity of 1.2 billion people. It was a market waiting to be captured. But nobody had looked under the hood.

Haresh explained the nuances in a powerful and widely circulated piece published on Founding Fuel. “Simply put, we live in three countries,” he wrote and called these countries India One, India Two and India Three.

India One: “….The top 15% of Indians, i.e. about 150-180 million, earning an average of Rs 30,000 per month, are the ones who have money left over after buying necessities. They control over half the spending power of the economy and almost its entire discretionary spending.”

Indian Two: “This is the middle 30% or 400-odd million Indians, earning an average of Rs 7,000 a month. This would be a country about three times the size of Bangladesh. They ‘service’ the $1 trillion market India One represents.…Most of their income is spent on food and rent…They buy second-hand smartphones and tiny sub-one-hundred-rupee data packs to keep in touch. Of course, we report them as internet consumers in our slick presentations on Startup India.”

India Three: “These are the forgotten 650 million who subsist and don’t have the money to buy two square meals. Their incomes rival that of sub-Saharan Africa. They are the ones who did not leave our road-less, school-less, toilet-less, and power-less villages and instead chose to send a child or a sibling to work in the big cities.”

“Net, net we are three countries. One with the size and wealth of a developed nation, another of 400 million people like a developing nation, and a third, the size of a continent with 650 million people whose lives rival that of a poor nation,” Haresh wrote.

When thought of deeply, people like me who write stories like this one, those of you who read them and our policy makers live in India One. And we are the ones, like the Deputy PM of Singapore pointed out, who have celebrated dramatic growth when we ought to be working harder.

An Indian in the World

Into the many nuances that comprise India as articulated by Haresh and the questions raised by Shanmugaratnam, add the uncharted territories the world is moving into. I will not dwell on Trump and Brexit—much has been said, written and debated around these themes. I’ll focus on just one disruptive force that’s gaining traction among many others—Artificial Intelligence.

Over the years on the back of various experiments, companies like the ubiquitous Google have learnt way too much about you and me. All this, on the back of inputs that come from the tools and ecosystem it built for us. So much so, it has now begun experimenting with driverless cars that can drive me around. Uber wants to do the same. Build cars that can take you from Point A to Point B on the back of all the data it collects via the app that resides on our phones and tracks all of what we do.

Driverless cars are only the beginning of AI. The battle is for dominance of the phone that resides in your pocket. Any entity that has the most number of insights about who you and I are, and what is it we really do, will be the biggest gainer.

If you think this too far into the future, consider this. When you get on board a transcontinental flight to take you 10,000 miles across the ocean, technology exists to do it minus any humans. But it is psychologically reassuring to passengers that they hear the crackling voice of somebody who describes himself as “captain”.

After a flight takes off, charge is handed over to automated systems. Those in the cockpit have nothing to do. They take over only when it is time to land. But even that is unnecessary. It is proven that take offs and landings are safer when handled by automated systems. Our minds aren’t willing to buy into this reality yet. So, airline pilots have a job.

Step outside the airlines business and look at the financial markets. Last year, the 25 best paid hedge fund managers took home $13 billion with the top two taking home $1.7 billion each. Incidentally, the best paid banker was Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan Chase, who earned $27 million. What explains this disparity?

“The hedge fund model is under challenge,” said the billionaire investment guru Leon Cooperman. “It is under assault.” And he isn’t sure anymore whether or not he ought to keep his funds open. He was among those who lost money for his investors in the year. So much so, the guru didn’t figure in the list of Top 25. And of those who did gain, more than half used algorithms to beat the markets. So much so, investors are asking why bet on humans at all and pay hefty fees when risks are as high? Why not let algorithms make the decisions?

As they get more sophisticated, it’s fast approaching a tipping point. In Hong Kong for instance, a private equity firm called Deep Blue Ventures has actually inducted an algorithm as a director on its board. The regulatory authorities are still to come to terms with the issues on hand.

Take it one step further outside the boardroom and it gets into the realm of robotics. Japan’s Softbank now has one called Pepper. As NS Ramnath noted in an essay on Founding Fuel: “It can effectively replace some of the boring work that sales people do (and do some other activities better than humans). This characteristic places Pepper at a stage where we are more likely to accept robots among us—let machines do the boring stuff, so we can focus on the more interesting and more important stuff.”

I won’t go any deeper into what is possible. But these forces are knocking at our doors.

A young man whom I’ve seen from close quarters knows only one job—to build precision tools. His wife is in the travel business. They have twin girls. But they cannot afford to buy a home.

Bonds though run strong in the family. The older brother has done well and is in the financial services business. He funded a mortgage so this younger couple may buy a new home. But he is now worried because he can see desks around him emptying out as jobs are either moving to other lower cost Asian economies or being automated.

He is concerned about what AI is doing at his headquarters in the US. His family though remains unaware of what he is up against. He knows it is only a matter of time before headwinds come his way. What, he often wonders, will happen to his jobs? What happens to the mortgage he helped fund? What happens to his future and that of his brother? How will he pick up the pieces and reinvent? These are real questions he and I discuss often.

Now multiply this across scenarios using the metrics Haresh presented and think about the question Shanmugaratnam raised: Are you happy growing at 8-10%? Is it an option?

Pain is Inevitable

I finally find myself a packet of cheap cigarettes. And the subtleties of Haresh’s arguments begin to sink in. I can afford to be out at this time of the day to hunt for a packet of cigarettes because I am part of “India One”.

That said, I see the other subtleties he was alluding to as well. Most of my relatives who live here are well off. They have greater discretionary spending power than I do. But they do not see the point in paying for a fancy organic breakfast when they grow it in their backyards. How is an entrepreneur to deal with an animal like this?

While this creature has the discretionary spending power, it is unwilling to spend and lives like anybody who is part of India Two in a metropolitan city. This creature moves seamlessly between India One and Two.

This is a uniquely Indian problem. American business models were built in an America context. They are based on an idea called velocity. Move fast, spend crazy amounts of money, capture markets, and rule. It worked well for American companies in the past. Which is what Uber is all about. Indians are in love with this and have tried to emulate it. But this model is under significant stress.

The most recent set of numbers from Uber, that poster child of Silicon Valley, has got alarm bells ringing in some circuits. The company currently runs up over $2 billion in operating losses each year—more than that of any start up in history.

Ben Thompson who pointed me to this in a post on Stratechery (behind paywall) summed it up:

“…Uber is a fundamentally unprofitable enterprise…Uber’s ability to capture customers and drivers from incumbent operators is entirely due to predatory competition funded by massive investor subsidies—Uber passengers were only paying 41% of the costs of their trips, while competitors needed to charge passengers 100% of actual costs.”

But the Americans are cognizant of it and haven’t stopped innovating. On the contrary, they are trying very hard. If you were to look up MIT’s 2016 list of the 50 smartest companies, Google and Uber don’t make the cut. Amazon is the world’s smartest company. And there are others that make the cut, many of whom are powered by AI and are in the life sciences field.

The Chinese were cognizant of their realities. They made their mistakes. But over time, a Chinese model of entrepreneurship has evolved to create the formidable flotilla that is unique to the country.

How many people outside China know much of Baidu? It follows Amazon on MIT’s Technology Review list as the World’s second smartest company. It is China’s leading search engine, is developing autonomous cars backed by big research and has an engineering team in Silicon Valley. Didi and Alibaba from China make it to the list at 21 and 23, respectively.

It begs a question. Why are there no Indian entities on the list? Why are there no Indian models of entrepreneurship that people talk of? A version that did the rounds for a while was around a theme called jugaad, first popularised by CK Prahalad. But jugaad does not insist on innovation. It suggests “make do with what you have.” It doesn’t work in the long run. Prof. Rishikesha T Krishnan, director at IIM Indore, has repeatedly made this point on why, both in his book on the theme and on Founding Fuel.

[Photograph by Freeimages9 under Creative Commons]

What were we doing in India then? I don’t have any insider knowledge. But basis all of what I see and on the back of many conversations, I suspect some concerned people in policy making circles have seen the writing on the wall. They got spooked and may have argued that some radical triggers must be pulled if India is to make a dash to the post. Demonetisation was perhaps one such. But did it have to be like this?

If even flimsy evidence be needed, consider some demands Apple is placing to “Make in India”. Why is the Indian government bending backwards to accommodate a company that is now floundering? Do we really need to make in India (read manufacture) in the literal sense?

Why not “Innovate in India”? Ought India not have learnt its lessons after having witnessed first-hand what happened to the poster child IT services sector? When there is a text book case like Kerala waiting to be studied, why are our policy makers looking elsewhere?

The ground beneath India’s feet has shifted. Pain is inevitable.